Lingering on from the relational aesthetics craze in the '90s, works labeled “community art” and “social practice art” run the risk of getting bad reputations today. An artist’s effort to interact with communities can be seen as ephemeral interventions that homogenize the term “community” as a group separate from their own distanced position. Communal-based projects moreover have lost their radical desire to break beyond the White Cube’s walls as museum “community-project” commissions become more prevalent. But artists like Theaster Gates are challenging the presumed negativity of an artist’s capacity to truly collapse the boundary between art and life, proving how art’s transformative desire can have a lasting effect and critical edge.

Trained as an urban planner and potter, Gates transforms the “raw material of urban neighborhoods into radically re-imagined vessels of opportunity for the community.” Known best for his renovations of soon-to-be-foreclosed buildings in Chicago into libraries or galleries (such as the “Black Cinema House,” “ Archive House” or “Dorchester Art and Housing Collaborative” ), Gates funnels the proceeds of each new collaboratively-built structure back to finance the rehabilitation of entire city blocks. In this excerpt from Phaidon’s monograph Theaster Gates , Columbia art professor Carol Becker talks with Gates on how he evades the negative connotations that follow terms like “community art” and imagines an artistic practice with a lasting impact in real social and urban structures.

Theaster Gates's Chicago studio with a formal gallery and woodshop.

Theaster Gates's Chicago studio with a formal gallery and woodshop.

Carol Becker: Your work is receiving a terrific response from many sectors of the art world. Do you think this is related to the end of postmodernism and how genuinely weary we’ve become of taking the world apart?

Theaster Gates : It seems some of us are trying to put things back together. The reason why art is important is because it doesn’t have to represent anything, and it could point to something much bigger than painting, or to something much more complicated than the detritus that’s on the ground. Projects that are successful are symbolic. You’re looking at something that’s really trying to represent something else. I can make a symbolic gesture, but there are times when the symbolic gesture, like 2,500 Ugandan women are all wearing white head garbs to protest against war, can have real consequences, real effects, such as men being released form prison, or a new policy being made around the need for anti-rape laws in Rwanda.

Symbolic gestures and performative gestures can lead to real change

Yes. Not that they always have to, but there’s a way in which artists might have the power to conjure the symbolic, to do things in the world that other folks couldn’t imagine.

Let’s imagine that the South Side of Chicago could be different. A preacher might imagine the South Side being different by saying, “I could grow my church and we could maybe get some housing for our parishioners and then making things better.” That’s good and practical. Or there’s the mayor, who says, “These are the tools that I have as mayor.” Or the police, who say, “Well if we had more police, we could help reduce violence.” All good, but, actually, we need a greater symbolic act than any of these instrumental acts could ever offer. But few people are imagining the great symbolic acts.

So that’s where you and other artists come in: using your ability to create images and symbolic reality that people can respond to.

There’s nothing special about rehabbing a building. But then to call it something like the “Archive House” and to make a small residential building public—that does something. I’m talking about reaching the places where other kinds of power and capital and collateral come from. If you have an art career that’s doing pretty well, some of the folk who are taste-makers and change-makers in say, Chicago, come to this symbolic place, and they’re like “Well, this is cool.” They talk about it. They talk about it with Power, and they say, “Hey, Power, there’s this symbolic act that’s starting to happen,” and then this one little building becomes two little buildings, and those buildings go out into the world. I talk about the buildings over and over again for a year. I go to Detroit; I go to St Louis; I go to Omaha; I go to Gary, Indiana; I go to Philadelphia, and they’re like, “What are you doing?” I’m thinking about these processes where, if I embed myself in a place and get to know the people around me, and we have these shared values, cool things can happen. The by-product of that embedding is what we call Dorchester Projects. But Dorchester Projects is also a by-product.

Stoney Island Arts Bank before....

Stoney Island Arts Bank before....

Stoney Island Arts Bank after renovation.

Stoney Island Arts Bank after renovation.

That wasn’t the project?

That’s what I’m saying. Dorchester could be anything. We need to focus on how we make that thing beautiful, contextual, symbolic. I can’t make Dorchester again anywhere else. If I’m somewhere else, I have to think: “What’s around me? Who’s doing what? Who are the people that I know? What are the skill sets?”

When you go to Omaha, St. Louis or Detroit, you’re not ‘embedded,’ as you are in Chicago. How does that work? You project a big vision that helps propel you and others forward. Are the people on the ground in these cities then able to sustain the necessary determination to pull off these projects once you’re no longer there?

I offer really tangible ways of supporting large, sometimes symbolic acts. The folk I’m engaged with rarely need my help; they need new ways of looking at problems about which they’re all-too familiar. A painter makes a painting; the painting goes to somebody’s house; the painting means something to the new owner; and maybe it gains value. The more value it gains, the more precious it becomes and the more people tend to care for the painting. People want the painting to be seen in a museum; they ship it a certain way; they get professionals. There’s a way in which this painting still feels like an extension of an artistic practices.

I wouldn’t even say extension. It is an artistic practice.

I go to Omaha, and they say to me, “What kind of art do you want to make?” I say, “I want to have this town-hall meeting, and I want to talk to some folk before I can tell you what I want to make.” I find out that there are thirty black artists in North Omaha, who have been applying for the Bemis Residency Program and have never gotten in. I’m like, “The Bemis Center for Contemporary Art will never accept you because you didn’t go to grad school. Your aesthetic is very different from what they’re interested in, and there might be a little but of a cultural mash-up that they’re not sure they know what to do with. Why don’t we build a space over here that’s about the things you believe in, that can cater to you?” Before I know it, the town-hall meeting turns into a conversation with the department of planning and the mayor. They give us a small building. We trick it out, and then that building becomes the Carver Bank —a space for black artists in North Omaha. Does it need to be all black? No, not really. In a year, we were able to raise money, build out the site and get a programmer. It got to the point where the Carver Bank seemed to be doing so well that Bemis was like, “Oh, we want this. We want to keep this.” And so, that was the artwork, which took two years. In addition, and at the same time, I was trying to get a small sandwich shop to move into the space, trying to get a program up where this residency could be ongoing, trying to figure out where money could come from long-term. That happens to be the set of raw skills that I have as a creative person.

And I would say it’s also a methodology.

It’s a methodology. One part of it is the constant question of, how do you sustain it? But before I get to how do you sustain it, I ask, “Why does a painting need to exist at all? Why the gesture? Why would we do mark-making if mark-making is meaningless?” I can’t start at “Is the Carver Bank sustainable?” What I care about is that the black people in North Omaha know that they can approach the department of planning, they can approach the mayor, they can develop a plan, and they can activate abandoned space in their neighborhood. That’s the important part. I think we focus too much on the effect—the finished work—and not enough on the methodology or process.

That’s because the object has value.

It’s because the object has value!

And it’s because people don’t know how to quantify process.

The part that gives me courage, or that allows me to sleep, is that I’ve been trained to think about how to make things work— when you’re broke and when you have a little bit of cash. When I was broke, I need hope as a currency. I needed to know that even though I didn’t have very much, this work that I was doing was very important. I needed that, right?

It gave you motivation.

When I didn’t have a job, I started working as a mason’s tender, almost breaking my back. I needed to think, “I love working with my hands, I love clay, I love building stuff, and this guy is doing good work in the ‘hood, and it’s hard work, but I’m going to do it even though he’s not paying me a lot of money. I won’t be a mason’s tender all my life; this is just a tough moment.” Then, the other side was when I had extra money, and I could pay for all my friends to go drinking. I remember this night at Skylark in Chicago—I could buy everybody four rounds. There were ten of us. It was like, “Damn!” When you have extra, you want to disperse it. I’ve been thinking about that. What do you do when you have extra? Well if you still maintain that earlier ethic, it just means that you can get more done faster. I’m just doing the same stuff, but maybe I don’t have to ask as many people, or I can hire more people to help me.

You’re spreading it out.

But even if we’re talking about the philanthropic community, I could say, “I’m not coming to you as a grassroots person in need. We’re both interested in solving this problem. Would you like to partner with me in order to think about this project?”

You’re in a very interesting position because the scale of the project to rethink urbanization in the US is enormous. We need models, and part of your work is reimagining how to address this complexity in new ways. This also affects the art world and the global debate.

Because of my training, the city is my medium. If the city is ill, then I have a subject, I have a patient. And that’s exciting. I started to think, how does my love of cities and my care for the built environment live alongside a rigorous life practice? What are the different stations of the practice? Those stations might include learning a lot about art and a little bit about real-estate law, governance of a city, developers and where the money come from, which means knowing a little bit about federal policy.

So you’re bringing all your training and background to each situation.

That’s one set of tools. Then there’s clay. I love clay. I have the craftsman’s belief that you should be excellent at something and that there’s a history and a pedagogical approach to a thing. I want to be a good craftsman as much as I want to be a good leader, and I don’t think I have to choose between leadership and craftsmanship.

In each situation, you’re building, you’re constructing.

I’m constantly making decisions that consider the symbolic effect that I want to ring in the city. If it’s a reflection on a 1960s moment of struggle, and a fire house helps me to articulate that, it’s like, “Let me just stay here for a minute until I find a way to bring us back to materiality in relationship to that political moment. Let me reflect on my history, where I experienced a certain kind of poverty, and the fact that my dad was a roofer. Let me get some shine to my dad at seventy-nine or eighty, give him some flowers while he’s living.” It’s completely sentimental. What first drew me to creating a roofing painting was the fact that he was retiring. Could a certain amount of sentimentality in relationship to this bigger conversation about black labor and the urban condition lead to a body of work that I felt really good about, with my dad as my collaborator? Sometimes I want to make paintings with tar; sometimes I work on the roof with my dad because I’m after a set of relationships. The objects are just the things that allow me to continue the relationship with my dad. It’s not to say that I don’t care about the tar painting, but the tar painting gave us a reason to relate.

Theaster Gates creating one of his tar paintings, Chicago, 2012.

Theaster Gates creating one of his tar paintings, Chicago, 2012.

It was a vehicle, not an end in itself.

I invent a lot of time in these paintings. I love constructing them. They represent a set of relationships that are important to me, and they’re symbolic of a moment when black men were extremely capable builders and built this country. And we’re not that anymore. And so the works are a relational practice with my dad, a collaborative effort between him and me. They’re a set of objects that are made. Now I’m looking at roofs and the sublime. I’m looking at Shinto structures and how these old Japanese Buddhist temples were made so that the roof actually help up the walls. I’m learning all this stuff about fourteenth-century cathedrals. I’m just kind of interested in roofing.

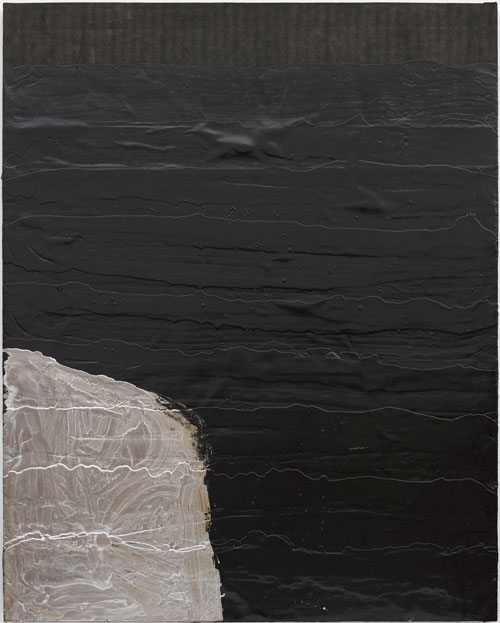

Theaster Gates,

Mountain Monument

, 2014

Theaster Gates,

Mountain Monument

, 2014

[….]

There’s a whole discourse that you use in your practice that revolves around place-making and meaning-making. But you don’t use the words others attach to your work, such as “moral,” “ethical,” “political,” or “transformative.”

You know, having a history so rooted in organized religion and organized morality, and in a slightly militarized culture where the law didn’t seem to be working for me—even though it was supposed to have been written for me—I have a lot of resistance when people say the work is a kind of activist practice. When Thomas Hirschorn did his Gramsci project in the Bronx, it still felt like high art. But when black artists do things in the ’hood, it becomes “community art,” rather than place-based work. I’m reminded of the Situationalists’s notions of radical urbanism and how they were influenced by the call-to-arms of the Watts riots in 1968. The term “community,” while it encompasses a part of the work’s aspiration, doesn’t quite match the larger investment that I’m engaged in. I’m engaged in an open dialogue concerning the challenges of people’s right to the city—our total right to live fully, govern thoughtfully and have our desires fulfilled as much as our needs met.

But your work moves in all of these worlds simultaneously. How do you do that?

By understanding the value of polyvalence—that one act can have multiple effects, and several acts together create permanent imprints on the imagination of the city.

[…]

The art world is fundamentally symbolic. Artists can’t get over the notion that their gallery has to be in Chelsea or that they need to be in a particular collection. It’s an old patronage system, and it keeps artists dependent.

Sad, isn’t it?

Yes, because it gives away power. Artists have yet to internalize their importance to US society.

I listen to folks talk to theatre kids, for example, saying, “You’re going to have to get a waitressing job because if you want to do this thing that you’re passionate about, you’re going to have to wait tables.” And I think, “Man isn’t there something else we could say to a creative person with a set of skills?” I want artists to understand that in the absence of a gallery or a museum, they have the capacity to invent the platform by which they can express their beliefs.

And you know how they learn that? By looking at people like you. The whole art-school world is too often still based on the nineteenth-century atelier—the Romantic artist destined to starve (or to be a waitress). Young artists need to learn to channel their uniqueness. They need to see people who are fearless in starting and trying new forms of practice.

[…]

Artists are afraid to fight the real-estate battle or the tax battle. They’re afraid they’ll get ostracized. As your role and interests in society expand, do you ever think you might take these issues even further into the political arena?

No. Can I tell you why not? In some weird way the political and the moral conflate, and I think my practice is political enough. While I don’t identify as an activist, I do recognize the value of an ethical life and the importance of fighting for the things you believe in.

One of the things that draws people towards you is a joyfulness in your person and in your work, a state that surely would be impossible to sustain in politics. You talk about race, but you’re not clobbering people with it. You address social issues, but you give people room. You’re very invested in the African-American community, but you don’t exclude white people and others. Where does that openness and playfulness come from?

I really think that joy is a gift of black folk. There’s a way in which one learns to be one’s own super-self, having experienced trauma and having to figure out how to survive in spite of that. And the more that I come into contact with certain kind of generational wealth (just speaking in generalities here), I see that melancholy seems to follow comfort. The thing I worry about for myself, now that my problem isn’t fiscal, is where will the tension come from? When do hip-hop artists become bad hip-hop artists? It’s at that moment when the record goes platinum. They make some cash, and then everything that was sexy about what they were writing about becomes, “Oh you don’t live in Compton anymore?” Then you’ve got to find new things to rap about. I feel like maybe that’s why I haven’t left Dorchester; maybe I just need to continue to feel alive and continue to be around normal black folk. Maybe I’m just a ‘hood rat. I never thought of myself as a joy-production machine, but it seems to be so.

It’s part of why people want to be around the projects. And I’ve been thinking, too, that you started with a great love of craft, the making of things with ceramics and clay that continues to inspire you.

And it was communal—not like the lone potter, but like the workshop, Japanese style.

And you’re still creating vessels.

I feel I’ve never really left clay. If I think about clay more abstractly, the vessel makes space. It defines space, and then once that space is made, things can happen. Space is the material for the city, and I have the capacity to create a cultural district that has really clear parameters. As a result, an interesting tax sensitivity could happen—a special zoning for a “Black Cinema House” dedicated to screening films about (and made by) the diasporic image makers of the world that would allow for the creation of a brick-manufacturing company that can then build other buildings.

Interior view of Black Cinema House in Chicago.

Interior view of Black Cinema House in Chicago.

Maybe the way to avoid becoming the boring platinum rapper is just to follow these instincts.

Right now, the best thing I can do is just keep working. But there is this way in which additional opportunity creates new responsibility; figuring out how to balance it can be a little bit challenging.

[related-works-module]