Tracey Emin

's sculpture

My Bed

(1998) is exactly what it sounds like: the work consists of the artist's freshly slept-in bed, with crumpled pillows, disheveled sheets, and dirty tissues and other junk (including sanitary items, prophylactics, and liquor bottles) strewn around the footboard. When it debuted at 1999 at London's

Tate

, it created an instant commotion in the media—according to the

Sunday Mirror

, the piece prompted thousands of grumbling letters from readers about the "so-called art work." Meanwhile, a "furious housewife" was apprehended by museum staff when she attacked the piece with cleaning products.

All of which is to say that

My Bed

is the kind of artwork that prompts the timeless response: But is it art? To which we reply: Of course it is—because Emin said so. But there's more to the story. The key to fully understanding the complex operations of contemporary art that may, to the untrained eye, seem lawless and unskilled, is to understand the concept of "the readymade" in the history of 20th-century art.

SEE ALSO: Available Found Object Artworks on Artspace

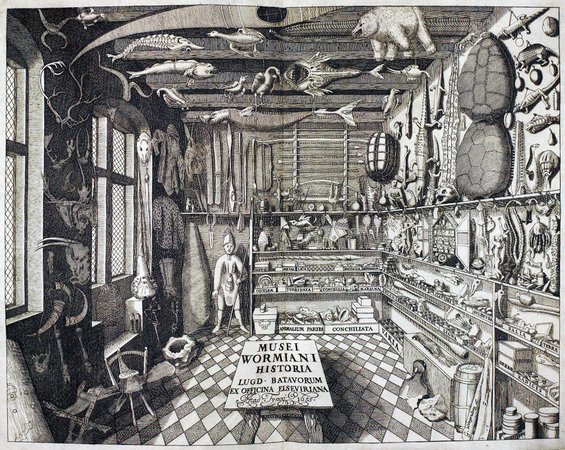

A 16th-century

Wunderkammer

A 16th-century

Wunderkammer

The amassment and display of found objects for their aesthetic qualities dates back to at least the 16th century, when the collections of individual enthusiasts were displayed in private "cabinets of curiosities," or what the Germans called "

Wunderkammer

." But it wasn't until the 1900s that artists began to incorporate found objects into sculptural works as an artistic gesture. The term "found object" is a literal translation from the French

objet trouvé

, meaning objects or products with non-art functions that are placed into an art context and made part of an artwork; what we now call "the readymade" is an updated version of that idea.

Marcel Duchamp

is usually credited as inventing the readymade, but the essential idea of taking something preexisting and elevating it into art did exist before he created his first one (a bicycle wheel atop a kitchen stool) in 1913: in

Pablo Picasso

's

Still Life With Chair Caning

from 1912, for example, the artist collaged a piece of woven chair backing onto a two-dimensional canvas, and before that

Degas

clothed his

Little Dancer of Fourteen Years

(1881) in a real tutu. Much of early modern art was concerned with representation and how to reconcile art's illusionism with its real object status (think of

René

Magritte

's

Ceci n'est pas une pipe

from 1929). As part of that greater conversation, the

objet trouvé

was understood to be a raw material used in an assemblage in a way that called attention to its real material qualities and inherent aesthetic. Taking this idea one step further, Duchamp's readymades invented a new category of artworks composed entirely out of manufactured, pre-made objects that stood on their own as autonomous works of art.

[magritte-related]

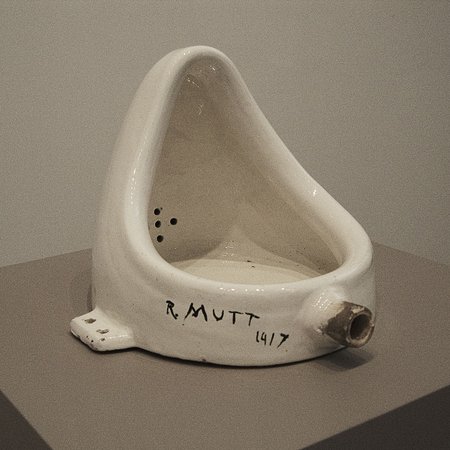

Marcel Duchamp's

Fountain

, 1917

Marcel Duchamp's

Fountain

, 1917

Duchamp's

Fountain

of 1917

is the artist's—and perhaps the world's—most famous readymade sculpture. Duchamp submitted the work, simply consisting of a porcelain urinal that's been placed on its back on a pedestal and signed "R. Mutt" by the artist, for an show at the

Society of Independent Artists

in 1917. It was rejected by the exhibition committee, but is now considered a foundational work for much of the artistic experimentation over the past century. Other items that the artist transformed into "pure ready-mades," as he called them, included a bottle rack (

Bottle Rack,

1914) and a snow shovel (

In Advance of the Broken Arm,

1915).

RELATED ARTICLE: Duchamp Probably Didn't Make the "Fountain" Urinal—A Look at the Dada Woman Who Likely Authored the First Readymade

Duchamp's appropriations of everyday objects had far-reaching implications, and continue to shape the conversation around art today as a primarily intellectual, rather than strictly material, pursuit, a product of the artist's mind rather than one of manual skill honed to technical perfection. (“I was interested in ideas—not merely in visual products,” said Duchamp.) Almost immediately, artists associated with European Dada took up the torch from 1916 through the 1920s, resulting in works like

Man Ray's

The Gift

(1921), a flatiron with brass tacks attached to its underside, rendering it bizarrely useless. Later, in the '50s,

the artist

Arman

embedded money, garbage, and entire cars

inside his sculptural works.

RELATED ARTICLE: A 1959 Interview with Marcel Duchamp: The Fallacy of Art History and the Death of Art

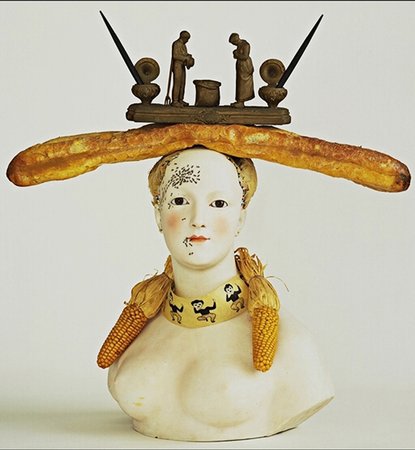

Salvador Dalí's

Retrospective Bust of a Woman

, 1933

Salvador Dalí's

Retrospective Bust of a Woman

, 1933

Later in the century, the artists associated with

Surrealism

, including

André Breton

, emphasized the act of the artist's choosing of an object as the definitive moment in an artwork's conception. The Surrealists, informed by the psychoanalytical work of

Sigmund Freud

, also believed in the efficacy of powerful subconscious associations with objects, which gave their assemblages an added level of theoretical obfuscation that often translates into wry humor.

From the '40s on, American

Abstract Expressionism

dominated the Western art landscape and returned many artists' attention to the evocative formal qualities of paint on canvas and traditional sculptural materials—although the biggest figure associated with "Action Painting",

Jackson Pollock

, also stuck detritus including cigarette butts, coins, buttons, and keys onto the surfaces of his paintings. Meanwhile, sculptor like

John Chamberlain

made large-scale, formally impressive sculptures out of crushed wrecked cars. In other words, despite the nearly militant formalism propounded by artists at the time, Duchamp's radical idea had penetrated to the deepest core of the collective artistic consciousness.

Piero Manzoni's

Merda d'Artista (Artist's Shit)

, 1961

Piero Manzoni's

Merda d'Artista (Artist's Shit)

, 1961

The '60s saw the Duchampian readymade extended into the world of commercial goods with the age of Pop . Andy Warhol is the best-known practitioner of appropriating images from popular culture, but his work focused mainly on reproducing images; whereas artists like Marisol Escobar , at the same time, incorporated objects bottles of Coke and other consumer items directly into their works. Italian prankster conceptual artist Piero Manzoni famously challenged the idea of the readymade in 1961 when he made Artist's Shit ( Merda d'Artista ). Manzoni's specious claim was that he had actually canned and labeled his own excrement, poking fun at the idea that any item touched by an artist could be transformed into a great work of art—while also, ironically, taking the same notion to its logical extreme. His joke continues to be played out in the market: a can sold for $ 166,618 at Sotheby's in 2008.

RELATED ARTICLE:

Eww! 7 of the Grossest Contemporary Artworks

In many ways, the readymade is the direct ancestor of all conceptual art that followed, in that it allowed artists to consider and refine the crafting and presentation of an idea rather than focusing on material means.

Conceptual art

in the '60s and '70s focused on "the dematerialization of the art object"—in the phrase of critic

Lucy Lippard

—in favor of documentation of ideas, actions, and

processes

as artworks. However, the material-centric history of the readymade actually played a major part in this shift, as illustrated by works like

Michael Craig-Martin

's

An Oak Tree

(1973). In that work, Martin displayed a glass of water alongside a text proclaiming that he had "changed" the glass of water into an oak tree, setting the mundane material reality of his work in stark contrast with its conceptual presentation.

Haim Steinbach's

Untitled (cabbage, pumpkin, pitchers)

, 1987

Haim Steinbach's

Untitled (cabbage, pumpkin, pitchers)

, 1987

In recent decades, artists have continued to explore ways of incorporating readymade objects into their work, including through a strain of the approach that takes off directly from the fetishization of consumer goods. German artist

Isa Genzken

, who recently had a major retrospective at

MoMA

, is well known for her sculptural work since the early 2000s, which is made up of both items that the artist finds on the city street and high-end pieces of designer furniture purchased from stores. Other artists, like

Haim Steinbach

,

have crafted visual languages that place everyday goods in arrangements that use repetition and formal contrast to push even further the idea that artist's role is to select items and serve them up in unexpected or meaningful juxtapositions.

While the Duchampian lineage of the so-called readymade distinctly belongs to Western art history, some variations on the same idea do exist outside of the European canon. For example, Senegalese sculptor

Moustaphe Dimé

, for whom the French term

recuperátion

would be a more familiar word for describing what he does, has made sculptures out of pieces of driftwood and other cast-off or discarded materials; the Republic of Benin's

Romuald Hazoumè

creates portrait busts from jerry cans

. The non-Western history of such appropriative practices, however, is largely yet to be explored.

[found-object]

RELATED ARTICLES:

A 1959 Interview with Marcel Duchamp: The Fallacy of Art History and the Death of Art

Think About It: 9 Masterpieces of Conceptual Art You Need to Know