Art styles and movements are created or identified many different ways. Some are fashioned by artists themselves, groups of like-minded people who share a similar way of thinking or looking. Others are created in retrospect, by historians who seek to understand art based on shared techniques or themes. Yet others are born of political causes or in reaction to social or cultural circumstances—an attempt to alter history, or reinforce the status quo, or reject both history and status quo altogether in a determination to start again.

Phaidon's Art in Time (from which this article is excerpted from) introduces some 150 of the most important and influential styles, schools, and movements, spanning not just the Western tradition but also styles from India, China, Japan, Latin America and Africa. Beginning with the present day and moving back in time, the reader is encouraged to discover the ways art plays with, and builds on, earlier ideas, beliefs and traditions. And that's just what we're doing here. We've excerpted the movements and styles that took place in China, to see how these movements may have influenced one another, and culture at large. Below you'll find four, from XinJiang province to the East China Sea.

NEW CULTURE MOVEMET

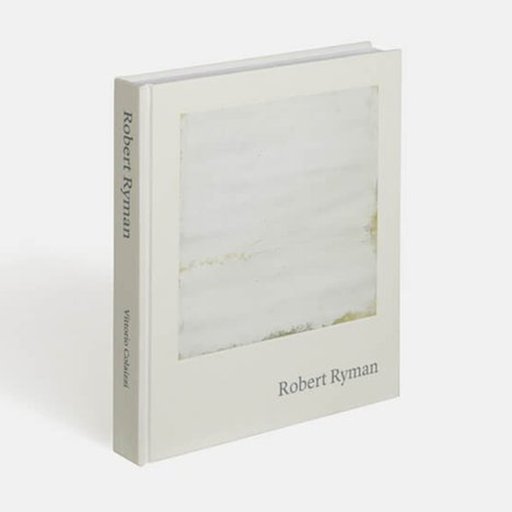

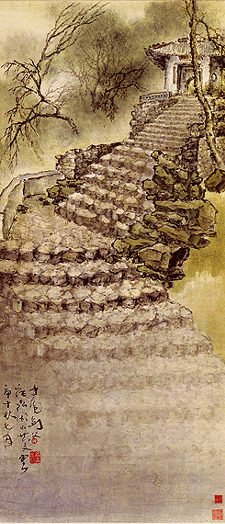

Gao Jianfu, Temple at Dusk, 1930. Image via www.cuhk.edu.hk

Gao Jianfu, Temple at Dusk, 1930. Image via www.cuhk.edu.hk

The New Culture movement refers to a burgeoning of creative and intellectual output in the 1920s that brought about the modernizing of Chinese culture. It stemmed from the may Fourth Movement of 1919, a student protest against the undermining of China’s power at the hands of foreign imperialists and its perceived weakness against Japan’s military expansion. The movement was borne out of a strong sense of discontent with Confucianist culture among urban intellectuals, and it affected developments in art and literature throughout the whole of the twentieth century.

In art, the key debates stemming from the May Fourth Movement revolved around issues of Westernization and the modernization of Chinese culture. Key themes within the New Culture movement were ideas of scientific advancement and democracy, Chinese nationalism and cosmopolitanism, modernization and Westernization, and anti-Confucianism. A number of artists had the opportunity in the early twentieth century to study in Paris, which significantly influenced their work and combined with these themes to allow for experimentation within a wide range of styles. Some artists were heavily influenced by European modernism, while others, such as Gao Jianfu (1878-1951), attempted to modernize Chinese ink painting with elements of Western Realism. Gao used traditional Chinese ink in his Temple at Dusk , but the painting exhibits clear influence from both the West and Japan in its atmospheric use of perspective and shading.

The New Culture movement was disrupted and displaced when the Communist Party began to triumph in the 1940s. The more progressive cultural atmosphere gave way to a strongly ideological one that proposed an artistic system “for the masses” within the Maoist conception of the communist superstructure. From the late 1930s, many artists who had developed new forms of Chinese modernism were unable to continue their art until the thread of modernism was picked up again in the late 1970s. Nevertheless, the movement had a profound effect throughout the twentieth century and continues to be influential as a platform for the diversification and expansion of art practice in China in the twenty-first.

CHINESE WOODBLOCK MOVEMENT

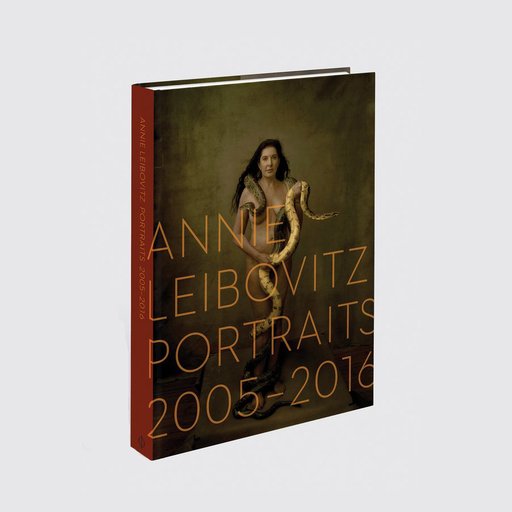

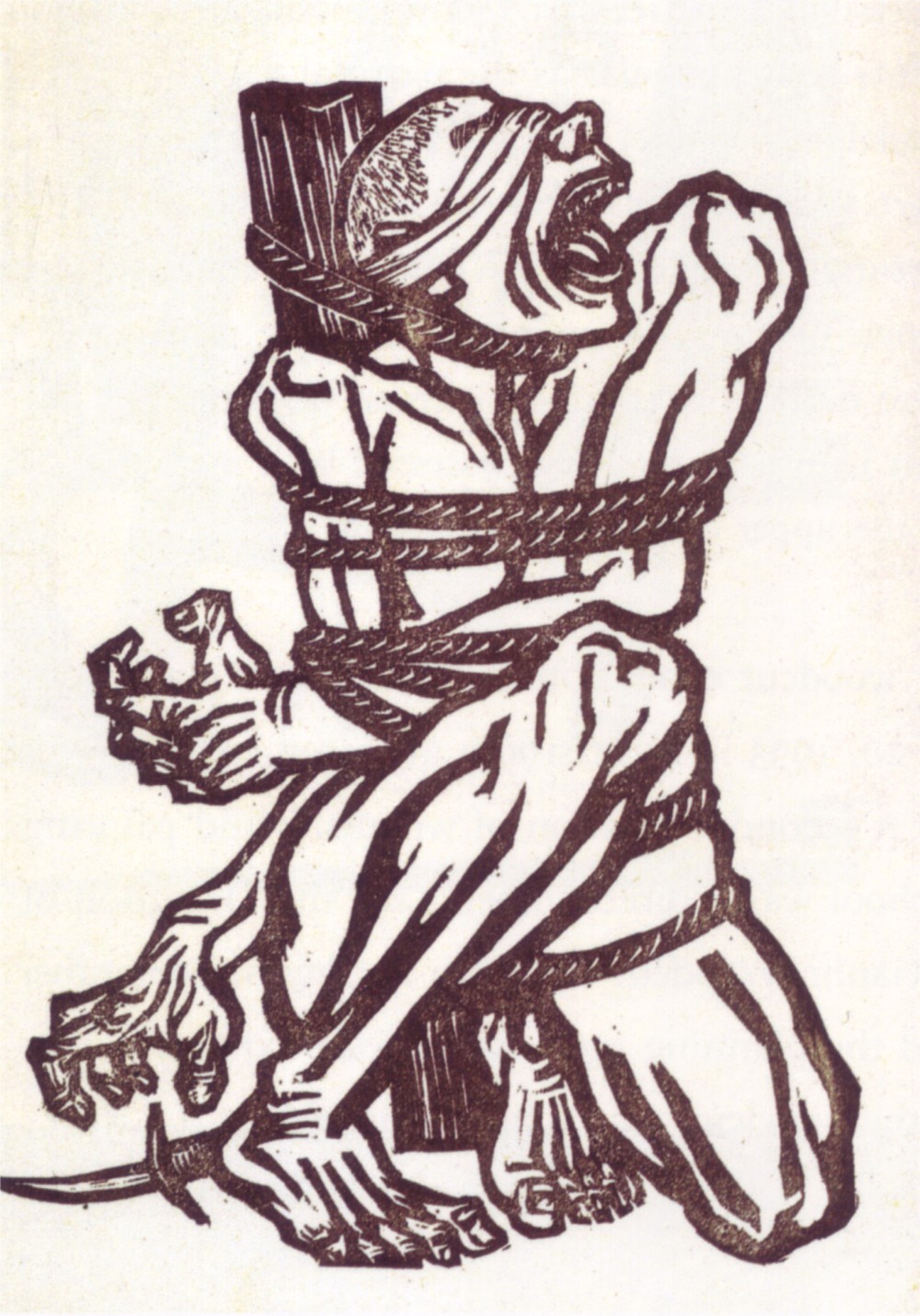

Li Hua,

Roar, China!

1935. Photo via aphelis.net

Li Hua,

Roar, China!

1935. Photo via aphelis.net

The Chinese modern woodblock print movement flourished in the 1930s in a cultural climate in which intellectuals and artists were attempting to communicate social and political critique in China through visual means. Led by the left-wing writer and critical essayist Lu Xun (1881-1936), who had studied in Japan, the movement took off after Lu invited a number of art students to apprentice under Japanese printmaker Uchiyama Kakechi in 1931, following an initial exhibition of woodblock prints in Hangzhou in 1929. It gained momentum as a result of artists’ concerns with pressing social issues that were facing China as it struggled to modernize, along with the military threats from Japan that threw the country into full-scale war by 1937.

The visual impact of translated and illustrated publications from Russia and Germany fed into the Chinese Woodblock Movement, which shows clear links to German Expressionism and European engravings. Artists such as Kathe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Clement Moreau (1903-88) and Frans Masereel (1889-1972) were highly influential on the movement for their succinct visual language in the woodcut form and their ability to portray clear messages about social injustice, abuse by exploitative landlords, conditions of severe poverty and political unrest. The development of an urban cosmopolitan culture of literary and cultural journals was also a key factor in the Woodblock Movement due to the kinds of designs and illustrations published that exposed a range of foreign styles to China.

Roar, China!, by Li Hua (1907-94), is the most iconic of the Chinese woodcut images of the 1930s. As a powerfully intense visual personification of China’s sense of enslavement as an emergent nation, it shows the clear influence of German Expressionism in the extenuated lines of the feet and hands and the emotionality of the image. Later woodblock prints of the 1940s adapted earlier works to merge with aspects of the New Year printmaking (nianhua) tradition. Already a long-standing practice in China with its roots in rural artistic traditions, celebrating the New Year involved the temporary pasting up on doors and windows of prints with traditional motifs, such as door gods and plump babies, symbolizing fortune, fertility and prosperity. Once the Communists founded their base in Yan’an in the northwest of China, artists who had previously been based in urban centers adapted their style for an illiterate peasantry in answer to Mao Zedong’s call for artists to use traditional styles already familiar to the Chinese people.

The Woodblock print movement strongly influenced the style of propaganda posters made in the first two years of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), a period of fundamentalist Maoism when some of China’s most distinct revolutionary imagery was produced.

GUOHUA

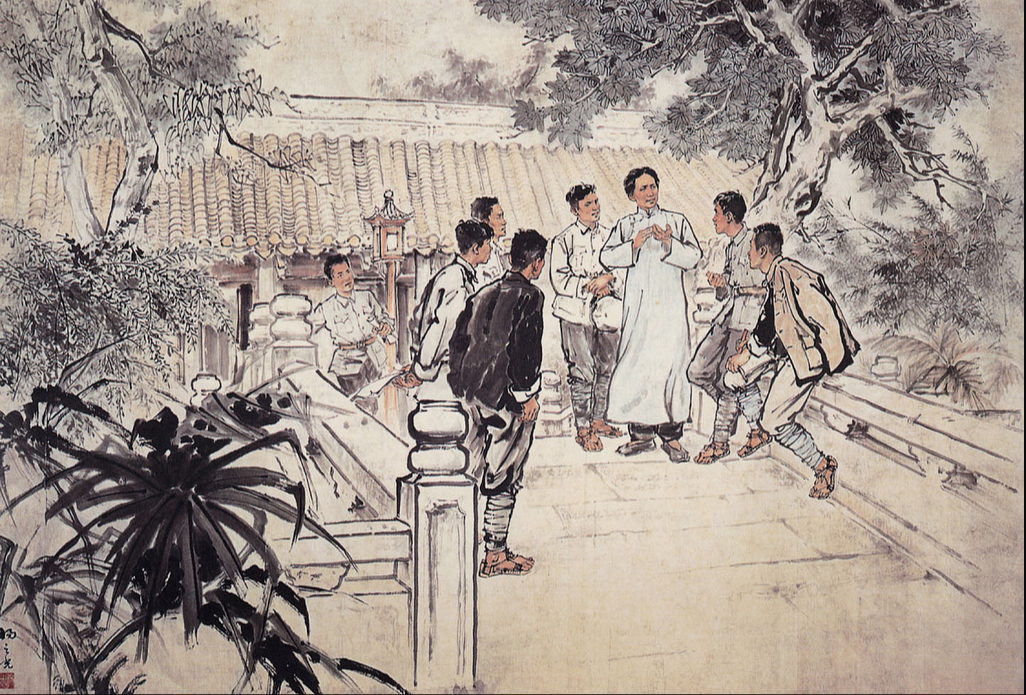

Yang Zhiguang,

Mao Zedong at the Peasants Training School

, 1959. Image via Flickr

Yang Zhiguang,

Mao Zedong at the Peasants Training School

, 1959. Image via Flickr

The term guohua (national, or Chinese painting) emerged under the late Qing dynasty (1644-1911) and relates to the transformation of Chinese ink painting within the context of the modernization of Chinese art in the twentieth century. Broadly speaking, it refers to a new genre of ink painting involving a reinterpretation of traditional literati painting. Literati painting was a sophisticated tradition of ink painting that had developed over centuries as an amatuer scholarly practice associated with a highly cultured elite who pursued poetic refinement and philosophical depth in their works. These attributes became problematic in a rapidly changing society, as literati painting was deemed insufficiently allied with the aspirations of a modern nation asserting itself in the world order.

Reform of art and culture was active during the Republican era (1911-37) as part of the New Culture movement, but once the Communist party came to power in 1949, there was a complete restructuring of the art system within the new regime. This system categorized acceptable forms of art, including guohua, oil painting, New Year pictures (nianhua) and picture stories (lianhuanhua) in order to ensure that art played an effective role in promoting socialism for the new society. Guohua was considered conservative and allied to old values because of its adherence to traditional materials, particularly when compared to Soviet-influenced oil painting in the Socialist Realist genre, which was encouraged in the early to mid-1950s. By modernizing literati painting, some of the essential aspects of that tradition were necessarily excluded, so that its quintessential features of cosmology, poetics, the trace of the individual artist’s brush strokes within the landscape’s journey and so on were replaced with a very different set of cultural and political values.

Guohua was constructed as a modern form of Chinese ink painting, promoting new, twentieth century themes and often focused on celebrating the achievement of the revolution. Fighting in Northern Shaanxi by Shi Lu (1919-82), merges aspects of Chinese ink traditional art such as the strong “axe” brushstrokes in the foreground with a square format and large scale, emphasizing a sense of grandeur with an overtly political theme. Another good example of guohua is Mao Zedong at the Peasants’ Movement Training School, set in the 1920s, which depicts Mao as a young instructor teaching a class to peasant soldiers who will contribute to the revolutionary cause. A figurative work in ink, it can be seen as both representational and poetic, executed in sweeping brush strokes, depicting a historical scene of early revolutionary activity with Mao as the central figure. Ultimately, the ideological construction of guohua as a category in the twentieth century forced many ink painters into a position of subservience to the political demands of the day.

‘85 NEW WAVE

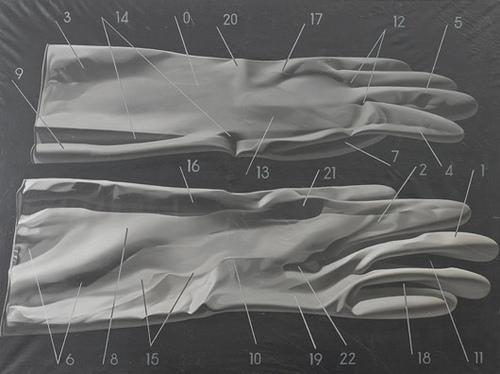

Zhang Peili,

X?

, 1986. Image via Flickr

Zhang Peili,

X?

, 1986. Image via Flickr

The ‘85 New Wave, also known as the ‘85 Movement, refers to the proliferation of artistic activity by artists working within groups in cities all over China during the mid-1980s. The momentum of this collective movement underpinned the Chinese avant garde that emerged internationally in the early 1990s and would later have a significant impact on an increasingly globalized art world.

The regional aspect of the ‘85 New Wave is crucial to understanding its diversity and variety. Many of the groups reflect this in their names: The Southwest Group in Sichuan (Including Mao Xuhui, Zhang Xiaogang, and Ye Yongqing), the Northern Art Group in the city of Harbin (Wang Guangyi and others), the Red Brigade Group in Nanjing, and the Pond Society in Hangzhou (Zhang Peili and Geng Jianyi). Many of the artists involved in these groups were recent graduates from art schools that had reopened after the Cultural Revolution at the end of the 1970s. They were exploring new styles, themes, and subject matter in painting as well as using new types of media—assemblage, early forms of installation art, and object-based works—to move beyond conventional forms.

The themes that preoccupied this movement stemmed largely from questions of humanism, rationalism, idealism, and subjectivity, which were used to critique the dominant canons of Western and Chinese art history. In The Second State, by Geng Jianyi, the huge, Photorealistic painted portrait faces are ambiguous: on the one hand they seem overcome with irrepressible laughter, but their expressions can also be read as cynical sneers or terrified screams. The theme of control and dehumanized hyper-rationality is rigorously explored in the “X” series by Zhang Peili (b. 1957), with its sharply drawn clinical rubber gloves and their associations of surgical hygiene and institutional control. Other ‘85 New Wave artists drew on native references through lyrical depiction of the countryside, following the new genre of Rustic Realism prominent in the Western region of Sichuan.

The public culmination of the ‘85 New Wave was the large-scale exhibition “Modern Chinese Art,” held in the National Gallery of Art, Beijing, in February 1989, after which the “China Avant-Garde” exhibition circulated in the West in the early 1990s. Its key players became artists of considerable success. Themes that emerged during this period arose out of opposition to the predominant politicization of art during the previous two decades and as a reaction to the rigid academic training of the academies. The European repertoire of Surrealism, Cubism, Dada, and Expressionism inspired artists to break away from decades of Socialist Realism. She X He by Gu Wenda (born 1955) is a classic example of the deconstruction of language and its relationship to assumed notions of identity.

An important aspect of the ‘85 New Wave was its appropriation and assimilation of philosophical texts read widely by many Chinese artists eager to catch up on ideas after years of narrow political dogma. Chinese conceptual art emerged out of such cross-cultural collisions of historical moments and philosophical positions, and established European avant-garde influences were immediately translated into contemporary Chinese art.

RELATED ARTICLE:

China's New Guard: Three Painters Upending the Past, Present, and Future of the People's Republic