The value of an artwork can often seem more capricious and abstract even than the work itself. Just look at the 2017 sale of an alleged Leonardo Da Vinci painting, Salvatore Mundi for $450 million at Christie’s; or Kenny Scharf’s ceramic bong sculptures on sale at the Whitney Museum gift shop for the punny price of $420. As perplexing as the price tag of an artwork can be, what is perhaps even more confounding is what happens to an artwork’s value once it's destroyed—especially when "destroyed" might simply mean "dented," "stained," or "torn."

Gallerists and art handlers alike have recurring nightmares about all of the ways that an art install can go awry; and if you're clumsy like me, you lay awake at night with the irrational fear of accidentally tripping over your shoelace and diving headfirst through a Hockney painting. A parody of this sort of disaster is the 1997 film Bean, in which "Dr." Bean (Rowan Atkinson) sneezes on a $50,000,000 painting, Whistler's Mother (1871), just before it is to be unveiled at an L.A. gallery. In a series of deliciously entertaining mishaps, the character destroys the painting beyond repair, and resorts to drawing a phallic-nosed smiley face in blue pen ink over the smudged disaster. (Personally, I think he fixed the work, but that's just me). Obviously this restoration doesn't quite fly with the gallery’s curator, so Mr. Bean concocts a scheme to replacing the work with a poster from the gift shop, attached with chewing gum and glossed with a combination of eggs and clear nail polish. No one notices the difference (which doesn't come as too much of a surprise, as the man who bought the work admits that he doesn't "know the difference between a Picasso and a car crash") so Bean keeps the destroyed original, and tacks it up in his bedroom.

Whistler's Mother, Bean (1997), Image courtesy of iMDb

Whistler's Mother, Bean (1997), Image courtesy of iMDb

While this is a hysterical commentary on the art market, this scheme probably wouldn't work outside of the context of a cheesy '90s comedy film. However, valuable artworks do get damaged quite often. There have been a number of catastrophic botch jobs over the years, from the man who famously tripped at Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum in 2006 and shattered not one, but three priceless Qing Dynasty vases; to the handlers who accidentally sent a 1960s Lucien Freud painting packed for an auction at Sotheby's to a crusher, followed by an incinerator in 2010; to the 12-year-old boy who tripped and punched a hole in a 350-year-old, $1.5 million Italian Baroque painting by Paolo Porpora at an exhibition in Taiwan; to the woman who famously knocked over a series of pedestals domino-style at L.A. gallery The 14th Factory, while trying to take a selfie with the work of British multimedia artist Simon Birch, causing nearly $200,000 in damages.

Luckily, because human error is a universal truth, there is insurance for these sorts of accidents. Once an artwork is destroyed—like, say, Jeff Koons's Red Balloon Dog, which was dropped and shattered beyond repair in 2008—it is legally deemed worthless. Essentially, when the cost to repair an artwork is more than the work is worth, insurance agencies declare the work "salvage art," or "no longer art."

But herein lies a moral conundrum: because insurance companies must recieve proof that an artwork is damaged beyond repair before doling out insurance payments, destroying an artwork for the sake of an insurance claim is not entirely unheard of. Consider this scenario: The corner of a $5,000 limited edition print is bent during transit. Although the small dog ear on the corner of the paper doesn't affect the image in the slightest (no reasonable person would consider the work "destroyed"), the damage could prevent the dealer from selling it. Why would a collector pay $5,000 for a slightly damaged print when they could pay $5,000 for a different print in the same edition that's in perfect condition? So, the dealer is left with a difficult decision: hold onto inventory that is technically valuable, but practically value-less on the free market, or, destroy the inventory beyond repair, making it technically valueless and thus redeemable for an insurance payout. Yikes.

So, what actually happens to these artworks that become destroyed, whether by clumsy mishap or for insurance purposes? Do the remains just go to the trash? Well, sometimes, yes, that is exactly what happens to them (that would be one hell of a dumpster dive find). Most often, however, the destroyed works are kept in a warehouse: a mausoleum of sorts for forgotten art (sort of like the Island of Misfit Toys). If that makes you cringe, you can rest easy knowing that one artist, Elka Krajewska, does find value in these works deemed valueless. In 2009, the Polish-born artist founded the Salvage Art Institute in New York City, after she was startled to learn that a number of damaged artworks declared legally worthless but not completely destroyed were housed in warehouses owned by insurance companies. She reached out to AXA Art, one of the most prominent contemporary art insurance agencies, to inquire whether she might obtain some of these works. AXA donated about 50 works to the Institute, which put together an exhibition titled "No Longer Art" at Columbia University (where viewers were actually allowed to touch the works and put their arms through holes in the paintings; what a treat!). The works were displayed alongside the legal documents which stated their respective damages.

Destroyed Jeff Koons sculpture, on display at SAI, Image courtesy of Chicago Magazine

Destroyed Jeff Koons sculpture, on display at SAI, Image courtesy of Chicago Magazine

Krajewska is most interested in the radical transformation of a work's value by such a simple task as legal reassignment. It is especially hard-hitting when the work is by Jeff Koons , whose practice is intrinsically linked with the monetary value of the works. (Koons reportedly didn't understand SAI's goal to create a democratic exhibition space in which the works were liberated from their market value). Krajewska seeks not only to give the works a second life, but to incite a conversation about the true value of art. The project turns the traditional tropes of conceptual art, specifically the notion that any object can be art, on its head, "confront(ing) and articulat(ing) the condition of no-longer-art-material claimed as 'total loss,' resulting from art damaged beyond repair, removed from art market circulation due to its total loss of value in the marketplace." The art in Krajewska's exhibitions is a haven for art which fits a specific set of conceptual guidelines that comically mimic legal speak: the art must "be liberated from the obligation of perpetual valuation and exchangeability," and "maintain the zero-value of 'No Longer Art'... divorced from the demands of future marketability." The collection is non-hierarchical, as each legal declaration of 'total loss' cancels out the artist's signature. ("No Longer Art" has been exhibited internationally, and is currently on view at BNKR in Munich, Germany through February 25, 2018.)

...

In some cases, the destruction of an artwork can actually cause the work to accrue in value, as in the case of the laughably dreadful attempted restoration of a 1930 Elias Garcia Martinez fresco painting of Jesus Christ by Cecilia Gimenez in 2012. The result was so bad that it lit up the internet like wildfire, making the local church in Borja, Spain a widely-sought destination for over 130,000 tourists. The work, which would ordinarily have been seen by very few people, became a worldwide phenomenon, and served to stimulate the local economy of the struggling town. Without knowing it, Gimenez was painting one of the most conceptually interesting pieces of the 21st century. The power of the meme came to the fore of the art world, articulating a shift in the general sentiments and values of the modern public and proving that a new lexicon was at play; one in which humor played a major role.

"Botched Jesus," Image courtesy of NYPost

"Botched Jesus," Image courtesy of NYPost

In a field that is so reliant on concept and theory, contemporary art blurs the line between mistake and intention in a unique way. Some actually speculated that the incident at Simon Birch’s exhibition at The 14th Factory may have been staged, and even Birch himself wrote that “perhaps it (was) ironic and meaningful that (the crown sculptures) fell." Whether staged or not, the event definitely got the exhibition more press, and could very well be interpreted as a conceptual component of the work. This blur between what's real and what isn't is also why we consistently hear gallery instances so absurd, you couldn't make them up: such as viewers believing that a pair of eyeglasses left on the floor by teen pranksters at SFMoMA was a sculpture in 2016; or a brutal X-Acto knife stabbing at Miami Art Basel was misinterpreted by visitors as a performance art piece in 2015.

The paradox of modern and contemporary art is that while accidentally knocking over a display at a museum or gallery is a concept so cringe-worthy it verges on taboo (or prime material for comedy skits, as in Eric Andre's cathartic gallery destroying stunt), the destruction of art is a fundamental aspect of its historic context. Artists have been deliberately making a mess of things to further the conceptual dialogue of art for decades. In a piece titled “Damage Control: The Modern Art World’s Tyranny of Price,” published in Harper’s Magazine , critic Ben Lerner writes that “much of the story of twentieth-century art can be told as a series of acts of vandalism.” He quotes Picasso, who famously referred to his work a “sum of destructions.” Modern and contemporary art history is essentially a series of artists usurping the expectations of the movements and "isms" which came before them. Says Lerner, "what’s clear is that modern art is inseparable from the destruction of modern art... Demolition, defacement, and debasement are not just fates artworks suffer at the hands of vandals; they’re often what those works are."

Once the practice of making art became led primarily by concept , some artists took to usurping what came before them in the most literal way possible. In 1993, a man named Pierre Pinoncelli urinated on a copy of Duchamp's Fountain at the Carré d’Art in Nîmes. Pinoncelli reportedly attested to having added value to the work, bringing it back to life. The notion of revival by defecation seems counter-intuitive, to say the least, however, this is not the only instance of such a theory.

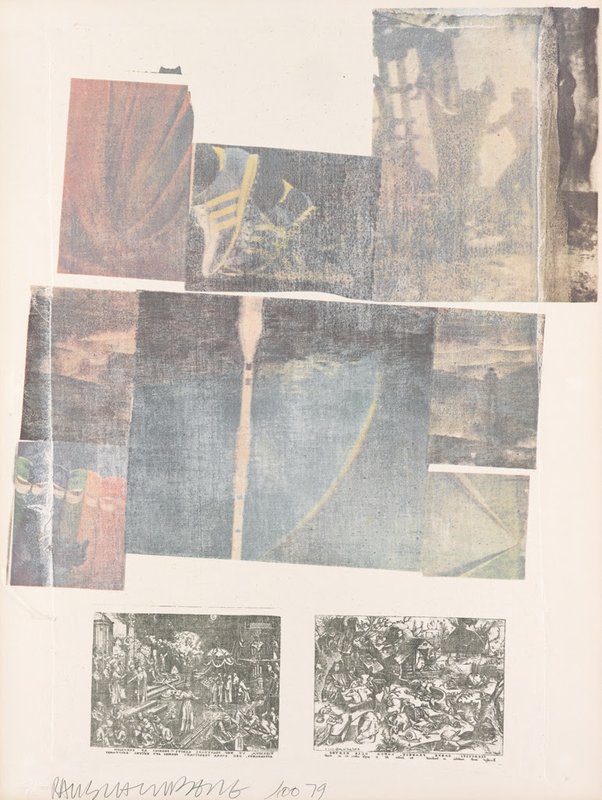

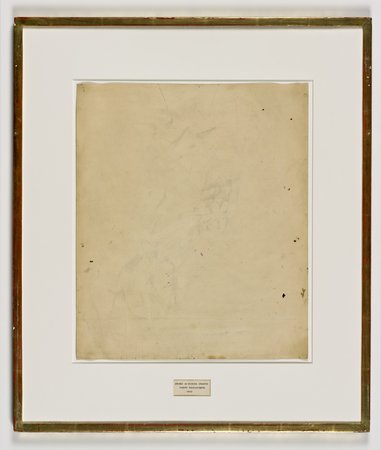

In 1953,

Robert Rauschenberg

, most known for his “Combines,” (paintings which incorporate found materials such as taxidermy and truck tires), acquired a

Willem de Kooning

drawing and erased it, re-titling the work

Erased de Kooning Drawing

. Rauschenberg’s conceptual series had begun with him erasing his own drawings; however it wasn’t long before he realized that in order for the erasure to be effective, the original work would have to be one he respected tremendously. Rauschenberg reached out to de Kooning directly, and asked for a drawing to erase, to which de Kooning surprisingly agreed.

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased De Kooning (1953), Image courtesy of SFMoMA

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased De Kooning (1953), Image courtesy of SFMoMA

The piece harkens to the cornerstone of conceptual art, Marcel Duchamp ’s readymades, which introduced the notion that the artist is first and foremost the creator of ideas. Duchamp displayed ordinary manufactured objects as his works; deemed art because of their signature and place. This caused a significant shift in the way that people thought about art.

Rauschenberg decided to do the inverse of what Duchamp sought out to do: creating an artwork through erasure rather than accumulation. The allure of Rauschenberg's piece is derived from the unseen; the ghost of what had been before. The seemingly blasphemous act or erasing a priceless work raises the question of the artist’s intent: was Rauschenberg trying to provoke? Poke fun? Destroy? Celebrate? The work can be interpreted in a number of ways, yet it is the notion of impermanence which prevails over the aesthetic of the piece.

The truth is that with art comes the art market, and as the value of a work inflates over time, the original intent of the artist is wont to be lost or convoluted. The destruction of a work by a contemporary reintroduces the artist into the art historical dialogue; both giving birth to a new movement, while also paying homage to the work's original intent. It seems paradoxical that the destruction of a work could preserve it, however a great illustration of this phenomenon is the burning of $6 million of punk memorobilia by Joe Corré, the son of fashion designer Vivienne Westwood. Though some thought the act blasphemous, the reasoning behind it was actually completely in line with the idealogies of the punk movement. After all, as writes critic Jessica Hopper, "punk in its primal form is of course a deeply anticommercial genre." Preservation of the items would display a complete disregard for what punk really was. A movement cannot stay alive forever, and thus the complete destruction of it is actually essential to the dialogue. It's up for debate; but denying people a romantic, nostalgic reckoning with these relics which had inexplicably accrued so much value over the years preserves the anti-commercial movement far more aptly than preservation.

Joe Corre burns punk memorobilia on the River Thames, Image courtesy of The Daily Telegraph

Joe Corre burns punk memorobilia on the River Thames, Image courtesy of The Daily Telegraph

Cultural values oscillate unremittingly. The only way to truly reconcile the passing of time is to keep an open dialogue with the past. Often, a reckoning with the past requires some form of destruction in order to move forward, and thus destroyed art is an important factor of the contemporary art market. In a time when art's value is largely incomprehensible, liberating a work from the stipulations of numerical abstraction for it to be seen aside from its exponential increase in monetary value; but rather for its conceptual value of representing a moment in history. To be clear, I'm not saying that you should pull a publicity stunt and punch a hole in a Pollock. (Please don't). But it is vital to remember that with blind, divine reverence comes the need for an upheaval. So there's no need to cry over spilled milk; or an erased De Kooning; or a smashed balloon dog; or a botched Jesus.