In the vein of the Guerrilla Girls , the anonymous group who in 1989 famously asked "Do Women Have To Be Naked to Get into the Met?", we've selected works depicting the female nude, dating back as far as 23,000 B.C. to as recent as 1988, exploring how the women are represented across regions and time periods.

The excerpts come from Phaidon's new book The Art Museum that features works selected from curators, art historians, and educators from across the globe, culled from hundreds of museums, galleries, and collections internationally. Imagine walking through The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Louvre, The National Gallery, LACMA, The Uffizi Gallery, the Caves at Lascaux, and The Tokyo National Museum not just all in the same day, but all from the comfort of your couch? Yes please!

------

ART OF THE STONE AGE

Room 3: Sculpture from the Ice Age

Venus of Willendorf, Gravetian Period, c. 25,000 BC Limestone with ochre coloring; H: 11cm; Image courtesy of Phaidon

Venus of Willendorf, Gravetian Period, c. 25,000 BC Limestone with ochre coloring; H: 11cm; Image courtesy of Phaidon

This rare stone example of a Venus figurine, originally colored red, comes from a campsite at Willendorf, in lower Austria. The face is looking down, the head covered by an elaborate hat.

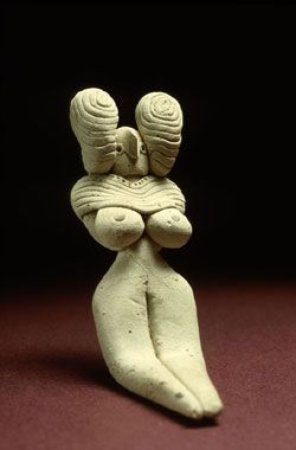

SOUTH ASIA

Room 209: The Harappan Culture: Ancient Civilization in the Indus Valley

Female Figurine, c. 5500-2400 B.C., Terracotta; Image from Wikimedia

Part of the Neolithic 'mother-goddess' tradition, this figurine's abundant breasts and hips suggest links to fertility and procreation. Her hair was probably painted black; brown ochre would have covered the body, and her necklace was probably yellow. Her seated posture, with arms crossed under the breasts, is common throughout the region, as is her extravagant hairstyle.

ANCIENT GREECE

Room 41: Hellenistic Sculpture and Portraiture

Aphrodite, Eros, and Pan c. 100 B.C., marble; Image courtesy of The National Archeological Museum in Athens

Aphrodite, Eros, and Pan c. 100 B.C., marble; Image courtesy of The National Archeological Museum in Athens

Aphrodite, goddess of love, with her left hand shielding her pudenda, playfully threatens the demigod Pan, while her son Eros flutters overhead. The sandal is an allusion to lovemaking, for ancient erotic scenes often depict slapping with sandals as a form of sexual stimulation.

ANCIENT

ROME

Room 59: Adaptation and Imitation in Roman Sculpture

Capitoline Venus, 2nd century ad; marble; H: 6 ft. 4 in.; Image Courtesy of Musei Capitolini

Capitoline Venus, 2nd century ad; marble; H: 6 ft. 4 in.; Image Courtesy of Musei Capitolini

This statue of Venus (Aphrodite) caught nude in her bath is based on the first major nude representation of the female body in Greek art, a statue carved by Praxiteles in the fourth century bc.

ITALIAN RENAISSANCE

Room 174: Fifteenth-Century Venetian Painting

Giovanni Bellini, Woman with a Mirror, 1515; oil on canvas; Image from Wikimedia

Giovanni Bellini, Woman with a Mirror, 1515; oil on canvas; Image from Wikimedia

Depictions of beautiful naked women became a popular Venetian genre in the sixteenth century, commissioned by male patrons for their private chambers.

NORTHERN RENAISSANCE

Room 207: Northern Renaissance Artists and Italy

Jan van Scorel, Death of Cleopatra c. 1523, Oil on panel; Image Courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Van Scorel (1495–1562) was mesmerized by the sensuous paintings he saw in Venice, especially depictions of beautiful nudes in lush landscapes. This painting of Queen Cleopatra shows in its composition, colors and loose brushwork how thoroughly van Scorel absorbed Venetian art, particularly that of Georgione.

BAROQUE AND ROCOCO

Room 248: Sex and the Counter Reformation

Artemisia Gentileschi, Venus and Cupid, c. 1625–27; Oil on canvas

Artemisia Gentileschi, Venus and Cupid, c. 1625–27; Oil on canvas

The subject of nudity was a fraught one in the seventeenth century. On the one hand, continuing fascination with Classical antiquity encouraged artists to depict the nude; on the other, Counter-Reformation writers warned against what they saw as indecency and lustfulness in art.

The trial of Agostino Tassi for the rape of Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1652/53), combined with her paintings of female violence against men and female nudes, have prompted feminist interpretations of her work. Works such as this, however, appear to have been tailored to the taste of male patrons. The strong chiaroscuro and the pose, based on Caravaggio’s Sleeping Cupid (c.1608), demonstrate the continuing influence of that artist’s style.

[related-works-module]

ART OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Room 287: Orientalist Painting

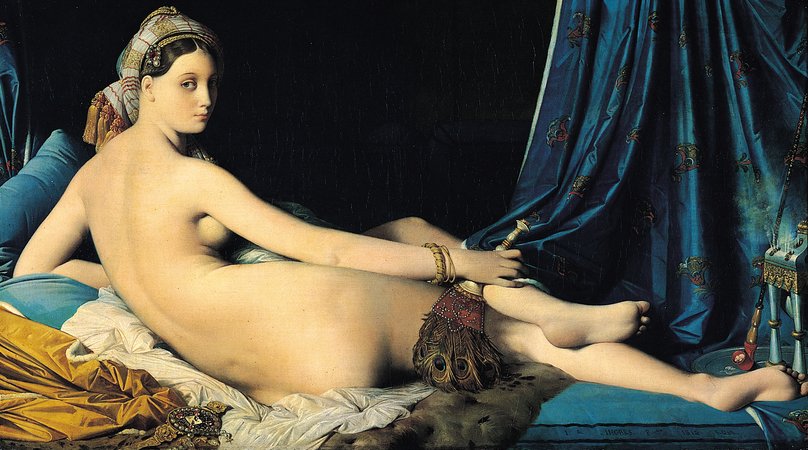

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, Oil on canvas; Image Courtesy of the Louvre

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, Oil on canvas; Image Courtesy of the Louvre

With its richly exotic furnishings and latent eroticism, Ingres’s (1780–1867) nude conjures up the Western ideal of the harem woman (‘odalisque’). The influence of Mannerism on Ingres’s style is evident in the long, sinuous lines of the body and the illustionistic details of the setting, and the work attracted fierce criticism for its anatomical inaccuracy when it was exhibited at the 1819 Salon.

Room 296: The Nineteenth-Century Body

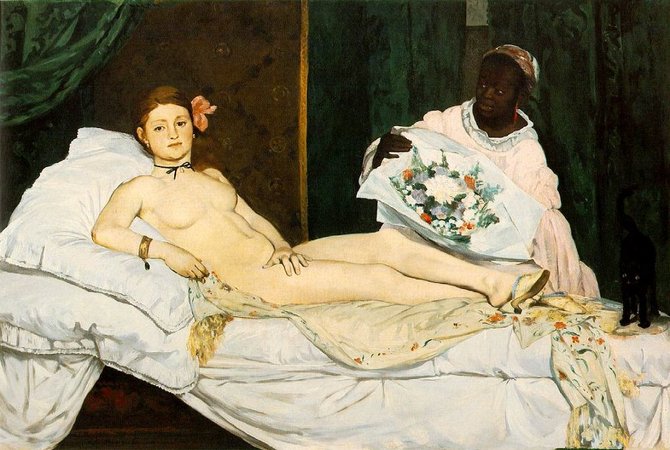

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863; oil on canvas; Image Courtesy of Manet.org

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863; oil on canvas; Image Courtesy of Manet.org

Over the course of the nineteenth century, depiction of the nude in painting and sculpture underwent a significant shift, both stylistically and conceptually, away from a classicized, idealized body. Female figures predominated, engendering debate about the purpose of art and its use in defining social space and social mobility, as well as prompting anxieties about sexual mores and gender roles.

For artists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the work of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was one of the most important models for representing the female nude. The opposition of Western and non Western bodies in his Orientalist fantasies were re-imagined as a contemporary courtesan and her servant by Édouard Manet in Olympia , painted in 1863. The female nude predominated in the 1860s: there were so many at the Salon of 1863 that the writer Théophile Gautier dubbed it the ‘Salon of Venuses’. It was against this backdrop of the pristine Venus that Manet’s Olympia , exhibited in 1865, was castigated for its deviations from the established formula.

The succès de scandale of the 1865 Salon, Olympia has become an icon of modernism for its perfunctory modelling, visible brushstrokes and flatness. Based on Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538), this painting by Manet (1832–83) scandalized viewers as much for its deviations from accepted standards of finish and bodily proportions as for its frank portrayal of sexual commerce, highlighted by the figure’s coolly appraising gaze and emphatically placed left hand, the only area given a full gradation of tone.

AFRICA

Room 314: Central Africa

Nio Bieri, 19th-20th centuries; wood, metal, and oil patine; Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This powerful female form was made to guard ancestral relics of the Fang people. Her muscular build attests to her ability to combat supernatural threats. She was placed on a cylindrical bark box that held ancestral skulls and long bones. This piece once belonged to Fauve painter André Derain and sculptor Jacob Epstein.

ART FROM 1900 TO MID-CENTURY

Room 330: Picasso and Braque; Cubist Painting

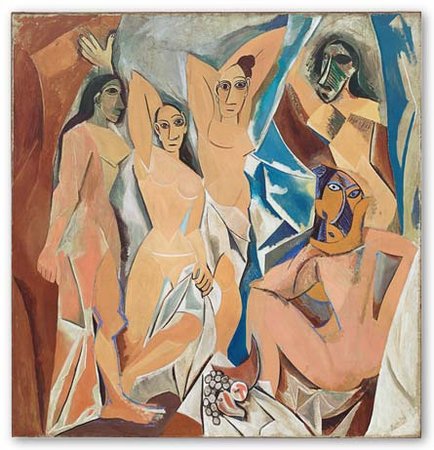

Pablo Picasso Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907; Image courtesy of MoMA

Pablo Picasso Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907; Image courtesy of MoMA

This canvas shocked even the most forward-thinking of Picasso’s friends. Earlier sketches show the composition in landscape format, with a sailor in the background, implying a brothel setting. The final composition teeters between a theatrical scene, with the woman at the left seeming to draw back a curtain, and an undecipherable combination of still-life, nudes and indefinable interior. If the painting is read as a brothel scene, Picasso’s removal of the male figure seems to implicate the viewer as client. This canvas exemplifies the notion of primitivism as possessing a savagery and uncivilized abandon that artists found both exciting and liberating.

ART SINCE THE MID-20TH CENTURY

Room 401: Body and Performance Art

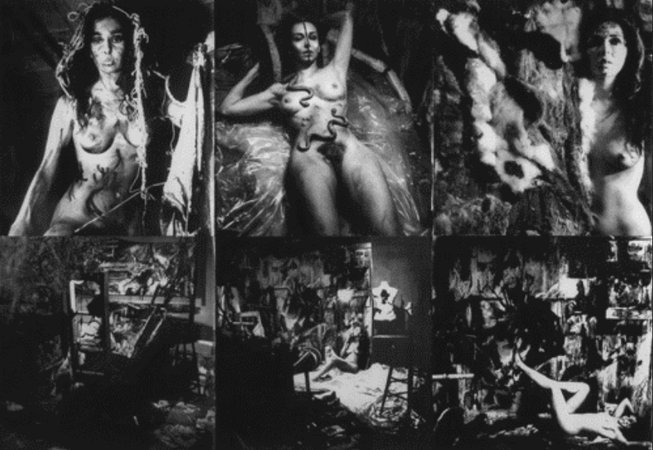

Carolee Schneemann, Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions, 1963; performance; Image courtesy of the artist

Carolee Schneemann, Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions, 1963; performance; Image courtesy of the artist

Schneemann’s (b. 1939) Eye Body is unusual among her feminist works because it focuses on the eroticism of her body, rather than lamenting its treatment at the hands of men. In a series of transformative actions, including covering herself in paint, grease, chalk, fur, feathers and garden snakes and ritually dancing around her loft space, Schneeman retakes control of her body from the male gaze. With a background in painting, she undertakes this work to further this association and infuse herself in her medium. The work was photographed by Icelandic artist Erró.

Room 411: Identity Art; Race in a Post-Colonial World

Yasumasa Morimura, Futago, 1988; chromogenic print with acrylic paint and gel; Image courtesy of SFMoma

Yasumasa Morimura, Futago, 1988; chromogenic print with acrylic paint and gel; Image courtesy of SFMoma

Yasumasa Morimura (b. 1951) integrates himself into the Western artistic canon by appropriating its works with himself in the starring role. Here, Morimura creates an ironic parody of the traditional female nude. Taking the role of both Olympia and her black servant, Morimura alludes to these different identities within the artist through the work’s title, meaning ‘twin’. References to his nationality, including the kimono on which he lies and the maneki cat (a type of Japanese mascot), further align his own identity with the art historical tradition.

[related-works-module]