Talking about contemporary art ain't easy—it's a language of many dialects, secretly freighted words, and voluminous assumptions packed into seemingly innocuous phrases. To negotiate these linguistic shoals, here’s the second edition of our “Survival Guide for Talking About Contemporary Art” series, looking at some of the tricky terms used by curators, artists, critics, and other art muckety-mucks today.

"ART WORLD" (ärt wərld)

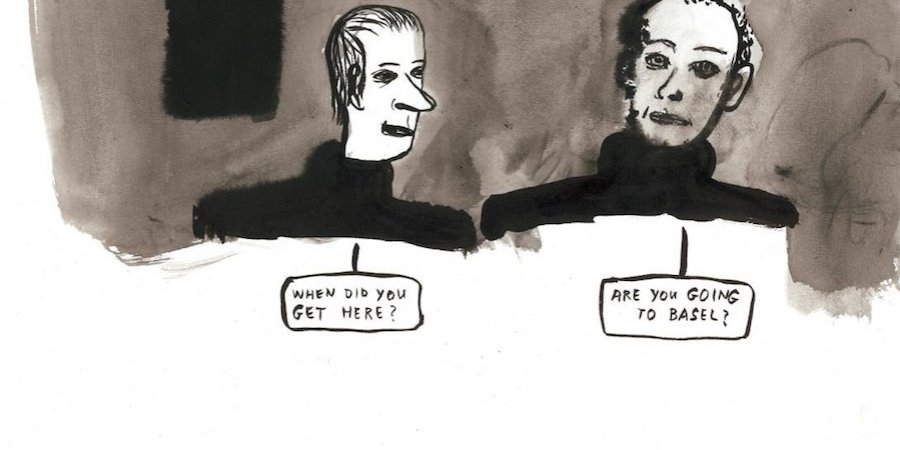

“Art world, music business. What does that tell us?” quips a Venice Biennale partygoer in Geoff Dyer's novel Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi. The eponymous Jeff doesn’t give the comment much thought—he’s too busy observing the art-world codes and customs himself at its epicenter, swilling back bellinis amid the pandemonium of the vernissage. But baked into the term "art world" are a complex network of social and theoretical factors that deserve some examination.

Originally, the term had nothing (or at least little) to do with parties—in fact, it marked a radical new philosophical paradigm. The late critic and academic Arthur Danto coined it in a 1964 essay in the Journal of Philosophy called “The Artworld,” written after seeing Andy Warhol’s Brillo box at New York’s Stable Gallery and asking what distinguished this particular soap box from any other old soap box.

His answer did nothing less than challenge 2,000 years of Platonist thought that defined art as mimetic. Artworks, Danto said, take on properties in relation to a parallel world of art—"an atmosphere compounded of artistic theories and the history of recent and remote paintings"—whose denizens can locate a work within a linneage invisible to the uninitiated. In other words, where the ordinary viewer might not be able to see the difference between the two Brillo boxes, those in the artworld know it. "The artworld stands to the real world in something like the relationship in which the City of God stands to the Earthly City," Danto wrote. Well, then.

In the following decades, the term caught on with anthropologists like Howard Becker, who separated "artworld" into two words and described it as a complex subculture built around contemporary art. In 2007, Sarah Thorton’s ethnography, Seven Days in the Art World, likewise defined it broadly as a cultish league united by a “belief in art,” composed of many separate pieces moving together as a giant sorting mechanism. But in truth, the way the term "art world" is employed most commonly today is far closer to the way Jeff's interlocutor in Venice uses it: to describe the social milieu inhabited by people connected to the art business, be it through art-dealing, collecting, journalism, curation, or the like.

So why "world" rather than "industry"? Simple: because the art business is so small, relative to other sectors of its profitability, and because so much of its unregulated business is governed by handshake deals and mutural understandings, the social factor is dramatically pronounced. The same people will see each other at the same art fairs, parties, shows, and other events year after year, so a premium is placed on comity—something that leads to an echo chamber of consensus around which art of the moment is hot ("That Brillo box is AMAZING") and what is not ("Painting is dead"). As a result, whenever a critic strikes with a bad review, or, better yet, some (often anonymous) acid-tongued contrarian emerges—like ICallB on Instagram these days—it immediately becomes the talk of the town.

At the core of this network, Danto's definition holds strong: placing a Brillo box in a gallery defines and groups those who understand it as art in the same way that Wallace Stevens's jar situates the slovenly Tennessee wilderness surrounding it. Outsider artists are "outsiders" precisely because they aren't in the art world—they're on their own separate wavelength, both socially and, often, theoretically. Ironically, members of the art world are often themselves seen as outsiders from society at large. But no surprise there: the very brain-stretching complexities embedded within the term "art world" guarantee that its citizens are a bunch of weirdos.