The self-portrait is such a common feature of art that it's surprising when one considers how old the format is: it was just five hundred years before Ai Weiwei beamed his first contemplative Instagram selfie around the world that painters of the Renaissance began to experiment with the approach, turning their gaze away from religious figures and royals to depict their own not-so-humble selves. The birth of the self-portrait is partially owed to the humanistic ideas that shaped the Enlightenment, elevating individual secular experiences into subjects worthy of art—but a more pragmatic development is also responsible, namely the proliferation of cheap mirrors that made it easy for artists to paint the most readily available sitters in their studio, themselves.

Soon, self-portraits became a fashionable staple of the artist’s practice, allowing painters to advertise their own unique sensibilities and stances. From Albrecht Dürer’s intensely naturalistic self-portraits to less overt infiltrations of larger canvases—such as Jan van Eyck’s sneaky appearance in the convex mirror of The Arnolfini Wedding, or Raphael's sly cameos in his Sistine Chapel frescos (as a hard-working scribe in the Athenian agora, for instance)—images of artists began popping up everywhere.

Today artists continue to reinvent the self-portrait, often through similar gradations of brash self-promotion and subtle disguise. In fact, several of today's artists make the format the core of their work. So why is self-portraiture still relevant today? To answer that, here's a guide to a few of the most important themes in contemporary self-portraiture.

BARING IT ALL

Martin Kippenberger's Self-Portrait (1988)

Martin Kippenberger's Self-Portrait (1988)

Though Tracey Emin never herself appears in her controversial readymade My Bed, it would be hard not to feel Emin’s presence when looking at that disheveled found sculpture of her debaucherous mattress: with used underwear, liquor bottles, and stubbed cigarettes lining the bed, it’s obvious that the artist is using the intimate setting as a confessional. In that way, it is a quintessential self-portrait of regret and despair, much like Picasso’s painting of his own grieving visage from the Blue Period. The tell-all self-portrait was also a favored genre of the hard-living German painter Martin Kippenberger, the even-harder-living British painter Francis Bacon, and the legendary Frida Kahlo—each of whom adopted the warts-and-all mercilessness of prior masters like Rembrandt and van Gogh. More recently, artists like Nan Goldin have transferred this tendency to photography, creating diaristic reports from the front lines of life that are often shocking in their raw, self-exposing truths.

A TOOL OF SUBVERSION

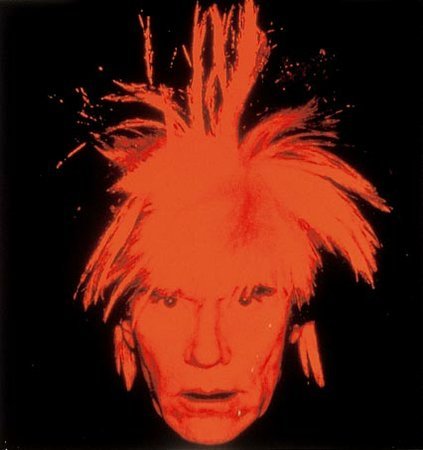

Andy Warhol's Self-Portrait (1986)

Andy Warhol's Self-Portrait (1986)

Self-portraiture has become a respected art-historical genre unto itself—which is perhaps why so many contemporary artists have felt inclined to make it a target. In his famed fright-wig self-portraits, Andy Warhol screen-printed his own image—a flat, quick portrait, closer to currency than one of Dürer’s richly detailed paintings—in such volume that it ate away at the notion of himself as an individual, stripping him of his aura of artistic genius and rending him the equivalent of a Campbell’s Soup can, Coca-Cola bottle, or other consumer good. (A cheap good as well, since at the time the work's many editions lowered its value; today, though, these fetch staggeringly high prices.) Since Warhol’s time, artists have continued to undercut the tradition of the self-portrait, such as in Jeff Koons’s provocative Made in Heaven series that featured pornographic images of him and his wife— questioning the nature of artistic taste—and Cindy Sherman's continuing series in which she uses prosthetics to jarringly insert herself into famous portraits from throughout art history. Deborah Kass, meanwhile, brings this approach full-circle back to Warhol, painting herself in the style of the Pop artist's fright-wig paintings.

PLAYING DRESS-UP

Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Still #14 (1978)

Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Still #14 (1978)

It's ironic—sometimes contemporary self-portraits barely count as images of the artists themselves. In the work of photographic practitioners like Sherman, Kalup Linzy, Liz Cohen, Michael Smith, and Xaviera Simmons, the work is less a portrait of the artist him- or herself than it is of a fictional character embodied by the artist. As one of the most influential self-portraitists of this type, Sherman alters her appearance to enter female archetypes from pop culture and other arenas, partially in an effort to explore notions of originality. In the hands of such artists, the self-portrait becomes a way to transcend social boundaries—as in the case of Collier Schorr's gender-hopping photographs. Like the subversive approach above, such work has much in common with appropriation art, and shares similar goals.

PORTRAITS OF PERFORMANCE

Ana Mendieta's Imagen de Yagul (1973)

Ana Mendieta's Imagen de Yagul (1973)

With the rise of interest in performance art in the 1970s, many artists began to incorporate elements of performativity into their self-portraits—sometimes documenting staged performances as they occurred, in the cases of Marina Abramovic and Vito Acconci, and other times putting themselves into performative situations that had an audience of one: their camera. In an example of the latter approach, the land artist Ana Mendieta became one with the earth for her Silueta series of photographs and performances, elaborately camouflaging herself in natural settings. Francesca Woodman, meanwhile, incarnated various psychological states in her haunting, intimate photographs that investigate the relationship between time and place. Artists have also used combinations of performance and self-portraiture to achieve political aims. Hannah Wilke’s feminist photographs, for example, included photographs of her nude body dotted with pieces of gum—chewed and shaped into crude, tiny vaginas—as a form of objectification.

THE ARTIST AS OUTSIDER

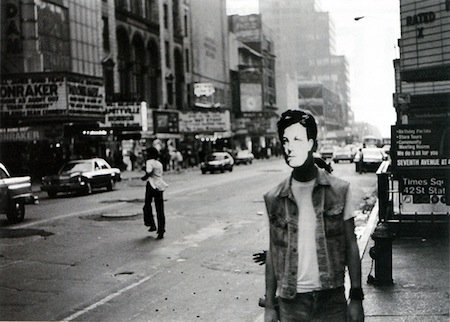

One of David Wojnarowicz's self-portraits as Rimbaud

One of David Wojnarowicz's self-portraits as Rimbaud

Especially poignantly, self-portraiture has been a riveting genre for artists to express their difference from the rest of society—oftentimes, a society that utterly rejects them. David Wojnarowicz's masked self-portraits as the questing boy-genius poet Rimbaud wandering through the seedier streets of New York in the grips of the AIDS crisis are filled with both anger and pathos; Robert Mapplethorpe's astonishing portraits of himself in uncomfortable S&M-derived positions (including one notable nude example with a bullwhip protruding from a sensitive place) doubles down on the stereotype of homosexuals as frightening outsiders. Similarly, Catherine Opie photographed herself with a childish doodle of a happy family's home cut into her body while she wore bondage gear to explore what it means to be “normal.”