The Brooklyn-based sculptor and installation artist Rachel Harrison is one of the few artists working today able to integrate the seismic 20th-century artistic innovations (think appropriation, readymades, and a general post-medium approach) into her work in a way that moves these gestures beyond winking conceptualism and into the realm of formal elegance.

Her work has been described as “both the zestiest and the least digestible in contemporary art” by The New Yorker’s art critic Peter Schjeldahl, and the characterization seems to hold up no matter which section of her oeuvre you choose to delve into, from her Styrofoam and found object sculpture to her searching, sensitive photography and even her more recent collaged pieces, messy and striking takes on the old Modernist technique.

In this essay, excerpted from Phaidon’s Defining Contemporary Art, the famed Swiss curator and art historian Bice Curiger describes the subtle historical and aesthetic qualities of Harrison’s seminal 2007 installation Voyage of the Beagle.

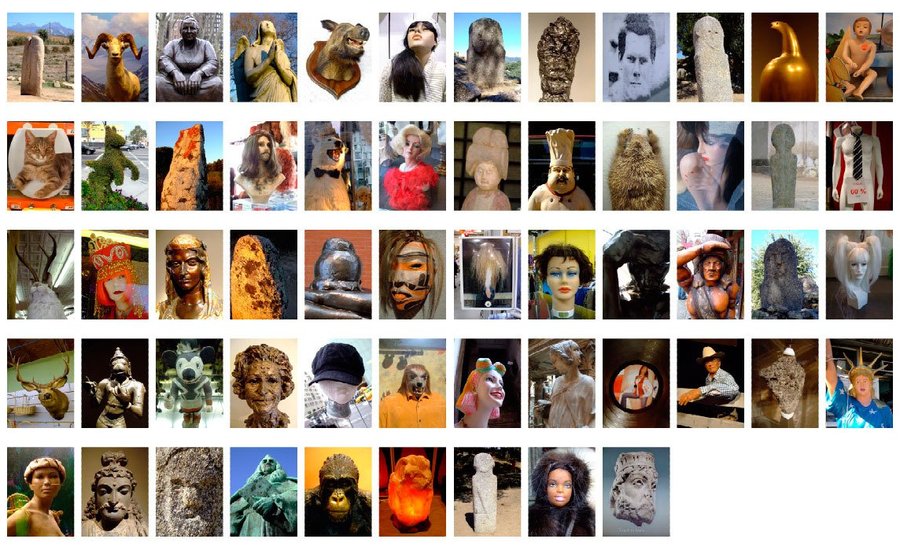

Installation View, Migros Museum, Zurich, 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

Installation View, Migros Museum, Zurich, 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

A certain irony is at work in Rachel Harrison’s titling of her programmatic photo series Voyage of the Beagle. It refers to the journals, published in 1839, from Charles Darwin’s second expedition on the HMS Beagle, a journey that would inspire his pivotal 1859 text On the Origin of Species. But every part of Harrison’s oeuvre seems to counter any notion of an evolutionary approach to art history or culture. She delights in mixing together all manner of disparate elements and cultural-historical references in her sculptures and photographs, colliding ideas and imagery from around the globe and across the centuries.

Comprising 57 photographs installed in a single horizontal line, Voyage of the Beagle is a record of Harrison’s own expedition in search of the origins of sculpture. Her voyage began with a trip to Corsica, where she saw prehistoric menhirs—mysterious standing stones dating back to 1500 BC that feature carved designs of stylized human figures. From there she travelled across Europe and the United States, photographing a dizzying array of found human and animal forms in venues that ranged from museums to pizza parlors—grandeur and solemnity clashing with the shallow emptiness of consumer culture.

Captured by her lens are mannequins, prehistoric sculptures, taxidermy animals, a public sculpture of Gertrude Stein, cemetery angels, tribal masks, topiary and likenesses of pop-culture celebrities such as Beyoncé Knowles and Kevin Bacon. Sculptures from the history of art also feature, including an ancient Janus figure, as well as modernist classics such as Rodin’s Burghers of Calais (1884-88) and Brancusi’s Bird in Space (1923). The resulting heterogeneous, even sacrilegious, collection of photographs is hung edge-to-edge in a carefully specified non-chronological order, a strategy of visual leveling that forces us to search out connections from one image to the next, confronting and contemplating the human form as our ancestors have done for thousands of years. Similar strategies are seen in Michael Schmidt’s EIN-HEIT (U-NI-TY, 1991-94) and Gerhard Richter’s Atlas (1962-present), both of which are important precedents for Voyage of the Beagle.

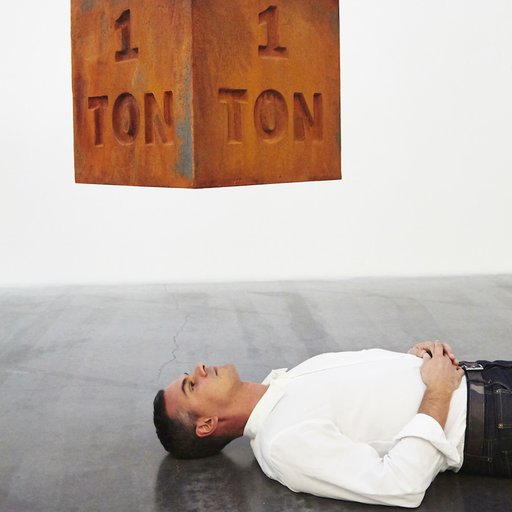

In 2007 Voyage of the Beagle was featured in an exhibition of the same name at the Migros Museum in Zurich. There it was juxtaposed with a selection of Harrison’s sculptures, which are inextricably informed by this salient photographic index. Evincing a peculiarly American approach to sculpture, these gnarly, totemic structures – made from, among other things, polystyrene, wood and cement – not only provide bodies for the many heads seen in Voyage but also form part of Harrison’s wider analysis of the inception and evolution of monuments and statues. Their titles refer to well known male figures, including Johnny Depp, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Fats Domino, while their monument-like forms suggest endless associations with popular culture, art history and a multitude of historical examples, from ancient Egypt onwards.

Compared to other sculptors of her generation, such as Rebecca Warren, Harrison’s approach is far less sensual; her interest lies more with the final grotesque amalgam of materials and imagery. Claude Lévi-Strauss (2007), for example, comprises a pair of variegated obelisks resting on cardboard boxes that support a taxidermy hen and rooster; in Johnny Depp (2007) a towering fusion of assorted bric-a-brac has been painted gold and purple and embellished with a gold hoop earring. Rauschenberg’s combines are pertinent here, as are their Dada and Surrealist precedents, such as Kurt Schwitters’ Zweite Merzsäule (Second Merz Column) (1923).

But sculpture for Harrison is primarily monumental, and, unlike most of her peers, her sphere of reference—as mapped out so astonishingly by Voyage of the Beagle—transcends recent art history, reaching to the furthest recesses of sculpture’s primarily figurative past. Thus Voyage of the Beagle proposes a wholly different foundation on which representation can be sited.