Millennials are often derided for their supposed disconnect from reality, or their over-connection to their phones. But Phaidon's Vitamin P3 proves that these digital natives also provide new ways of looking at—and painting—people. The excerpt below explores the work of three international portraitists—Hayv Kahraman, Hulda Guzman, and Ewa Juszkiewicz—who each draw on their distinct cultural contexts and the rich history of portraiture to create works that are near-classical in form but radical in content.

HAYV KAHRAMAN

Born 1981, Baghdad, Iraq. Lives and works in Los Angeles.

Bab el Sheikh, 2013

Bab el Sheikh, 2013

Hayv Kahraman’s paintings are a refined confluence of cultures, an “otherworld” where different pictorial traditions meet, and every picture tells a story. Intensely personal, her paintings are concerned with understanding the politics of tradition and gender. Born in Baghdad in 1981 during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88), Kahraman spent her formative years in exile. Her journey as a refugee began aged eleven when she, her mother and sister travelled from Iraq on false passports through Ethiopia, Yemen, and Germany, finally settling in the far north of Sweden (where her father joined them a year later). She began to paint at the age of twelve and went on to study art and design in Florence, after which she returned to Sweden to take a degree in web design. Without doubt her aesthetic has been shaped as much by her émigré status in Europe, and now America, as it has by her natural gift for graphics.

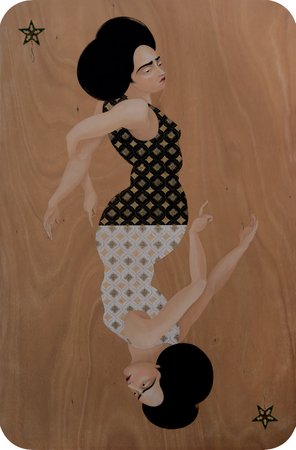

Kahraman’s early works range in their references from Japanese sumi-e painting, Arabic calligraphy, and Art Nouveau. Brutal images of rape, suicide, and murder are particularly unnerving when executed with the delicate, light stroke of brushed ink. Painting has become Kahraman’s place of protest (as much as it is her salvation). Women—grieving mothers, displaced and alienated girls—take centre stage in her pictures which represent, and therefore advocate for, those silenced by their gender, oppressed by politics, or, through no fault of their own, caught up in the consequences of war. Migrant 11 (2009) quite literally reveals, in a reversed mirror image, the “double consciousness” of an individual whose identity is divided: her arms free on the one side, and on the other contorted and twisted into a knot behind her back. Skillfully combining abstraction with figuration, these stylized figures (crafted from three-dimensional scans of Kahraman’s own body) are symbols of the “every woman.” In Bab el Sheikh (2013) the metaphor of the mashrabiya (a type of oriel window traditional in Arabic architecture) is incorporated not only as an aesthetic device to arrange Kahraman’s characters in a rhythmic conversational style, but also to recall its dual purpose: to provide shelter or to imprison. In Her Name is Gun (2015), tessellated, geometric patterns—recognizable in Islamic art—serve to structure the painting. Centrally placed on raw untreated canvas (specifically sourced by Kahraman for its hue), these idealized women seem to be as influenced by Sandro Botticelli’s Renaissance Venus (1484–86) as by the twelfth and thirteenth-century manuscripts of the Baghdad school of miniature painting.

Kahraman’s canvases absorb tradition, but with a knowing interpretation that is both personal and political. Intra-cultural synergies exist in a mix of historical and traditional elements and each painting is conceived and imbued with a sense of story—character, plot, situation, conflict, and resolution—more commonly associated with theatre, cinema, or literature. As if to confirm this impression, in her most recent works such as Local Game and Magic Lamp (both 2015), Kahraman has included “subtitles” on her paintings, written in the calligraphic naskh (a fluid script, often used to comment and transcribe the Quran). Such texts act as extended captions to the paintings themselves.

– Grainne Sweeney

HULDA GUZMÁN

Born 1984, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Lives and works in Santo Domingo.

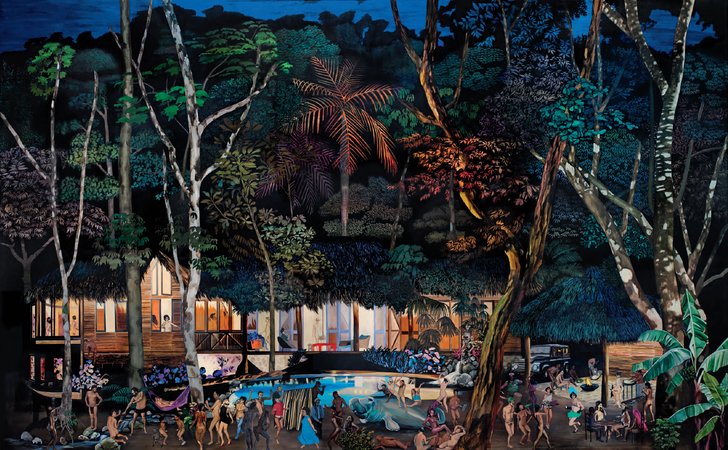

Influenced by the rich symbolism of Mexican altarpieces and the naively inventive ex-voto paintings of Mexican folk art, Hulda Guzmán is a storyteller. Her large acrylic paintings document everyday life—swimming, picnicking, dancing, fornicating and socializing—drawing upon her Caribbean birthplace, the Dominican Republic. Look, for instance, at Fiesta en el Batey (2012). Revelers (semi-clad or naked) dance, frolic, lounge and cook under a majestic canopy, which consumes the picture. The exquisite details of the painting, together with Guzmán’s use of deep blue, purple, green and crimson, create a carefully constructed world, giving the impression that we, as viewers, have stumbled upon a secret night-time celebration. There is perhaps a gentle nod to the genre paintings of the Dutch Renaissance painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1525–69), too—notice the figures riding the unamused manatee—hinting at a moral subtext. Moving from left to right, these individual figures of island life, bathed in the soft glow from the wooden shacks, are united in their celebrations and yet seem somehow disconnected from each other.

In her paintings of interiors, Guzmán is more economical with her composition. Take, for instance, Anne in her Bath (2013), where contemporary characters enact their desires or relax in a style that borrows from Japanese erotica painting (shunga). Here, history is duped and re-written, and tradition is given a contemporary twist by including tropical landscapes or modernist interiors. The architecture and décor of these rooms are essential in creating an enticing and natural arena for these intimate moments. Plants, record players, rugs, iconic chairs, and large windows with an omnipresent view are strategically arranged. As viewers, we are drawn into the detail, complicit in Guzmán’s voyeurism, seeing inside these homes uninhibited passion and abandonment, which seems to be more natural than ribald.

Fiesta en el Batey, 2012

Fiesta en el Batey, 2012

Most of these interiors are painted on wood, with the erotic narrative depicted delicately on the surface. The textured veins of the wood create turbulent skies or metamorphose into the sides of a mountain or an ellipse of a carpet, as seen in Dynamic Relaxation (2013). Such paintings, with their restraint and flatness, create harmonious interiors that allow us to consider our own perhaps messy and complex lives. Guzmán has also explored more gestural painting, in which she uses free and loose lines and unconventional colors. Normally right handed, she uses only her left hand to create a series of portraits and landscapes in a single sitting. In setting these parameters Guzmán makes paintings that are instantly evocative and emotive, allowing her to extract only the essence from her subjects or scenes, including herself. In Self-Portrait (2013) we see the artist as pure expression. She looks out at us with a stern, unflinching gaze, seemingly needing nothing from us.

– Leila Hasham

EWA JUSZKIEWICZ

Born 1984, Gdansk, Poland. Lives and works in Warsaw and Krakow, Poland.

Ewa Juszkiewicz adopts the visual conventions of portraiture but drags them into the present, altering and denaturing the codes and prompting us to consider the cultural afterlife of such images. Be it through a portrait re-interpreted or a lost artwork re-crafted, from the eighteenth century portrait painter Joshua Reynolds (1723–92) to the modernist Paul Klee (1879–1940), her uncanny paintings upset the hierarchies of cultural memory, inserting the hybrid and the strange into the historical order.

Since 2012, Juszkiewicz has created a series of paintings based around portraits of women: mothers, wives, and daughters. These images are, in a sense, portraits of significant others, however it is the maligned status of these women relative to their associated male counterpoints (who are not represented) that becomes significant. Portraiture of course has seldom been solely about its subject but interlaced with social conventions, status and covert (or not so covert) symbolic messages. This begs the question: how does an artist begin to negotiate the history of the objectification of women in portraiture? If history has rendered these individuals unremarkable, Juszkiewicz’s act of re-painting them both extends this act of negation whilst also transforming these characters into extraordinary, surreal apparitions of their former selves.

Make-up and hairstyles are fundamentally costumes of the face: under the aegis of style they embellish, conceal, and frame, just as in the original portraits the painted face stood in accord with principles of decorum. Yet in wholly stripping it away, replacing appearance with masses of foliage, cloaking features within folds of fabric or masking expression beneath crustaceans, Juszkiewicz does not hide the figure nor undermine its status, but rather creates alternative, freely-imagined and fantastical portrayals of women. Juszkiewicz’s act of feminist appropriation importantly offers no possibility of atonement; the injustices of history can now not be undone. What is born instead is a new story; a future history for the paintings’ anonymous—and more often than not nameless—protagonists.

More recently Juszkiewicz‘s interest in the historically destitute image has expanded to reworking images of artworks that have been lost, destroyed or irrevocably damaged. Rejecting the possibility that these artworks are irretrievably gone, relying on the mimetic possibility of poor-quality reproductions in books or the fragments of anecdotal recollections, Juszkiewicz uses the act of painting to engender a point of return for these languishing memories. In her re-interpretative paintings it may be but an aura of the past that is rejuvenated, but a memory is rekindled, an image endures.

In his 1940 essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin proposed that we recognize the past, not as it once was, but that we “seize hold of a memory as it flashes up” in the present. Having traipsed through hoards of images in the proverbial archives of art history, those that Juszkiewicz has chosen to paint are those that trigger associative memories and find unknowable resonance. In working from imprecise black and white reproductions, Juszkiewicz is spared the burden of authenticity; she is free to shape these artworks, and color these memories, as she sees fit.

– Matthew Hearn

[related-works-module]