Phaidon’s new Vitamin P3 is a global compendium of painters emerging and worth knowing, so we’ve decided to show off our favorites from Latin America. Hailing from Peru, Brazil, and Argentina and working within their own highly distinctive styles, these artists offer just a taste of the artistic diversity of the region, and three more reasons to remember that "American" art doesn't stop north of the Rio Grande.

SANDRA GAMARRA

Born 1972, Lima, Peru. Lives and works in Madrid.

Peruvian-born Sandra Gamarra is known for producing paintings that copy other artworks or museum displays. In the Latin American context, translation and copying are an essential part of igniting the memory of an object, translating the past as it is recovered in the present. As Gamarra describes, “without copy there is no original.” She is interested in the processes of memory and the way in which objects play a role in capturing and maintaining memory. Her practice examines the mechanisms within exhibitions, institutions, and visual modes of art distribution that become metaphors for the construction of individual identity. As she has stated, the aim is “to hide, expose, reflect, and alter assumed structures.”

Gamarra has a broad repertoire of source material including images of contemporary art alongside press photography and pictures of classical art. Within her paintings, she brings together a variety of sources and presents them in a manner that is museological in its appearance. For example, school children are depicted in monochrome, kneeling and sitting with pencil and paper, drawing what they see. Museum visitors are depicted in relation to museum objects, their bodies as much forms for contemplation as the artworks depicted, as in In Order of Appearance IX (2012). In other works, the art objects themselves have been reproduced, recalling the likes of Josef Albers’ square compositions, Yinka Shonibare’s headless figures, Giovanni Anselmo’s concrete and lettuce forms, Erwin Wurm’sHouse Attack (2006) and Alexander Calder’s suspended sculptures, among others.

Gamarra’s brushwork is delicate and precise, resulting in what appear to be hyper-real collages. The effect is to give a blurry identity to objects or images that we may feel we know well—a gentle prod to reassess how we approach such things by weaving new narratives around them. Gamarra’s influences include Elaine Sturtevant (1924–2014) and her sole use of the copy as a “generator of originals.” The quiet paintings of Agnes Martin (1912–2004) are also a point of reference, with the documentation of artworks being copied as an attempt to translate photography to painting; for Gamarra, this exercise becomes a meditation on suspending personal subjectivity. Writers who have translated other authors are a further source of inspiration, including the likes of Argentinian novelist Julio Cortazar or the German lyric poet, Friedrich Hölderlin.

While her earlier work looked at art museums as places for worship or contemplation—in the vein of cathedrals or pilgrimage sites—and artworks as objects of faith, her recent works, such as Deposit III (2015), give more importance to painting as an actual object in its own right: “It allowed me to leave bi-dimensionality, unhang [painting] from the wall and naturally add other supports of images (video, mirrors, printed matter, found paintings) and link them to a same genealogy.”

– Louisa Elderton

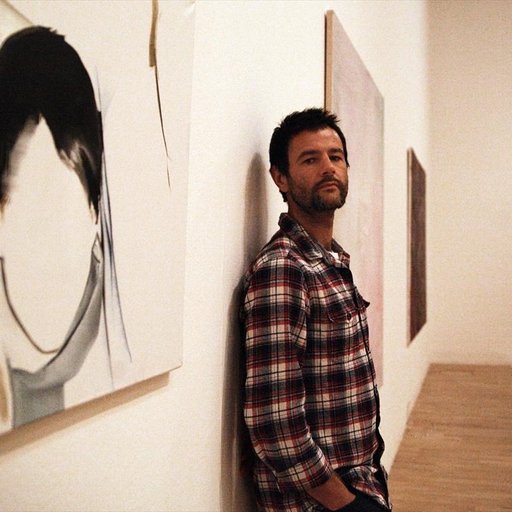

JUAN JOSÉ CAMBRE

Born 1948, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

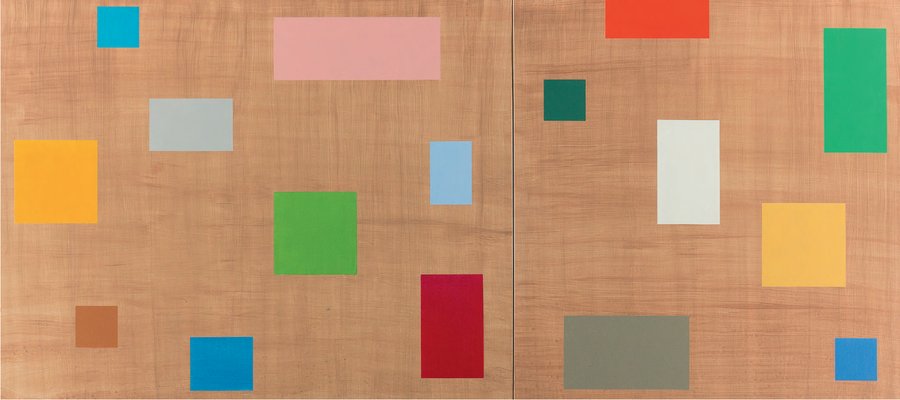

Un Bárbaro en las Sierras, 2015

Un Bárbaro en las Sierras, 2015

For more than forty years, Juan José Cambre has been obsessed with paint and its immediate possibilities in terms of texture, color, and representation. His practice, a stubborn vocation, is grounded in an historical acknowledgement of the medium’s variations across times and territories. In the beginning, this need to paint offered so many possibilities in brush strokes and layering that Cambre was lost in a world of matter, where everything seemed possible and, on occasions, collided. It took time and introspection to subdue this zest for the plasticity of the medium, eventually achieving the subtlety of delicate layers or glazes visible in his current work.

From expressionist human figures in the 1980s through to still lives in the 1990s, his work has evolved into austere canvases: fields of color in space where elliptical figures refer back to his earlier still lives. In other works, photos that he has taken of landscapes are projected onto the canvas, on which the landscape is then been painted in lighter and darker hues of the same color, both stressing and denying a monochromatic identity. In such works, the landscape is acknowledged, and yet is submitted to a mystical interpretation beyond shapes and perspective.

In 2005, experimenting with ink on paper, Cambre mixed several shades of green in different renderings on each sheet; the resulting wall installation of forty-five prints consisting of various shades of green, was first shown at the Wussman Gallery in San Telmo, Buenos Aires. These pieces were not intended to complement each other, but rather to accentuate the differences between them. In an exhibition entitled “Terminus” in 2015 in the Vasari Gallery, Buenos Aires, Cambre showed a wide range of disparate work: some paintings were opaque, others were illuminated with specks of light. One piece that especially stood out—a large work made up of twenty white paper squares divided by a thin wooden frame on which much smaller squares and rectangles painted in oil had been arbitrarily placed—is a visual testimony to the love of music and poetry that informs the creative work of this painter.

In Un Bárbaro en las Sierras (A Barbarian in the Hills) (2015) Cambre experimented on an unstretched canvas with a series of squares and rectangles in several colors framed by bright yellow lines; he translated the arrangement into blue on another square canvas, then copied the same shapes, but in different positions and in green, for an outdoor mural in Buenos Aires, before finally rearranging them again for a brown canvas in yet another configuration. The works that form this project are thus part of an extended conversation—a moderato cantabile, to use a musical analogy—between shape, space, and color.

– Alina Tortosa

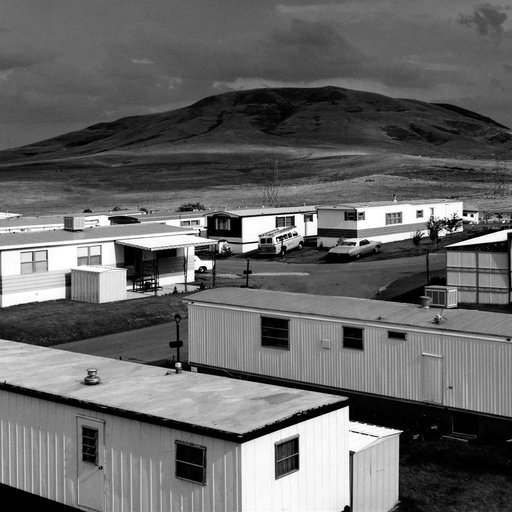

MARINA RHEINGANTZ

Born 1983, Araraquara, Brazil.

When asked about the subject matter of her luscious, fluid paintings, the American Color Field painter Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011) once remarked, “If I am forced to associate, I think of my pictures as explosive landscapes, worlds, and distances held on a flat surface.” Her words, spoken in 1957, resonate with the richly-hued landscapes by the Brazilian artist Marina Rheingantz. Like Frankenthaler, she evokes the genre of landscape painting in the loosest sense of the term, as her paintings hover on the periphery of abstraction.

Works such as Treino (Training) (2014) appear to materialize on the canvas via a process of introspection, which sees the artist amalgamating the exterior landscape of the arid, dusty desert lands of North-eastern Brazil, with visual fragments and remembered motifs that she has collected from photographs and found imagery. A gauzy, soft light emanates from the painting’s surface, which undulates in rosy patches that blush to warmer oranges and pinks, receding to cooler tones as our eyes lift towards the top of the canvas. Accents of small cobalt blue triangles and dots intermingle with the outlines of lightly traced hurdles; it is these that ground the picture in the history of landscape painting, as they interrupt the fluid swathes of pastel brushstrokes to demarcate spatial distance and establish a foreground that would otherwise be intangible.

What distinguishes many of Rheingantz’s landscapes is the artist’s tendency to banish horizons, so that we experience the paintings—which are often stretched across wide expanses of canvas—from a dream-like, warped perspective; their large scale impacting on the pace at which our eyes can take in the bigger picture, versus the details that we seek out upon closer inspection. Revoada (Flight) (2015) is such a painting. It has the feeling of an over-exposed photograph, in the mass of milky white paint that dominates much of the canvas, which gives the impression of a sun-bleached meeting of sky and sea, or perhaps the arid desert of the Caatinga region in Brazil, which has featured in a series of the artist’s paintings (the region’s name is derived from the Tupi word meaning “white vegetation”).

It is in works such as Veludo (Velvet) (2014) or Cruzeiro do Sul (Crux) (2015) that Rheingantz moves further into abstraction, overlaying loosely geometric motifs on top of deeply saturated oils. In the uniformity and repetition of the shapes, they seem to underline the formality of fixing nature into a stillness, but what unites these works with her more naturalistic landscapes are the deft, confident strokes of paint that seem to arrive effortlessly on the canvas, and their contradiction with the more preciously applied marks that flicker and activate the painting’s surface, along with our eye.

– Josephine New

[related-works-module]