Traditionally, history painting refers to large scale canvases that depicted an important event or action involving several people. Drawing from the legends of history, mythology, the Bible, imperial conquest, or folklore, the genre was considered to be one of the highest forms of painting before falling out of vogue in the 20th century in favor of the avant-garde developments we known and love. Still, the genre remains lastingly influential, and now some daring 21st century painters are updating the format, trading heroic Western stories for contemporary scenes reflecting their own globalized perspective. Here, we’ve chosen three international painters from Phaidon’sVitamin P3who each engage with art history to revitalize this forgotten genre and enter it into a critical, decolonizing discourse.

MICHAEL ARMITAGE

Born 1984, Nairobi, Kenya. Lives and works in London.

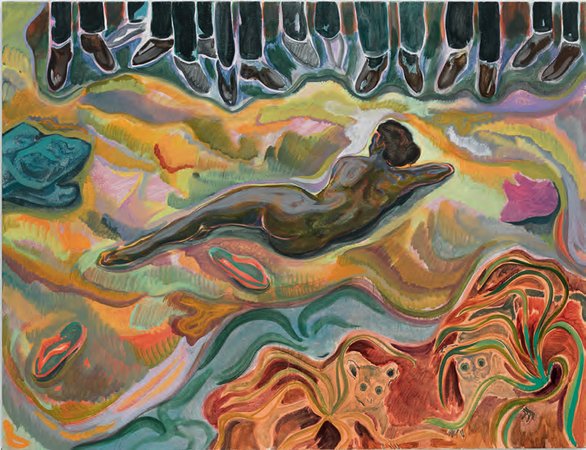

Michael Armitage shares his time between London and Nairobi. His large, colorful works are painted on lubugo, a traditional bark cloth from Uganda, whose surface provides a rough texture and occasional imperfections such as small holes. Often depicting scenes from traumatic events, Armitage’s canvases vibrate with the tension between a flamboyant color palette and serious subject matters. At the centre of #mydresschoice (2015) lies a naked female figure seen from behind and quoted directly from Diego Velázquez’s The Rokeby Venus (1647–51). Strewn around her are discarded items of clothing, a rumpled miniskirt and skimpy top. Facing her is a colonnade of male legs, standing as jury before her prone, unclothed body. The dazzling sun-drenched colors and steeply angled point of view combine with a vignette featuring a pair of bush babies in the lower right-hand corner, their wide eyes staring out in shock, to produce a scene tinged with phantasmagoria. Armitage describes the incident depicted, which took place in Nairobi in 2014, and the feelings that inspired the work: “women wearing miniskirts were taken off minibuses, stripped, and molested by the drivers, touts, and some passengers; this was filmed and circulated on the Internet. After watching, I felt complicit in the abuse … In the painting the most important character is you as the viewer.”

Armitage’s works operate as a type of contemporary history painting, and there is a radical edge to his depiction of events. He privileges minor, rather than official, histories in order to reveal everyday social and political realities. Deploying painting as a means to address the complexities, lacunae, and bitter ironies of history, Armitage combines artistic traditions from his dual heritage: the African ground of lubugo and the visual iconography of East Africa come together with imagery quoted from European art history. Accident (2015) shows the scene of a bus crash amid dense foliage in an array of greens, rendered in layer upon layer of oil paint. There is a liquid aspect to some of Armitage’s color washes, while other areas are scraped back to produce the effect of an afterimage, or to resemble pastel. Masses of green foliage underscored in contrasting reds and oranges churn like the roughest of seas; distorted bus seats and palm trees seem alive with a Cubist or Vorticist dynamism, conveying the confusion of catastrophe and the frustrating, fragmented quality of traumatic memory. The painting also holds an autobiographical significance for Armitage, recalling his experience of being in a plane crash in the Kenyan bush when he was a young man.

Armitage believes in the role of art as social commentary and he is confident of its capacity to generate debate and possibly even to produce change. While the sensual style and attractive colors of his paintings seduce us into the naive pleasure of looking, their titles offer clues to the distressing realities they so beautifully depict, sharpening our relationship with the scenes we observe.

– Ellen Mara De Wachter

DANIEL BOYD

Born 1982, Cairns, Queensland, Australia. Lives and works in Sydney.

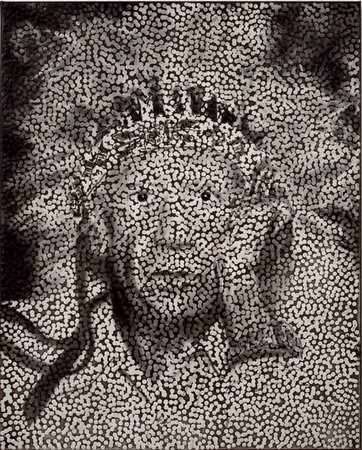

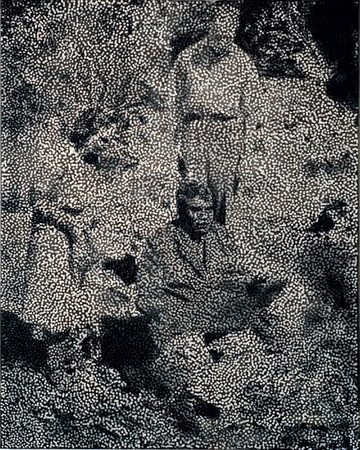

The paintings of Daniel Boyd, an Aboriginal Australian artist of the Kudjlat and Gangalu peoples with Vanuatuan heritage, question what it means to be a history painter today. Painting from nineteenth and twentieth-century photographs, Boyd reframes the visual narratives of indigenous people in the Pacific, including those of his ancestors. Using a technique that borrows from Central Australian Aboriginal dot painting and Impressionist pointillism—as much as it does from the lexicons of printing and photography—Boyd implicates Australia’s aesthetic history in its post-colonialist past and present.

Using the abstract technique of dot painting as a means to a figurative end, Boyd paints portraits and landscapes in oils, watercolor, or charcoal, before overlaying the painted surface with dots of archival glue. As if to emphasize that each painting is a record of loss, the image that remains outside of the glue is then painted—or “Black-ed”—out, so that only the raised dots remain. For Boyd, the historical record is best re-told through the gaps left by its missing parts. His monochrome paintings carry with them a nocturnal pall and, despite varying in scale, recall the epic night sky and the pixelated infinitude of digital screens. Atypical works in color, such as Untitled (PI3) (2013), an idyllic tropical scene, still carry a sense of being in black and white, or “touched up,” as if shaded by history. His series “Up in Smoke Tour” (2011) featured framed watercolors “Black-ed” out in Boyd’s signature style, hung alongside disused boxes that previously contained skulls from London’s Natural History Museum, and interned in a display cabinet.

If Primitivism (a neo-colonialist strategy wherein Western artists appropriated techniques, motifs and iconography from non-Western artists) was the Western colonization of the canvas, then Boyd’s paintings are almost reparative; emphasizing aesthetic beauty, while also chronicling oppression. To this end, his paintings detail encounters between Indigenous and Western artists, between modernism and its antecedents, quoting from the art historical canon. In Untitled (PIB) (2013), Picasso appears dressed up as a Native American in a headdress given to him by the actor Gary Cooper. In Untitled (NDD) (2013), Aboriginal artist Albert Namatjira (1902–1959) is pictured painting en plain air at Standley Chasm, with the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester peering over his shoulder.

Through his multifaceted painted surfaces, Boyd implicates art as being complicit in the artful remembrance of history. At the heart of his paintings are two conflicting experiences of time—one, the Western linearity of past, present and future; the other, the Aboriginal concept of the self as enmeshed with the land, best expressed in Australian Indigenous cosmology as “Dreaming.” Importantly, Boyd’s work positions this chronological opposition as being fundamental to Aboriginal and white relations in postcolonial Australia. In this way, Boyd’s paintings articulate the impossibility of representation, interpreting painting and history as similar approximations of the real.

– Stella Rosa McDonald

K.P. REJI

Born 1972, Kerala, India. Lives and works in Baroda, India.

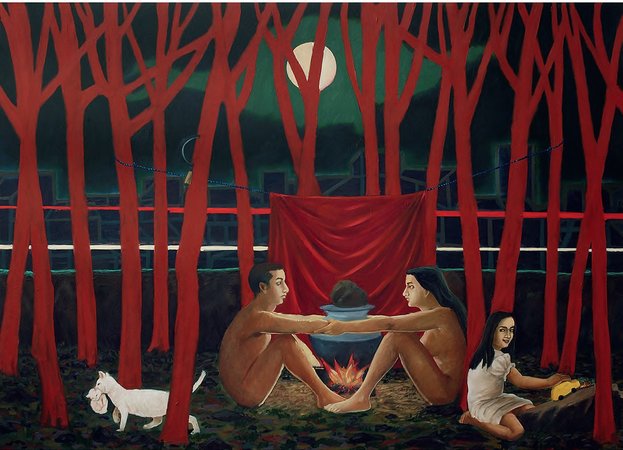

“It’s a delight to find paintings in the common and everyday,” says Indian artist K.P. Reji. Yet, in his paintings, the “common” always contains a whiff of the extraordinary; the “everyday” is invariably seasoned with something more sinister. In Dinner (With a Pinch of Salt) (2009) a couple sit down to a meal. Despite the straightforward title, the fare is highly spiced with mystery: the couple hold hands over a cauldron, naked in a forest setting. Trees with ruby-red trunks snake across the greeny-black backdrop. The viewer seems to have stumbled on a feast that is more magical than mundane.

Nothing is as it at first appears in Reji’s painted world. Like the late Bhupen Khakhar (1934–2003)—the lynchpin of Vadodara’s “narrative figurative” tradition in the 1980s—Reji’s images recall the “Company School Paintings” associated with the British Raj. These nineteenth-century artworks affected a merger between Moghul miniatures—with their two-dimensional, “flat” figuration and jewel-like colors—and the chiaroscuro of Neo-classical panoramas. Similarly, in To Move the Mountain (2007) the turquoise sky and a studiedly naive division of space bestow a contrived, theatrical air to proceedings. Here, a cardboard-colored truck is packed with tumbling toys, kitchen utensils and a tiny tree. We are reminded of a stage set, the various objects looking like props for a school play. A bald man has his back to us: is this Mahatma Gandhi, the Father of the Nation, preparing for a political performance?

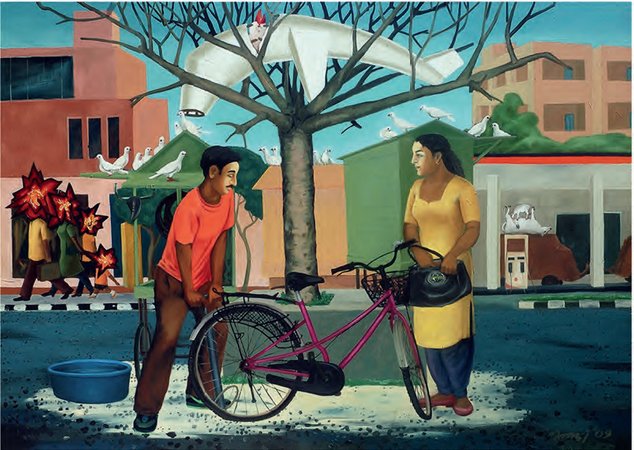

Reji also follows in the footsteps of other Malayali artists who studied at Vadodara’s Maharaja Sayajirao University: Jyothi Basu (b.1960), Shibu Natesan (b.1966) and Rajan Krishnan (b.1967) are known for their vividly colored, figurative canvases, conjuring mildly bizarre scenarios. Unlike them, though, Reji portrays the interaction between India’s working class and systemic violence. In The Birds (2009) a man and woman confer over a bicycle. A crowd of white birds congregates over their heads like mini-versions of the white airplane that has crashed into a nearby tree. The faces of a passing family are obscured by orangey-red flames: has the plane dropped bombs before crashing? Meanwhile, a tiny cow, with her suckling calf, lies upside down on the roof of a car. Since the cow is a sacred beast in Hinduism, this upended Maa seems to symbolize a society turned upside down.

Reji’s art probes the disintegration of traditional family and community relationships in the “new” India, following the globalization of the 1990s. “His works pay tribute to the working class in the universal sense of labour,” writes art historian Santhosh S. Significantly, Reji’s home state—Kerala—was the first state in the world to elect a Communist government in 1957. Are the comic book-like explosions in Girl with a Rooster (2010)—where a couple on a bicycle appear to burst into flames in the background just as an airplane flies across a stormy sky—meant to remind us of the five-pointed red star of Communism?

– Zehra Jumabhoy