Mona Hatoum has returned to the scene of her solo museum debut with a large-scale retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, which helped to launch her career back in 1994 when she was transitioning from performance and video art to sculpture and installation. The current exhibition (on view in Paris through September 28, and touring next year to the Tate Modern and the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki) features more than 100 works by the Palestinian-British artist, including many of her now-signature installations—subtly political, Minimalism-inflected combinations of light, metal, and glass that hint at issues such as identity and imperialism.

In this excerpt from Phaidon’s Defining Contemporary Art, the curator Connie Butler recalls her experience with Hatoum’s seminal 1989 work The Light At The End. More information on Hatoum’s work and career can be found in the Phaidon monograph Mona Hatoum, part of the Contemporary Artist Series.

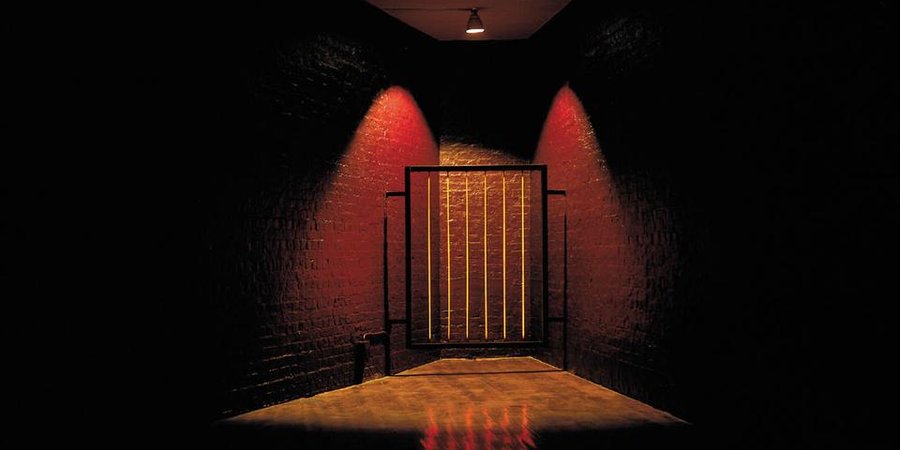

What I vividly recall about The Light at the End, which I saw in a show at New York’s Grey Art Gallery in 1991, is a visceral, physical response so strong it is still lodged in my kinaesthetic memory. The group exhibition was titled “Interrogating Identity” and it was striking to see so abstract a work in an exhibition laden with the discourse of identity politics that characterized that time. Moving from the lighted, street-facing galleries into the dark, claustrophobic environment of Mona Hatoum’s installation was a shock to the system. As one’s eyes adjusted to the thick darkness, at the back of a long, narrow space a vertical row of six heating rods became gradually visible, illuminated by a single spotlight. What from afar resembled a cool minimalist form – six perfect red lines in space – quickly became more menacing as one became aware of the searing heat emanating from it. Moving closer, one’s own body became the performative vehicle for the production of meaning. Measuring the distance between the rods as roughly approximate to the width of a head, one was forced to physically acknowledge one’s own space and bodily dimensions in relationship to the work. Taunting the desire for a happy end, the grid functioned as a prison or a device of torture and immanent harm.

Looking at the titles of group exhibitions in which Hatoum was included at the time (“The Interrupted Life,” “Shocks to the System: Social and Political Issues in Recent British Art,” “The Other Story: Asian, African and Caribbean Artists in Post-War Britain”) indicates how her works’ rigorous geometry and the reductive seriality of her cold, often charged materials yielded a social or political reading. In Light Sentence (1992) – another major piece from this body of work using light, a grid and the presence of real or implied danger – a structure made of stacked cages illuminated by a bare bulb is made ethereal as the bulb moves slowly up and down and the vertiginous shadows grow and shrink. As in The Light at the End, the effect on the viewer was unsettling, even nauseating, and unforgettable. The conflicting realities of vision and obfuscation, immutable physical experience and an enervating sense of tension and bodily harm are calibrated with a precision that anticipates such later works as Alfredo Jaar’s Lament of the Images (2002) or the grotesque and affecting institutional interventions of Mexican artist Teresa Margolles.

The Light at the End is generally considered the starting point of a new phase in Hatoum’s practice, though it is clearly grounded in her earlier thinking. As an art student in London in the late 1970s, she experimented with performance art and video, and later continued to create works in these mediums to challenge common taboos that isolate the reality of the human body. In Waterworks (1981), footage from cameras in the men’s and women’s lavatories were intended for display on a monitor in a public gallery’s hallway, revealing a very familiar activity that is always hidden. In other performances from the 1980s, Hatoum employed her own body, dragging herself through a park in Bracknell, Berkshire, in Them and Us … and Other Divisions (1984), and sequestering herself in the shantylike space she created for Matters of Gravity (1987), visible to the viewer only through a small hole as she struggled to interact with everyday objects – a bed, a chair – stuck to the wall.

This idea of barriers – between people in different circumstances, between people’s physical realities and their acceptance of them, a sense of the uncanny and the apprehension of danger in the formerly innocuous – is critical to The Light at the End and is increasingly operative in her more recent work. Hatoum has said, “The Light at the End was the beginning of a whole new way of working. In a sense with this work I was going back to a minimal aesthetic and working with certain material properties which amplify the concept. The associations with imprisonment, torture and pain were suggested by the physical aspect of the work and the phenomenology of the materials used. It was not so much a representation of something else but the real thing in itself. I felt satisfied for the first time that the balance between the issues, the materials and the space was just right for me. It also had this paradoxical aspect of being both attractive and repulsive. It was obscene. The space at the back of the Showroom [the London gallery where it was first shown] is this strange funnel shape, which made me think of a trompe l’oeil perspective of a tunnel. The expression ‘the light at the end of the tunnel’ came to mind, and I used it in the title to set up the expectation of something positive which is then disrupted when you realize that the light was actually red hot bars that could burn you to the bone.”