It’s back-to-school time, and in honor of the season we’re taking a look back at Mike Kelley’s seminal work Educational Complex from 1995. Made famous by his visceral, psychologically-driven videos and assemblages of stuffed animals, Kelley has come to be considered one of the most important American artists of recent years, especially in his adopted city of Los Angeles. In this essay, originally published in Phaidon’s Defining Contemporary Art, Hammer Museum chief curator Connie Butler shows how the artist’s experiences in his original home town—Detroit—continued to influence his work years long after he left the city. Here, repressed memories and a kind of sick nostalgia activate scale models of his childhood house and various schools, reconstructed according to Kelley’s idiosyncratic approach. For more models by the late artist, be sure to check out the new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth (opening September 10), featuring Kelley’s interpretations of Superman’s home city of Kandor.

Though he has been based in Los Angeles since 1976, Mike Kelley’s birthplace of Detroit has always been a locus of his practice, as has his working method of creating psychologically charged architecture—as scale models and as life size environments—for chaotic, often scatological accumulations of personal memories and cultural detritus. Examples include works in which an imagined territory gives structure to a larger narrative, as with the landscape photographs in Three Valleys (1980) or the drawings in Monkey Island (1982-83); sculptural landscapes composed of found children’s blankets and pathetic pre-owned dolls or pet toys, such as Mooner or Arena 5 (both 1990); and the sock monkeys and related stuffed animals grouped and organized on generic industrial work tables in Craft Morphology Flow Chart (1991).

Kelley’s integration of personal, architectural, and cultural memory reached its apotheosis in 1995 with Educational Complex. In American culture of the 1980s and 1990s, the suburban school became a territory heavily charged with symbolism in the wake of several high-profile school shootings and child-abuse cases. Locations such as Columbine, Colorado, and Manhattan Beach, California—home of the McMartin preschool, another subject of Kelley’s—are indelibly etched in the American psyche as painful examples of aggression or “repressed memory syndrome” incubated in neighborhoods that had once held promise for upwardly mobile families fleeing the inner city. In Kelley’s work, this dark and paranoid side of American culture is exploited and filtered through the artist’s own memories of his childhood experiences in Detroit, one of the most economically blighted cities in the United States. Like other American artists, such as Paul McCarthy, who mines the territory of his own Mormon upbringing, or Matthew Barney, who has used the American West as the cinematic backdrop for his epic films, Kelley is interested in icons of the benign relics of his own psyche—in his case, the wishing well, the office, the museum, the classroom.

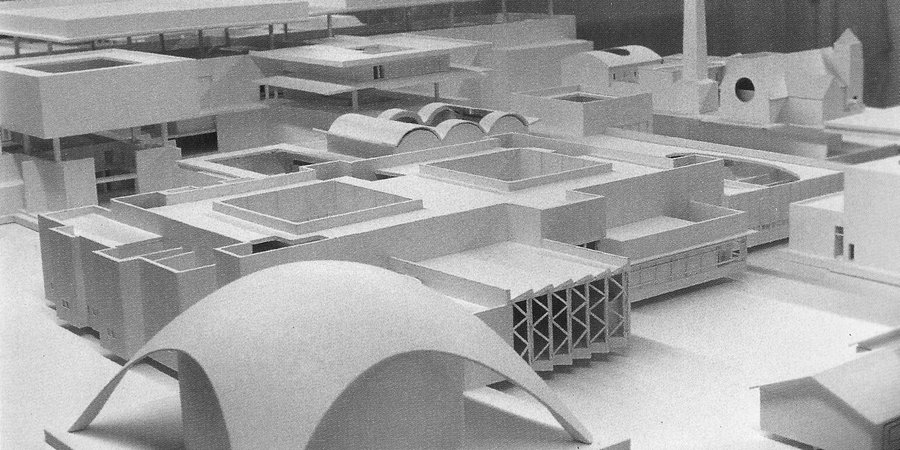

In 1995, addressing what he calls his “bias against architecture” Kelley created Educational Complex, a tabletop model that delineates the psychogeography of his childhood by reconstructing from memory the schools he attended and the house in which he grew up. “Buildings that I had occupied almost every day for years could barely be recalled. The teachers, courses and activities held within them are a vast undifferentiated swamp.” Generated through a process of drawing and modeling, the complex of structures was a combination of excavation and spatialization of memory. Classrooms, hallways and offices were recalled, drawn, and then matched to actual floorplans. The resulting form became a conflation of the two.

The gaps in memory—the lapses and repressed moments—are represented by actual blanks in the architecture of the model, spaces filled in. Doors recalled as opening on the left are represented as doing so on the right, while other mistakes are left uncorrected, representing what Anthony Vidler has called “a nostalgia for the homely.” As Kelley has said, “In utopian projects, moral and aesthetic dimensions are presented, often openly and dramatically, as mirrors of each other. Of course, my project is a perversion of such an attitude: I present an obviously dystopian architecture, reflecting our true, chaotic social conditions, rather than some idealized dream of wholeness.”