Christie's auction house is best best known for its high-profile art auctions, whose sales routinely number in the millions. Artworks, however, are far from the only valuebles that cross the auction block. Up for grabs next month, for instance, is a 7mm six-shooter, referred to as the “most famous gun in French literature” for its use by the Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine in an attempt to kill his teenage poet lover, Arthur Rimbaud. It is expected to sell for $55,000 to $76,000.

Christie’s long and colorful history is chronicled in Phaidon'sGoing Once, a collection of the most significant, and strangest, lots ever auctioned over the course of the auction house's 250 years of business. In honor of Verlaine’s gun hitting the auction block, we’ve selected some of our favorite oddities from the legendary auction house’s past.

1. GOLDEN FINGERS AT GOLDENEYE

“My love,” wrote Ian Fleming (1908–1964) to his new wife, Ann, in August 1952, “this is only a tiny letter to try out my new typewriter and to see if it will write golden words since it is made of gold.”

The gold-plated Royal Quiet De Luxe, made by the Royal Typewriter Company of New York, was a gift that Fleming had bought for himself as a reward for finishing a draft of the first James Bond novel, Casino Royale (1953). The next draft of that book, and all the subsequent Bond stories including Goldfinger (1959), and The Man with the Golden Gun (1965), were written on the same golden typewriter at Fleming’s Jamaican retreat, Goldeneye. Clearly, Fleming had a fondness for gold’s glister and all that it signified.

The golden typewriter cost Fleming $174 (equivalent to about $2,000). He asked a friend, Ivar Bryce, to pick it up for him in New York and bring it back to England, adding mysteriously: “I will not tell you why I am acquiring this machine.” Presumably, the existence of James Bond was still something Fleming wanted to keep under wraps at this stage. By the time the typewriter came up for auction forty years later, 007 had become a global phenomenon. The suave spy’s every utterance and action had come to life on this very machine, which made it one of the most exciting pieces of literary memorabilia ever to be offered by Christie’s. The golden typewriter sold for £55,750, more than ten times its low estimate, making it officially the most valuable typewriter in the world. The identity of the buyer remained, appropriately enough, a secret.

2. DEADLY BIRDSONG

Attributed to Frères Rochat, pair of mirror-image singing bird pistols, c.1820. Sold May 30th, 2011 for $5,843,100.

Attributed to Frères Rochat, pair of mirror-image singing bird pistols, c.1820. Sold May 30th, 2011 for $5,843,100.

Why should a pair of pistols—no matter how exquisite—appear in a sale of watches? The reason lies in the complex clockwork mechanism that allows birds hidden within the pistols to sing.

These ornamental weapons were made for imperial Chinese patrons during a period when automata (moving objects) were constructed especially for the Ottoman Empire and Indian royalty, as well as European aristocrats and royal families. Swiss craftsmanship and technology were highly prized, particularly that of the three Rochat brothers of Geneva, who specialized in singing birds that appeared in boxes or pistols, of which these examples were the most advanced.

Thanks to a mechanism made up of several hundred screws and wheels, the tiny multicolored feathered birds flip up from inside the barrels when the triggers are pressed. The barrel covers open to reveal bouquets of flowers over turquoise enamel. The exquisite creatures turn, flap their wings and move their beaks and tails in time to lifelike birdsong, automatically retreating into the barrels once the music has finished. Elsewhere, the detailing is just as sumptuous. The pistols are made of gold with scarlet enamel grips inset with pearls and diamonds, and two plaques on each depict a stag and a lion. These pistols remain in exceptional condition, with the mechanism in perfect working order.

Such artifacts were made in extremely limited numbers, and only four other examples are known to exist, none of them in pairs. The 2011 sale prompted an epic bidding war between connoisseurs that lasted for ten minutes before finally settling with one proud buyer.

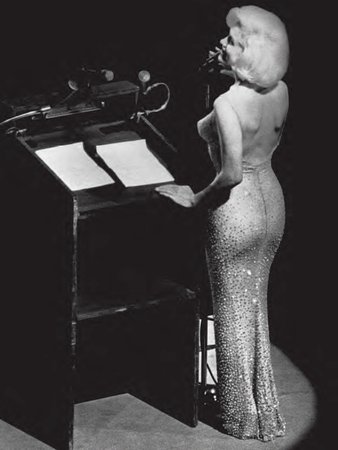

3. HAPPY BIRTHDAY MR. PRESIDENT

Undoubtedly the most famous rendition of “Happy Birthday” ever performed was that by Marilyn Monroe on May 19th, 1962 at a birthday tribute for President (and alleged lover) John F. Kennedy. It is now seen as especially poignant because it was one of the film star’s last public appearances before her tragic death, less than three months later.

Held at New York’s Madison Square Garden, the Democratic Party’s fundraising gala of 1962 was attended by some 15,000 guests and filmed by the CBS television network. Monroe was keen to make an impact, and contacted the Hollywood costume designer Jean Louis, saying: “I want you to design a truly historical dress, a dazzling dress that’s one of a kind.” Louis created a stunning piece from layers of flesh-colored silk soufflé gauze, covered in rhinestones.

Louis decided to play on Monroe’s sense of daring. “Marilyn had a totally charming way of boldly displaying her body and remaining elegant,” he explained later. The delicate fabric was ordered from France and cut by Louis’s couture staff, many of whom had been trained in Paris. Some 200 tiny panels were stitched with 6,000 crystal beads to provide a semblance of modesty. To ensure that it fitted like a second skin, Monroe was zipped into the dress without underwear, and extra stitching was added on the night. The effort was worthwhile judging by the gasps that were audible when she took to the stage.

For four decades after Monroe’s death, the dress—along with the rest of her private possessions—was kept out of sight and untouched, cared for by the family of Monroe’s acting coach Lee Strasberg, to whom she had left her belongings, ranging from the contents of her library to a baby grand piano.

When this lot was auctioned, all the lights in the salesroom went out. Suddenly Marilyn's voice could be heard, singing “Happy Birthday.” The dress was then spotlit and bidding opened. The dress went on to set a world record for a woman’s costume, and set the third highest price ever paid for an item of celebrity memorabilia. When the gavel came down at over $1.2m the winning bidder—and Marilyn—were given a standing ovation.

4. THE RIGHT TO BE HEARD

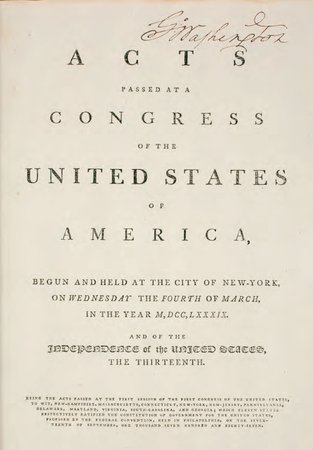

George Washington’s personal copy of the us Constitution and Bill of Rights, dating to 1789, came under the hammer in 2012, and set a new record for an American book or historic document at auction.

The first president’s gold-embossed, leather-bound volume runs to 106 pages, carries his personal signature and features his family coat of arms on the front endpaper alongside his motto, “exitus acta probat” (The end justifies the deed). It is a record of an extraordinary period in which the United States was born and its Constitution and much-debated Bill of Rights adopted. But it is also a vivid testimony to Washington’s own journey, from commander-in-chief of the continental army in the American Revolution to the country’s first president. Washington’s own handwritten marginal notes highlight key passages concerning the responsibilities of the president, emphasizing his desire to adhere to the Constitution. He once wrote: “The Constitution is our guide, which I will never abandon.”

The original Constitution, which had been written in Philadelphia in 1787, emphasized the machinery of effective federal government, rather than individual rights. The amendments that make up the Bill of Rights—establishing fundamental liberties such as the rights to free speech, press, assembly, and religion—were a concession that secured the Constitution’s hard-won ratification.

Washington was the only president to win unanimous approval by the electoral college, and he did it twice. On his retirement from the presidency in 1797 he brought the book home to Mount Vernon, his plantation estate 15 miles south of Washington, DC, where it stayed in the hands of the Washington family until 1876. It then passed into private ownership, and for a time was in the collection of the newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst. It was sold in 2012 by the estate of the businessman and philanthropist, Richard Dietrich, and purchased by the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, which maintains the Mount Vernon estate. A foundation document in American history and the treasured possession of one of the nation’s founding fathers, it has finally returned to its original home.

5. DEATH AND HONOR

The elite warrior caste of the samurai was a defining force in Japan from the twelfth to the late nineteenth century. Bound by the strict code of bushidō (“the way of the warrior”), they created a unique culture that encompassed everything from tea ceremonies to ink paintings and poetry. The samurai’s world view was defined by discipline, diligence, obedience, duty, and—perhaps most importantly—an unshakeable belief in the importance of dying well.

Bushidō required that a samurai’s death should bring only honor to those he served. He must fight to the end, even if this required seppuku – ritual suicide – in order to avoid the humiliation of defeat. Such a ritualized way of life and death engendered an ancillary culture of Japanese craftsmen and artisans who, over many generations, crafted and perfected the instruments of the samurai’s way of life, including the arms and armor befitting such warriors. As a result, the appurtenances of the samurai are regarded as examples of stunning design: objects that blend efficiency, beauty, and poise.

In 1990, Japan suffered an economic downturn that took the heat out of most of its once-booming markets, including the thriving international trade in traditional Japanese art and artifacts. By 2007, some auction houses had even begun to close their Japanese departments. In 2009, however, with Japan slowly emerging from its economic doldrums, a rise in Western interest in that country became evident in New York, with both Christie’s and the Metropolitan Museum of Art organizing events dedicated to the inimitable craftsmanship and visual splendor of samurai culture.

This red-and-blue-laced gold-lacquered armor formed the highlight of the sale in 2009. It hailed from the 300-year-old collection of the Kii Tokugawa family, a branch of the Tokugawa clan whose power as shoguns (military leaders) allowed them to dominate Japan during the Edo period. The piece is considered to be a masterpiece of seventeenth-century gusoku, the Japanese armor that came to define the look of the samurai. Estimated to fetch $250,000–300,000, it doubled this to sell for $602,500—proof that the Japanese art market was on the rise again.

6. THE STONE FROM OUTER SPACE

A complete stony meteorite from L'Aigle, Orne, France, 1803. One similar to this sold on April 8th, 1998 for $42,225.

A complete stony meteorite from L'Aigle, Orne, France, 1803. One similar to this sold on April 8th, 1998 for $42,225.

Those who gathered at Christie’s South Kensington on 8 April 1998 would have been forgiven for thinking there was something a little otherworldly about the proceedings, at least where Lot 8 was concerned. Most of the objects for sale were scientific instruments, but this lot was a little different: the first meteorite ever to be sold by the auction house.

This small fragment from outer space spoke not just of the romance of other worlds, but also of a time when the mysteries of the galaxy were even less well understood than they are today. The meteorite had fallen to Earth in France on 26 April 1803, and its arrival rocked a scientific world that was still debating whether in fact it was possible for objects to fall from outer space.

The astronomer Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774–1862) visited the site, where he learned that a fireball had been seen in the sky, followed by a shower of stones weighing a total of about 82 lb. He collected specimens, many of which are now in the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and recorded eyewitness accounts. “The freshly fallen stones taken into houses gave out such a disagreeable smell of sulphur that they had to be taken outside,” Biot noted. After he wrote a report on the incident and presented his evidence to the French Academy of Sciences in 1806, it was acknowledged, finally, that meteorites existed.

Lot 8 sold for £25,300, more than double its high estimate, and ever since that first sale Christie’s has catered to a growing number of collectors. In 2014, the first dedicated meteorite sale was held in the United States: the most valuable lot, a Martian meteorite called “Black Beauty,” sold for $81,250.

7. REMAINS OF THE DAY

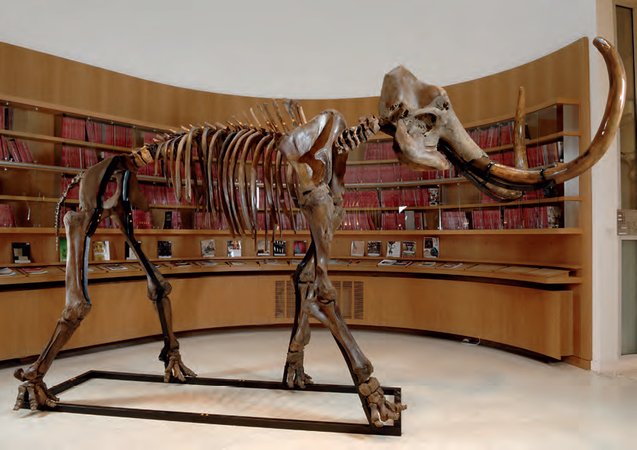

The mammoth’s skull looks like an octopus sculpted in mahogany, its enormous tusks curving upwards, while the thick femurs have the beautiful deep-brown patina of a Chippendale sideboard. This enormous creature, whose complete skeleton was sold in 2007, lived and died in Siberia during the Quaternary period, about 15,000 years ago.

Before the sale, the mammoth had been nicknamed “The President” in honor of another Siberian, Boris Yeltsin, the ailing former president of Russia (he died a few days after the sale). It was by no means the oldest thing up for auction that day—there were four-million-year-old trilobite fossils—but the mammoth was the spectacular centerpiece of the sale. A spokesman for Christie’s described the mammoth as ‘exceptionally large’, but that understatement was not quite to the point. The key thing about this skeleton was that it was complete, a more or less perfect specimen of Mammuthus primigenius. Its wholeness, as much as its immensity, was what made it compelling for collectors of paleontological curiosities.

The skeleton set a new world record for this kind of object. Not everyone was pleased to see the mammoth pass into private hands rather than go to a scientific institution. “It is a pernicious consequence of the Jurassic Park effect,” complained Pascal Tassy, a professor at the Natural History Museum in Paris. Most people merely wondered how the new owner of The President would make room in their house for it.

[related-works-module]