In the ancient world, long before the widespread adoption of monotheistic, patriarchal forms of religious worship, goddesses served vital roles in their respective pantheons. Representing everything from nature and fertility to power, revenge, and beauty, these statues of female deities (each excerpted from Phaidon's30,000 Years of Art) are some of the finest examples of ancient art still in existence.

VENUS OF WILLENDORF

Artist Unknown

Gravettian Period, Austria

c. 25000 BC

This rare example of a venus carved confidently from hard limestone is an icon of Palaeolithic art. It is one of three ‘venus’ figurines found on archaeological sites at Willendorf, in lower Austria near Krems. These sites have yielded rich evidence of temporary camps of the Gravettian period (c.28,000–19,000 BC). The figurine depicts a short, rounded female originally colored red. As with other Gravettian venuses the breasts and thighs are extremely exaggerated, and the legs taper downwards, ending a little below the knees. Venuses often lack lower arms and hands, but in this case the hands are shown resting above the breasts. The face is blank, but the head is engraved with wavy lines in a spiral design that probably depicts a hat of woven fibers. The navel and the pubic opening are well defined.

A ritual function for venus figurines is suggested, although the specific nature of this is unknown. Suggestions include a role as mother goddesses, or symbolic icons of fertility or gender symbolism. The lack of attention to the face may indicate that the figurines are looking down, and it has been suggested that they are in an attitude of submission.

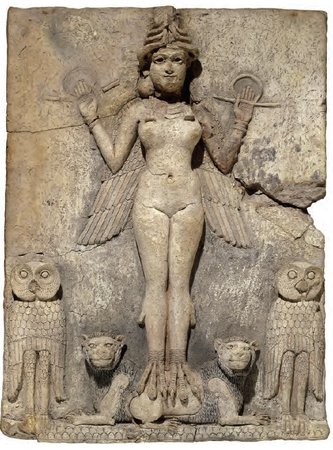

QUEEN OF THE NIGHT

Artist unknown

Old Babylonian Period, Iraq

c. 1775 BC

Also known as the Burney Relief after a former owner, the Queen of the Night is one of the most striking and enigmatic pieces of Old Babylonian (c.1900–1600 BC) art. Although it is immediately clear that the woman represented on the baked terracotta votive plaque is a goddess – both her horned cap and the rod and ring thought to symbolize judgment and/or justice are reserved for deities – her exact identity remains uncertain. The downward-pointing wings associate her with the Underworld, while the owls and surviving traces of black paint on the background suggest an association with the night. The same figure occurs repeatedly on votive plaques of the period.

Although some have seen the demoness Lilitu (biblical Lilith) in the sculpture, the strongest possibilities for the figure’s identity are Ishtar (Sumerian Inanna) and her sister Ereshkigal. Ishtar was the goddess of love and of war and was associated with lions such as those beneath the feet – or rather talons – of the Queen of the Night. Ereshkigal was queen of the Underworld and ruled with her consort Nergal, a god of war and disease. In either case it is possible that the relief relates to an aspect of Ishtar’s descent to the Underworld, a myth in which the goddess ventures into the realm of the dead to challenge her sister. On this journey, Ishtar’s jewelry and clothing are ritually stripped away before she confronts Ereshkigal.

SNAKE GODDESS

Artist unknown

Minoan Neo-palatial Period, Greece

c. 1500 BC

This figurine, dating to the Neopalatial period (c.1600–1425 BC), is one of three faience female statuettes found in the Temple Repositories at the Minoan palace of Knossos – two stone-lined cists (box-shaped chambers) located near the Throne Room that contained pottery, clay seal impressions and faience objects. She wears the typical Minoan female costume, consisting of a tight, breast revealing bodice and flounced skirt, and holds two writhing snakes in her outstretched arms; she is one of two “assistants” to a larger figure.

The significance of the Snake Goddesses is uncertain, but their location near the Throne Room suggests that they may have been used in a ritual performance associated with cult practices at the palace. They may also have been linked to “mistress of the animals” representations, a Near Eastern-derived cult motif consisting of a female flanked by two animals. Faience is an artificial vitreous material with a silicate body (made from sand or crushed quartz) and glazed surface layer, colored with metal oxides. The technology was imported from Egypt or the Levant during the second millennium BC and used on Crete to produce a range of vessels, inlays, seals and figurines. The Snake Goddesses are the most elaborate faience objects known from Crete, featuring intricate modeling, polychrome patterning and complex assembly from multiple parts (torso, limbs, and snakes).

COSMETICS BOX LID

Artist Unknown

Hybridizing Style, Syria

c. 1250 BC

This thirteenth-century BC ivory carving, originally the lid of a box that probably held cosmetics or jewelry, shows interesting Aegean and specifically Mycenaean influence on a traditional Near Eastern subject and composition. A divinity – a goddess whose name differs across the eastern Mediterranean and Near East but who is commonly known as the “mistress of the animals” – is surrounded by symbols of natural life broadly relating to the fertility of the land. Here the goddess feeds ears of corn to two goats reared up on their hind legs in a manner traditional in Mesopotamian art.

Links to Mycenaean art are visible in the costume of the goddess, in the profile and expression of her face, and in the arrangement of her hair. Like many later ivories, this is a good example of artists from Syria and the Levant producing original hybrids based on the arts of many Mediterranean and Near Eastern societies. The elephant ivory of which the lid is made also hints at the world of long-distance trade and interaction. The lid comes from Minet el-Beida, the ancient port of Ugarit (Ras Shamra), in Syria.

LADY OF ELCHE

Artist Unknown

Greco-Iberian Tradition, Spain

c. 400 BC

This enigmatic sculpture was discovered in 1897 at Elche in Alicante, on the southeast coast of Spain. In addition to the Punic (western Phoenician) and Greek influences that have been seen in the stylistic treatment of the figure, the Lady of Elche presents interesting native elements in its ornament and costume; as such, it is considered a masterpiece of Greco-Iberian hybrid art. Iberian elements of the sculpture have been identified in the elaborate headdress and jewelry, which correspond with descriptions of Iberian women left by Artemedorus of Ephesus, a Greek writer who visited the Iberian peninsula around AD 100. Greek influences are seen in the hollow eyes, which would have been inlaid with colored glass, and in the realism and detail of the figure, which was executed in a severe style suggesting a possible early fifth-century BC date, though other suggestions range as late as the Hellenistic or Roman periods.

The intricate ornamentation and unusual headdress of the figure have been meticulously studied in an attempt to discover her identity, but many questions remain unanswered. She is assumed to represent an indigenous goddess of fertility and death. A hollow opening at the back is also found in other sculptures from this period, such as the Lady of Baza (also in the Museo Arqueolgico, Madrid) and reinforces the notion that the sculpture served a ritual function.

STATUEETTE OF A GODDESS

Artist Unknown

Etruscan Civilization, Italy

c. 350 BC

Excavations (1885–1895) of the Sanctuary of Diana at Lake Nemi, near Rome, uncovered a large deposit of votive offerings, including many statuettes in the attenuated style of which this is the finest example. The goddess wears a long, clinging dress (chiton) and calcei repandi – the shoes with upturned toes for which the Etruscans were famous. She has a flat, plank-like body, from which only knobbly knees and small conical breasts protrude. This contrasts with the finely incised details of shoelaces and a waving hairstyle, parted and pulled in loose waves into a chignon underneath the cross-hatched diadem. The figure looks straight ahead, eyes slightly downcast, and has a straight mouth and firm, squared chin. Engraved ridges for upper and lower eyelids exaggerate the size of her eyes, a characteristic Etruscan practice. Her arms, schematically indicated, are held tightly against her sides. Only the hemline indicates the bottom of her sheath-like dress.

The contrast of the regular facial features with the simplified body gives this well-made figure an arresting appearance. A votive tradition of northern Etruria did include thin, stick-like figures, sometimes offered in healing cults. An Etruscan divinatory calendar speaks of “the most healthful leanness for bodies” – perhaps what the artist intended to portray in this figure. It has often been assumed that these figures influenced the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti.

VENUS DI MILO

Alexandros of Antioch

Late Hellenistic Period, Greece

c. 100 BC

Discovered in 1820 on the Greek island of Melos, the Venus di Milo was long considered the work of a fifth-century BC student of the great Athenian sculptor Pheidias (c.490–430 BC) and thus the embodiment of the Classical canon of female beauty. Although the basic pose and the position of the drapery echo a widely copied Early Classical (c.480–450 BC) Aphrodite type, stylistic considerations now place the work between 150 and 50 BC. In this Hellenistic sculpture the artist gives the figure more dramatic drapery than earlier types and soft, sensuous flesh, adapting and innovating to create a timeless masterpiece. A now lost section of the base bore the signature of Alexandros of Antioch.

The goddess would have been admired by young Greek students and athletes in its setting in a niche at the civic gymnasium of Melos. The surviving armless icon, of Parian marble, is far from her original appearance, however. Created in sections joined with dowelling rods, the most convincing reconstruction shows the goddess with her right arm gesturing to her left hand, which rested on a plinth. In her left palm an apple would have signaled her victory in the Judgement of Paris and punned on her island location of Melos (“apple”). She wore metal jewelry and was probably originally painted for greater realism.

YAKSHI

Artist unknown

Mauryan Empire, Ashokan School, India

c. 100 BC

The Mauryan Empire reached its zenith under the Buddhist emperor Ashoka (304–232 BC), a convert who was responsible for a flowering of Buddhist art and architecture across India in the third century BC. Although Persian or Persian-trained Greek sculptors, who moved to the region after Alexander the Great’s incursions in the fourth century BC, introduced new stone-carving techniques and motifs, sculptural forms nevertheless remained characteristically Indian. This Yakshi, or female nature divinity, often called the Venus di Milo of India, is a masterpiece of freestanding Ashokan sculpture; made of Chunar sandstone, she holds a yak’s-tail flywhisk (cauri), a sign of honor. Such figures may have served to accustom Mauryan worshippers to the newly official faith, the sculptures either being worshipped independently or functioning as guards of honor at Buddhist shrines.

This piece, dated broadly to c.300 BC–AD 100 and found at Didargani in Bihar, possesses a powerful monumentality and voluptuous realism, with sensuous folds of flesh and an hourglass waist. The slight bend in the left leg endows the figure with a subtle impression of graceful motion, which some observers have described as the “gait of a swan,” while the fine gloss of the skin, referred to as “Mauryan polish,” contrasts starkly with the meticulously carved details of her adornments.