Whether you’ve just come from Pipilotti Rist’s cornucopia of eroticism, old school low-def video, and advertising-latent retrospective at the New Museum, or the indulgent spectacle of Dreamlands at the Whitney, video art can still be an opaque and confusing medium. Though it began when artists like Marina Abramovic started experimenting with film and video as documentation, it then evolved into videos that were artworks in their own right. In the 1970s equipment was expensive—but getting cheaper—and its high cost excluded many artists, adding to the nascent genre’s rarity and novel appeal. Now, the digital revolution means nearly everyone has a 4K camera in their pocket and screens have proliferated—we are constantly surrounded by video billboards, television, and edgy web content. Artists like Hito Steyerl have almost entirely video-based practices, Thomas Hirschorn records himself indifferently flipping through photographs of war and violence on his iPad, and the New Museum and the Whitney have launched (the aforementioned) expansive shows with video at their core. A once obscure and avant garde medium, video art is now as mainstream as it gets, and its popularity isn't exactly waning.

To help understand this ever-expanding form, below we’ve excerpted an entry from Phaidon’s Art in Time on the history and implications of video art.

The invention in the mid-twentieth century of television and video offered artists a new medium in the making of art. Many artists first used video simply to record their performance art, but others began experimenting with effects and images that could be produced only through this medium. Video art began to include viewings in museums and galleries, the inclusion of video elements in sculptural installations, and live broadcasts. The rise of video in the fine arts paralleled its use in the entertainment industry and mass media, though video artists have often been critical of commercial video’s aesthetic and content.

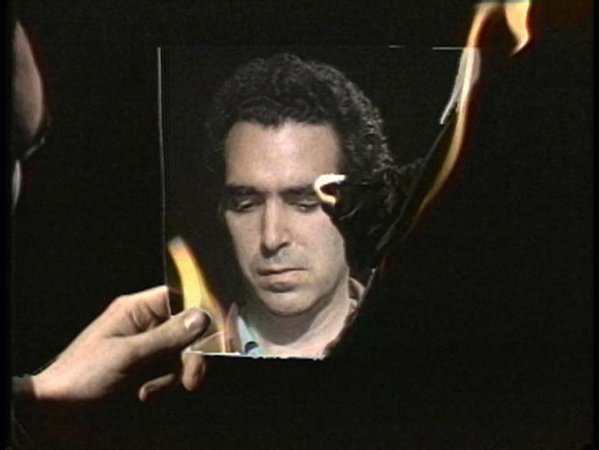

In the 1970s, video recorders, previously available only to commercial broadcasting companies and film studios, became affordable for consumers. Artists such as Peter Campus (b. 1937) explored effects that could be uniquely generated through video, just as abstract painters did earlier in the century with their medium. In Three Transitions, Campus employed green-screen effects and superimpositions to surreal ends: tearing through his torso as if it were a piece of paper, wiping his visage away uncannily to reveal a new image of his face, setting flame to a photograph of his moving yet indifferent visage.

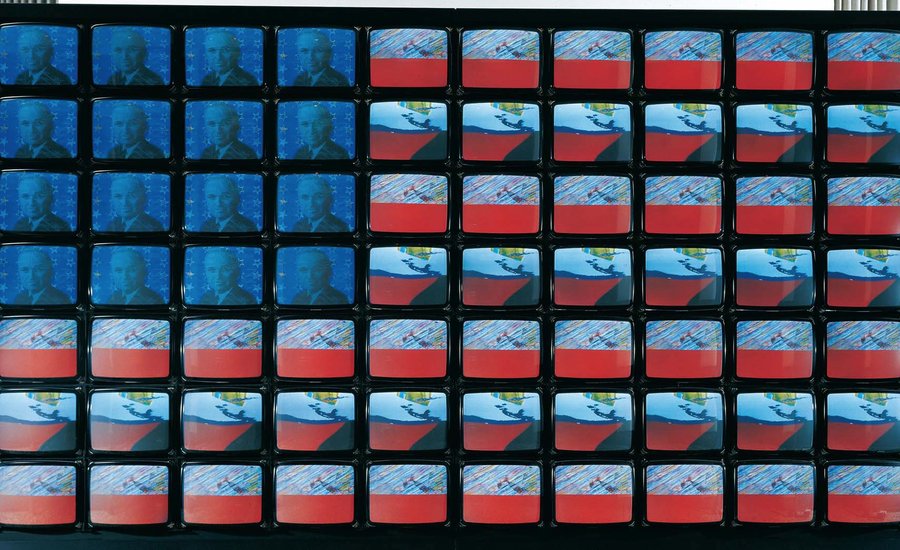

With the 1980s came the establishment of Video art as a recognized artistic genre with its own body of criticism. An iconic work from this period is Video Flag, the wall of television monitors by Nam June Paik (1932–2006). Video Flag overwhelms the viewer with an ever-changing stream of flickering images that periodically synchronize to form a giant image of the American flag or its negative. The incessant flashing of appropriated images of post-1945 presidents, random news footage, and digital ones and zeros mirrors the bombardment of contemporary society by mass-media images. The hyperactivity on the screens makes it difficult to focus on any single image. Thus the work bears witness to the new visual regime that accompanies contemporary society, one of spectacle and distraction and one that is distinctly at odds with the slow, contemplative looking traditionally associated with art. Paik, a former Fluxus member, had been a pioneer of video art, beginning with his experiments in 1959 in which he manipulated television images with powerful magnets affixed to the monitors.

Tony Oursler (b. 1957) merges video and sculpture, projecting videos of human faces onto three-dimensional orbs and doll-like bodies, usually accompanied by an audio track of the human voice. The often grotesque results blur the line between human and object, reality and artifice. In Blue Husk, he projected the video of a human face onto a transparent, three-dimensional fiberglass form. The video can be read on the surface of the form and on the wall behind it, though the latter image is distorted by the irregular shapes of the transparent object. Oursler does not confine his image to a television screen; like many video artists from the 1990s to the present, he uses projected images in a gallery space to create new and compelling encounters between the medium and the viewer.