What role does art play in your life? In Phaidon'sArt as Therapy—recently re-relased in paperback—authors Alain de Botton and John Armstrongoffer a novel vision of art as a "therapeutic medium," set within new spaces designed for self-discovery that encourage us to make "better versions" of ourselves. Among the existential and practical questions in the book, (including such significant queries as “What is the point of art?” or “What is it like to be a good lover?”), the book asks how and why we buy art and what this might mean for our emotional and psychological health. Here, we’ve excerpted their take on what galleries and museum gift shops should look like and why the roles of art dealer and head shrinker may not be so different.

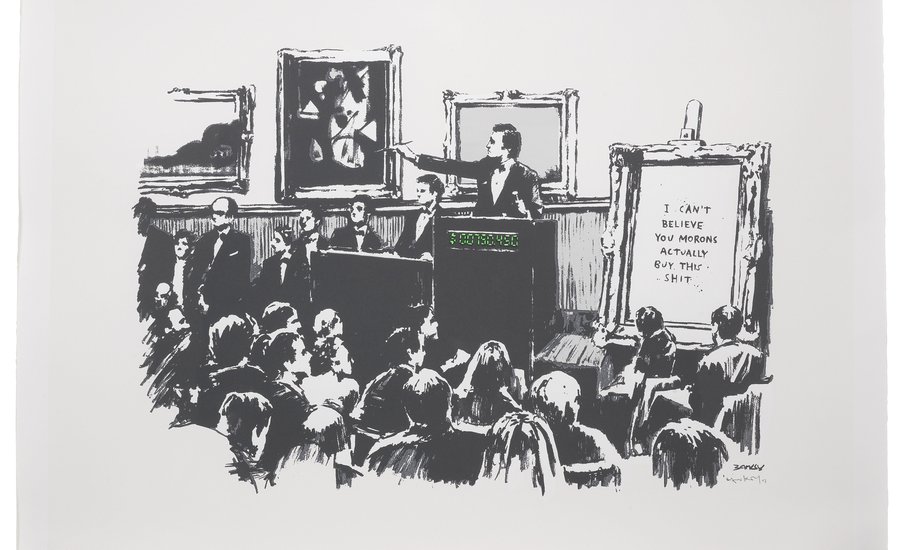

Whatever the possible problems with museums, few people could accuse them of consciously practicing deception or fraud. Not so with art dealers, who have been routinely accused of both ills for two centuries or more. But we shouldn’t blame the dealers. The problem with the art market must ultimately be located with the buyers: it is because so many don’t know what they are looking for that they can let themselves be swindled and led astray.

The task of the private gallery is a serious one: to connect purchasers with the art they need. The chief skill required for running a gallery should therefore be not salesmanship, but the ability to diagnose what is missing from the inner life of the client. The art dealer should strive to identify what kind of art a person needs to rebalance themselves, and then meet that need as efficiently as possible.

The key activity of a dealer would be to conduct consultation sessions that would reveal the state of the client’s soul. Before one can know what someone should buy, one has to know who they are, and, more importantly, what areas of their psyches are vulnerable. The role of the dealer would overlap with that of a therapist. The standard layout of a commercial gallery would evolve to include a therapy room, which one might need to pass through before getting to see any works for sale. Thus the dealer would operate as a matchmaker, bringing together an inner need of the client with a work best able to assuage it.

Today, this would look like a very strange process for buying and selling because we have the wrong picture of what art is. At present the task of the gallery dealer is to convince the client that a given work has a special kind of prestige: public but elusive, tangible yet confusing for the uninitiated. Such prestige is essentially dependent on what other people are thinking. The suggestion is always that if you buy this work, art-world insiders will approve. Hence, galleries seek to create an atmosphere that combines exclusivity and the sense of being at the cutting edge; that is, they build on our anxieties about being an outsider or old-fashioned. But galleries could get involved in a more important type of business. They could set out to help clients live better lives by selling them the art they need for the sake of their inner selves.

Largely on grounds of cost, most people don’t buy art in galleries. The chief vehicle for selling art on any mass scale is the museum gift shop. This is quite simply the most important tool for the diffusion and understanding of art in the modern world. Though it appears to be a mere appendage to most museums, the gift shop is central to the project of art institutions. Its job is to ensure that the lessons of the museum, which concern beauty, meaning, and the enlargement of the spirit, can endure in the visitor far beyond the actual tour of the premises and be put into use in daily life.

Claudia Angelmair, Betty, 2008.

Claudia Angelmair, Betty, 2008.

The means deployed, however, may not always be on target. Apart from books, gallery gift shops usually sell postcards and associative objects. Postcards are successful and important mechanisms for improving our engagement with art. Our culture sees them as tiny, pale shadows of the far superior originals hanging on the walls a few meters away, but the encounter we have with the postcard may be deeper, more perceptive, and more valuable to us, because the card allows us to bring our own reactions to it. It feels safe and acceptable to pin it on a wall, throw it away or scribble on it, and by being able to behave so casually around it, our responses come alive. We consult our own needs and interests; we take real ownership of the object, and, since it is permanently available, we keep looking at it. We feel free to be ourselves around it, as so often, and sadly, we do not in the presence of the masterpiece itself.

Gift-shop managers have discovered that people also like to buy objects heavily decorated with names of artists and their works, so we have Picasso table mats and Monet tea-towels. Such objects try hard to pay homage to artists. They would like to beautify the world and carry the message of artists deep into our homes, so that the spirit of Monet would be alive when we prepared the morning tea and Picasso would be with us as we mopped away the orange juice from the kitchen counter. The ambition is noble, but its method of execution is perhaps less so. The objects in a gift shop do have a faint link to the names they honor. Monet may well have liked tea towels, but it is unlikely that he would have wanted one with his own painting printed on it. The spirit of his best works of art, the things we love in them, may be much more consistent with, for instance, a completely plain and beautifully textured towel. This is more truly a Monet towel than one with his name on it. The point is not to surround ourselves with objects that carry the actual identity of the artist and his or her work. It should be to get hold of objects that the artists would have liked, and that are in keeping with the spirit of their works; and, more broadly, to look at the world through their eyes, therefore staying sensitive to what they saw in it.

One can imagine a different range of products to sell in the world’s gallery gift shops: objects that are aligned with the values and ideals of artists, rather than merely with their identities. The urge to buy something at the end of a museum visit is a serious one because it involves an attempt to translate a sensibility we’ve come to know in one area—on landscape canvases, portraits of ladies with parasols, and so on—and carry it over into another part of life, such as keeping the kitchen clean. This points to the heart of what museums should really be about: giving us tools to extend the range and impact of what we admire in works of art across our whole lives. This is why the gift shop is, in fact, the most important place in the museum—if only its true potential could be grasped and made real.