Here’s a quick primer by the writer and curator Jens Hoffman on the freewheeling and oh-so-of-the-moment Brazilian sculptor Alexandre da Cunha, excerpted from Phaidon’sVitamin 3-D: New Perspectives in Sculpture and Installation. For more from this formal nonconformist, stop by Thomas Dane Gallery in London before his show “Free Fall” closes on March 5th.

The London-based, Brazilian-born artist Alexandre da Cunha takes a transcontinental approach to artmaking; he takes a neoformalist aesthetic that has emerged in Europe and North America over the last five years and fuses it with a specifically Latin American artistic sensibility that is based on a post-Duchampian alteration of found objects. His work moves back and forth between the classic European legacy of modernism and a Brazilian incarnation of the same tradition. The latter has had tremendous influence not only on Brazilian visual art but even more famously on the country’s architecture; Brazil’s Neo-concrete movement of the 1960s aimed to rejuvenate the individual’s relationship to the surrounding world, and its legacy is still visible all over Brazil today.

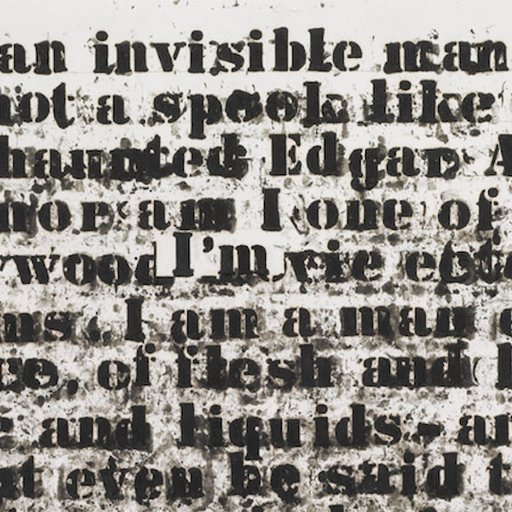

Alexandre da Cunha's Portrait, 2009

Alexandre da Cunha's Portrait, 2009

But in contrast to those Brazilian forebears, for whom slogans and ideologies played an important role, da Cunha describes his practice as being more about techniques and materiality. Context is also crucial; he is deeply interested in the history and setting of modern and contemporary art in Brazil, particularly the fact that core aspects of Brazil’s cultural identity are cannibalized from other cultures. He continues this tradition through the objects he chooses to appropriate—an act he describes as a “tropicalization” of the readymade.

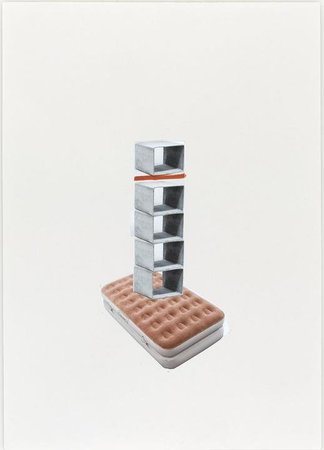

Alexandre da Cunha's Monumento VIII, 2010

Alexandre da Cunha's Monumento VIII, 2010

Most of da Cunha’s works originate from intense observations of the everyday—specifically the ways in which people in Brazil improvise ordinary objects to create other useful items. He translates these improvisations into his own sculptural pieces through processes of decontextualization and modification. The resulting artworks, made out of inexpensive and sometimes defunct consumer items, often mimic modernist sculptures, yet their forms are rooted in everyday life.

One of his best-known series, for instance, is a group of large ceiling-fan sculptures made from old skateboards and household utensils. Their titles are based on either the brand names of the skateboards or writings that their former owners scrawled onto them. The ceiling fan is obviously a reference to the climate and ordinary household decor of tropical countries such as Brazil. But da Cunha’s approach to appropriation goes beyond the straightforward reuse of the objects themselves. The found boards have scratches and stickers that tell stories—personal narratives of their former owners—and as cultural artifacts they refer to a particular lifestyle that is familiar to some and completely mysterious to others. We may see them as abandoned trophies, or fragments of secrets that da Cunha has found and exposed.

Alexandre da Cunha's Beach Towel, 2013

Alexandre da Cunha's Beach Towel, 2013

Recently, the artist’s work has become more political and critical. For his 2006 Velour Series he used metal fittings and tape to cobble beach towels, curtain poles, and ribbons into flaglike constructions. The towels’ graphics are carefully selected; they show, for instance, tigers or girls in bikinis. Thus the flags are critical dissections of the idea of national identity, playing on the stereotypical iconography of tropical or “exotic” countries by presenting lighthearted images associated with leisure culture as if they were official national symbols.