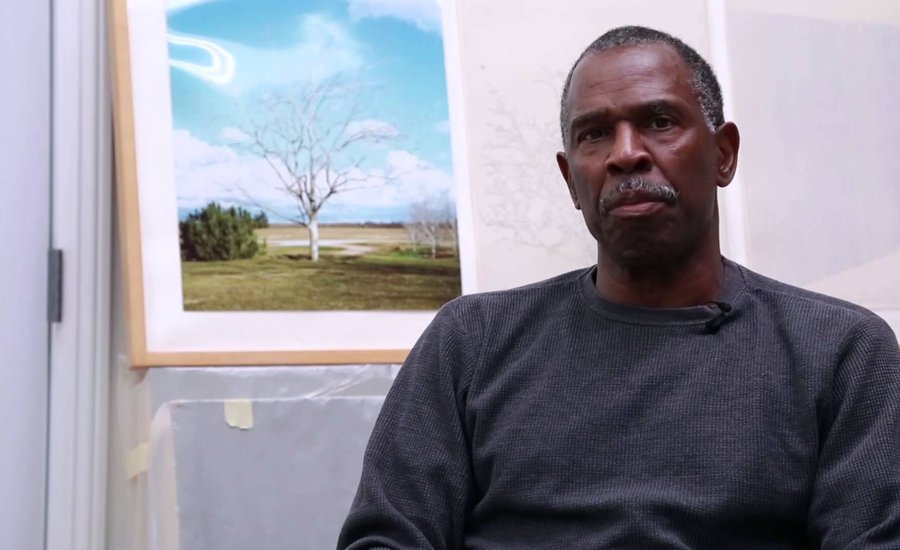

With four decades of art-making under his belt, LA-based artist Charles Gaines knows a thing or two about what it takes to be a successful—and morally aligned—artist. As last year's recipient of the CAA Artist Award for a Distinguished Body of Work and just coming off a solo show at Paula Cooper, Gaines continues to lead in conceptual art (and in the classroom) with an attention to language, communication, and political-aesthetic relations. In this excerpt from Phaidon’sAkademie X, Gaines shares his words of wisdom on how to be a radically righteous artist.

I cannot remember when I first started looking at art; some time in elementary school. Unlike today, art was taught as a special primary subject as early as the second grade. I attended an art high school and studied art as a concentration. I understood the history of art and contemporary art at that time (1959–62; I finished high school in three and a half years instead of four). We were taught the aesthetic values of early modernism and introduced to Abstract Expressionism. Of course, things have changed tremendously since that time. Picasso’sGuernica was introduced to the world not long before I was born. We have moved from early modernism through Abstract Expressionism to Pop, Minimal, and conceptual art, the period of high modernism and the avant-garde. I started my practice in 1972 as a second-generation Conceptualist who was not only involved with the critique of European modernism in the way the Pop artists were, as well as the Minimalists and conceptualists, but also investigated strategies that were later identified as postmodern. Also, I lived through a time that moved from a situation where women and minority artists were hardly, if ever, exhibited and represented by mainstream galleries to that of today, when their representation is fairly healthy. Thus I experienced the “Pictures Generation” and the rise of feminist art, all the way to the “post-black” era identified by Thelma Golden.

WHAT AN ARTIST SHOULD DO EVERY DAY

An artist needs actively to produce work.

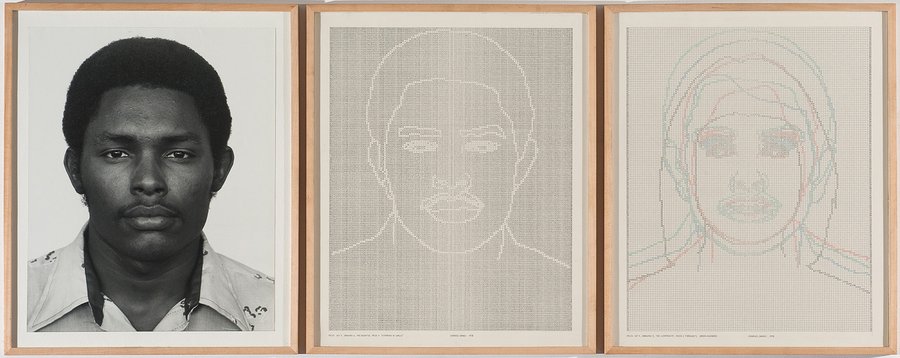

Faces, Set #4: Stephan W. Walls, 1978

Faces, Set #4: Stephan W. Walls, 1978

READING ABOUT ART

Most of my reading is not about art per se, though it may address it in some cases. My practice is heavily invested in critical thinking, so I began to read criticism and philosophy while a graduate student. I believed that art is part of the system of the production of knowledge, whether it’s about art or about other parts of our culture. For this reason, I believed that artists must always adopt a process of critique through their work, either of art itself, or by using art to find the limits of our understanding with respect to the subjects that make up culture. This is best done by exploring the ideas of others, which takes one out of the limits of one’s own habits and imagination. That is why reading is important. My ideas about the world are pushed by the intellectual explorations of others, where I am often taken to areas that I would never find on my own. Teaching is very connected to my studio practice because through engaging the minds of students I am able to find a community context for investigating ideas and concepts. My readings have focused on Marxism, semiotics, and post-colonial theory. Recently I’ve been doing readings on cognitive linguistics, the area of linguistics started by Roman Jakobson. My work is about the investigation of language as a subject and how language itself informs the way we understand the world. I pay particular attention to our political understandings and interrogate existing theories of aesthetics by pointing out the relationship between aesthetics and politics, where notions of individualism connect with ideas of culture and community. Therefore I do some reading in political theory.

George Kubler’s The Shape of Time made me think differently about art and challenged a few of my assumptions.

MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES

One has to have good technical knowledge, but by this I do not mean learning the techniques of drawing and painting. Those skills may be useful to those who want to draw and paint. I do not believe that there is a basic formal technical language that applies to all types of art practices—silly things like principles of design, or theories and rules of composition. Those areas reflect only a certain type of practice that existed between the 1800s and the 1900s. And I’m opposed to the idea that this technical knowledge is foundational, based upon the spurious assumption that describes art as being formed by a type of historical time similar to the organic model we find in genealogical studies. This approach looks at art in terms of particular genres and practices, forming an idea that, for example, modern painting creates a relationship between certain techniques and subjects that are so fundamental they put into play an inexorable history that as artists we cannot help but be a part of. This would mean that any new idea about art has to evolve from the limits established by the formative stage of art. This may be true if we are doing something that we call a “painting,” but it has nothing to do with the idea of art itself. Because of this, what one needs to know technically depends on what one wants to make as a work of art. In this respect, the technical vocabulary is so vast that one cannot learn all there is in order to be prepared to make any kind of art. And there is no shared technical vocabulary between these varied practices.

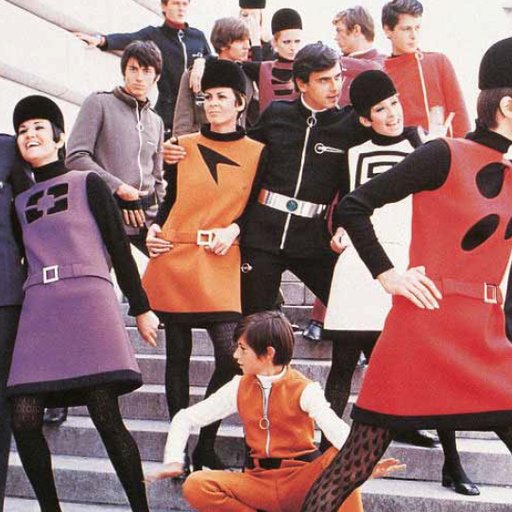

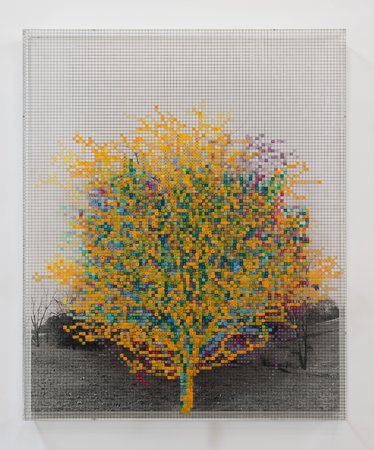

Numbers and Trees V, Landscape #8: Orange Crow, 1989

Numbers and Trees V, Landscape #8: Orange Crow, 1989

It’s been my experience that different artists have learned different things about art and they bring these things into their practice or they reject them. Certainly potential development of one’s work is informed by one’s training, but there is no universal training, nor can there be. If art is led by ideas rather than particular disciplines or techniques (i.e., a prescribed visual language), then artists learn what they need to know technically to execute their ideas, or they hire people to do it who have the expertise. The emphasis on an art that is idea-driven is very important in order to maintain diversity in artistic practice and so that art is useful as a tool to produce knowledge about the world.

ART AND MORAL RESPONSIBILITY

There aren’t too many dos and don’ts in my classes, but at the same time art is not exempt from moral responsibility. Don’t do anything illegal or that can hurt someone. Don’t use your art to exploit or as a tool to advance racism, homophobia, or sexism.

ARTISTS AND COMMUNITY

The Western tradition has produced an idea of art that does not favor the idea of community. We have inherited a couple of ideas of artistic practice that reflect this: one is aesthetics, where the artwork is considered uniquely as an aesthetic object; the other is generally the basic idea of the modern. In this case, art is one of the most recent examples of modernity, where it exemplified an alternative to the belief in reason that the Enlightenment championed. Here we find a suspicion of those things necessary for community: language, politics, and ethics. Hence art practice was considered to function beyond the range of representation, existing ontogenetically at the core of the human unconscious, revealed through acts of expressivity, or, as Baudelaire suggested, in the fugitive terrain prior to the imagination’s ability to give form. These ideas, as well as the idea of aesthetics itself, provide no agency for the collective notion of community and no means for advancing ethical judgments.

In this case, art exists in the laissez-faire area of the human will, forming a history and organizing culture in much the same way that capitalism does. But, just as capitalism asserts, human value interferes with its operation. I regard community to be a situation where the collective has the ability to regulate ideas coming from individuals—not to censor them, but to find ways that allow their implementation culturally. The way in which artists pay attention to other artists is by critiquing their works. An awareness of others’ works is not simply “paying attention”; it is the engagement with these works within a discursive field. Otherwise, paying attention would only serve the interest of the commodification of art objects because in this “paying attention” one is not required to think but only to experience.

The advantage of engaging with the works of others discursively is that the process builds human agency, which is necessary in any process of knowledge production. This is how art produces new ideas about itself and the world. This goes beyond the issues of influence—i.e., the idea of artistic community based on genealogical sequences of influence. I’m arguing for a particular type of engagement that bridges the ephemeral constructs of modernity and the ethical considerations of politics.

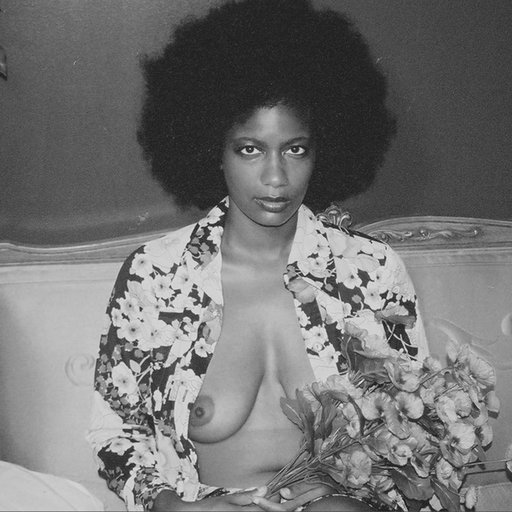

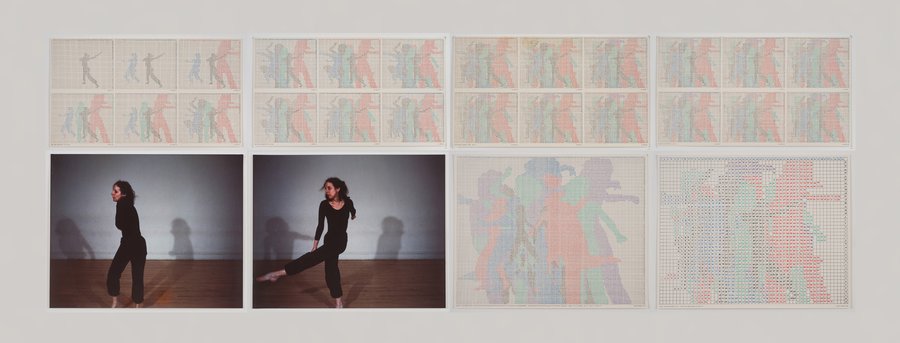

Motion: Trisha Brown Dance Set #11, 1980-81

Motion: Trisha Brown Dance Set #11, 1980-81

LIFE AS A PROFESSIONAL ARTIST

Right now, I’m really concerned about how much young artists are consumed with issues of career. Fundamentally, career—meaning the popularity or success of an artist, or ability to become famous and even rich—has little to do with art. Our culture uses the capitalist model to disseminate works of art and to provide income for artists. Many artists feel that career success is the measure of the significance and quality of artistic work. I believe this is a misconception. If you look at art as an arc of thirty to forty years instead of the three to five years that forms the perspective of the young artist, one sees that there is no consistency between the ideas an artist produces and the success or lack of it that he experiences. And because predictions don’t work in the case of art, we find a gamut of career possibilities, from artists who are famous and good, to artists who are famous but not very good, to famous artists who are wealthy, to famous artists who are poor. And then there are those artists whose careers look like a roller-coaster: here today, gone tomorrow.

PRACTICAL ADVICE FOR YOUNG ARTISTS

The one piece of advice I would give is to make sure to keep a detailed and accurate archive of your works. Do not rely on others to do that for you.

ASSIGNED READING

This reading list is comprised of books that create the content framework for most of my teaching. They also serve as critical interest in my own practice.

- Adorno, Theodor. Ästhetische Theorie. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1970. Translated by Robert Hullot-Kentor as Aesthetic Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

- Eagleton, Terry. The Ideology of the Aesthetic. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 1990.

- Fanon, Frantz. Les Damnés de la Terre, with preface by Jean-Paul Sartre. Paris: Éditions Maspero, 1961. Translated by Constance Farrington as The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press, 1963.

- Ranciére, Jacques. Malaise dans l’Esthétique. Paris: Éditions Galilée, 2004. Translated by Steven Corcoran as Aesthetics and its Discontents. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2009.

READ MORE FROM AKADEMIE X ON ARTSPACE:

6 Art-World Lessons From the Unorthodox Classroom of Akademie X

Chris Kraus on the Ambiguous Virtues of Art School

Words to Live By: Marina Abramović's Mystical Maxims for Artists

Venice Biennale Representative Joan Jonas's Workout Regimen for Artists

The Four-Hour Art Week? Read Carol Bove's Self-Help Guide for Artists

Sanford Biggers’s Tough-Love Guide to Surviving the Art World

Go On a New York City Scavenger Hunt With Artist Mark Dion

Ólafur Elíasson’s 9 Foolproof Tips for Urban Inspiration

Painter Carrie Moyer on Her Polyamorous Relationship With Art

Wangechi Mutu’s Words of Wisdom for Struggling Artists