Phaidon’s new compendium Vitamin P3 is a critical window into the latest developments in international painting, so it makes sense that most of the 108 artists profiled tend towards the youthful (nearly half are under the age of forty—see our statistical breakdown of the book here for more data-driven fun).

At the same time, the past several years have seen the rise of the “ elder emerging ” category—older artists who, often for reasons of gender, race, location, or subject matter, have been looked over or excluded from the canon of their respective generations and are only now being recognized for their contributions to their medium. The new edition of Vitamin P includes no fewer than 18 painters born before 1960, each actively engaged in expanding and developing their studio work into very different directions. As you'll see below, their paintings are as fresh and surprising as the works of artists half their age, with the added benefit of the years spent honing their craft.

We’ve already interviewed P3’s oldest painter, Etel Adnan (born 1925); here, we’ve excerpted the entries for three of her fellow P3 seniors from around the world.

Marwan

Born 1934, Damascus, Syria. Lives and works in Berlin.

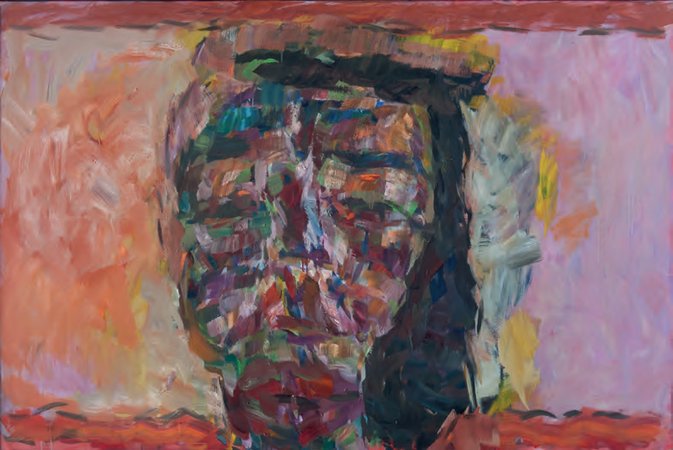

Marwan Kassab Bachi (known simply as Marwan) is the kind of painter whose existence is justified through the act of painting, and whose painting is solely reliant on this continued and necessary justification. Painting since the 1950s, Marwan’s practice is defined by an impassioned, continual process of internal burrowing. This intangible impulse to locate and translate an inner state of being ties together a neo-expressionist perspective on the healing properties of art and painting, with Sufic notions of the infiniteness of the self. Born in Damascus in 1934, Marwan moved to Berlin in 1951 when he was twenty-three to study painting at the Academy of Fine Arts. Having lived through the Syrian Republic’s fight for—and transition into—independence from the French, granted in 1941 and finally realized in 1944, and having witnessed Germany’s post-Second World War processes of rebuilding and unification (including the tearing down of the Berlin wall in 1989), Marwan articulates an Arab-European perspective of geopolitical shifts and trauma during his lifetime.

In his early work from the 1950s, figures and faces appear with distinct features, often identifiable as political or intellectual characters from the Middle East, such as the 1965 portrait of Munif al-Razzaz, former secretary-general of the Syrian Baath Party. A literary approach to subject plays out through densely layered oil paint applied with thick strokes. Delicate yet heavily concentrated surfaces—in texture, color and subject—express struggle and sorrow but with vitality and movement. Since the 1970s Marwan has engaged in a more exaggerated, abstracted figurative language where the face, the body, and its intricacies frequently reappear, such as a frown, a pursed mouth, or hanging limb—glimpses of introspective expressions of humanity’s inner self.

In multiple works titled Head , Face , or Figuration , the body or the face are distorted, with deep set eyes or disproportionate limbs and exaggerated heads stretching across the canvas. There is a concentration of subject and a focus on editing, whether the face, the look or the gesture. The breadth of expression in these large paintings is vast, especially considering the close proximity of the subject. Often his characters give a sideways glance, an over-the shoulder or downward look of uncertainty or disdain, with the gaze eerily staring the viewer down from all angles. These capture the awkwardness of the body and the uncertainties with which minds manage their movements and expression. In this new kind of abstracted, figurative realism, the body or the face and landscape blend in and out of each other, with a muted color pallet of browns, greens, and reds.

– Laura Barlow

Rose Wylie

Born 1934, Hythe, Kent, UK. Lives and works in Kent.

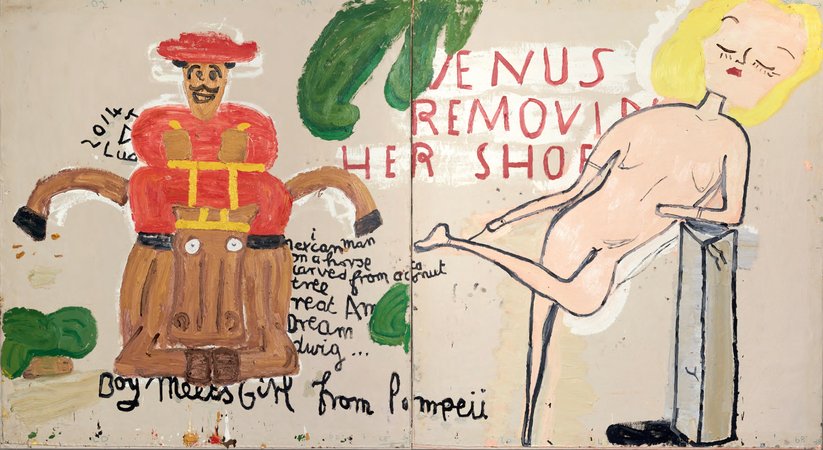

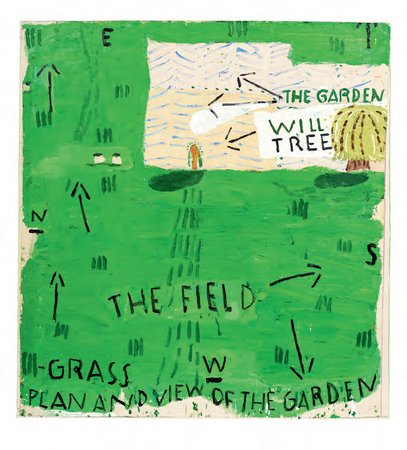

It is an historical fact that what originally prompted many modern artists to paint in a naive, elementary way was mostly a conflictual relationship with the concept of representation—an urge to challenge the status quo by making things that wouldn’t meet the accepted standards of what was considered aesthetically valid or valuable. Rose Wylie’s paintings are childlike, direct, simple, and uncommonly appealing, but they come from observation rather than confrontation. A twenty-year long hiatus from art to raise her children in what is normally considered a pivotal moment in a career—something the most career-driven spirits might find difficult to understand—enabled her to enjoy her family and reprise painting with a more mature understanding of the medium and without any pressure. As she once remarked, “If you get recognized just out of art college, you’ve got to work with that reputation and the misery of whether you can keep it going or not. You do stuff according to what people want to buy, and that’s the worst thing. That’s why I always thought Madonna was so good, because she did something quite different and occasionally quite shocking.”

Wylie’s reference to Madonna, while a little unexpected, leads to the second significant benefit that resulted from her voluntary break: the possibility of experiencing firsthand ordinary circumstances at a convenient distance from the dynamics and the politics of the art world—an occurrence that would leave her fresh, unjaded, and with an open mind, and that eventually would enter her work in the form of frequent but subtle references to sport, cinema cartoons, and other forms of popular culture. The television and newspaper characters that permeate her paintings do not provide social commentary—they are there because of their intrinsic worth in the eyes of the artist or for their visual quality. The difference between what is reality and what is painted as real is at the core of Wylie’s work, and it manifests itself through a rejection of mannerism and a heavy reliance on spontaneity. The extra pieces of canvas carrying additional signs or colors that are stuck over some of her paintings are evidence of the constant revisions that take place in her compositions; but whereas for artists like William Kentridge (b.1955) erasures are made visible to signify movement, in Wylie’s case they tell of the journey into the unknown that she undertakes at the moment of making her work.

Unfazed by the idea of publicly taking pratfalls and unapologetic about pointing out how excessive knowledge can at times be more of a limitation than an asset, what Wylie ultimately lets transpire in her paintings are the decisions that never stop coming, the honesty of her images, and the certainty that being skillful has nothing to do with getting what you want, but with how well you get it.

– Michele Robecchi

Arpita Singh

Born 1937, Baranagar, West Bengal, India. Lives and works in New Delhi.

Arpita Singh’s paintings often mingle cheerful chaos with ominous confusion. Munna Apa’s Garden (1989) is littered with multiple narratives: a severe lady waters her plants, a couple take a ride in their car, an aging woman gazes forlornly from a window. Each of these characters is trapped in their own private world. Threaded through their stories are fighter planes, a toy car (which looks like it has escaped from a child’s sketch book), blood-red petals, and an armchair (or is it a cloud?). Meanwhile a boy, with his eyes shut, floats in electric-blue space. Is he dead or sleeping? On one side of the canvas, a young girl pokes her head out of a rose-patterned curtain. She seems puzzled. Does she stand in for the perplexed viewer of Singh’s compelling clutter?

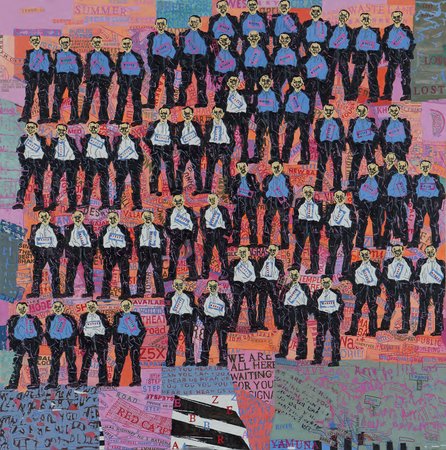

Born in 1937 in West Bengal’s Baranagar (now Bangladesh), Singh worked as a textile consultant at the Weavers’ Service Centers of Kolkata and Delhi. West Bengal is famous for its densely patterned kantha embroidery, which intertwines colorful creatures from folk tales with figures from Hindu mythology. Much like kantha -embroidered quilts, Singh’s paintings also swirl with a myriad of motifs. Moreover, the feel of textiles permeates paintings like Zebra Crossing: We are all waiting for your signal (2011), which resembles a homemade wall-hanging—albeit a somewhat sinister one. Here, identically-clad, black-suited men congregate: they stare out of the picture as if looking to the viewer for instruction.

In the 1980s, Singh was part of a group of women painters – including Nilima Sheikh (b.1945) and Nalini Malani (b.1946)—who highlighted gender issues in their work. Singh’s watercolors , such as Woman in an Embroidered Veil (1987), are typical of this period. Here, a damsel is draped with pearly-white cloth, bedecked with roses. Is the imprisoning material a funeral shroud or a wedding veil? Are the flecks of crimson that surround the woman meant to be bridal confetti or drops of blood? Unlike Malani and Sheikh, who went on to explore the female form outside the conventional picture-frame, Singh chose to stage a quiet revolution within the traditional parameters of the medium. Sheikh is known for her Persian-inspired panoramic, double-sided painted scrolls, which dangle from the ceiling, and Malani for her “video-shadow plays,” in which folk and fairy tale figures are painted onto revolving plastic cylinders, simulating magic lantern displays. In contrast, Singh chose to stick more closely to the conventions of painting and, by the 1990s, started to use oil paint as well as watercolor to portray her female protagonists.

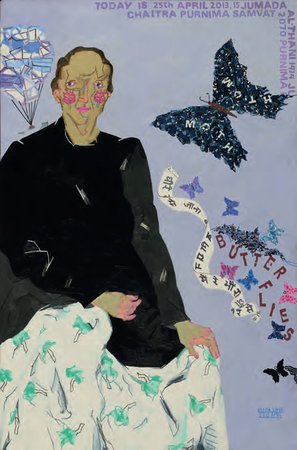

In The Moth (2013), black moths and iridescent butterflies quiver in a lilac sky. At the top of the picture are the words: “Today is Chaitra Purnima.” Chaitra is a month in the Hindu calendar associated with spring. However, Chaitra Purnima is a festival that pays homage to the scribe of Yama (God of Death). Fittingly, a black-clad female—with pretty pink roses on her checks—looms large. Like the insects, the protagonist has a dual significance: giver of life and harbinger of death. Letters spelling the word “butterflies” are jumbled together. The words look like they have been stenciled in; the lepidoptera as if they have been stitched on; the painting mimics a patchwork quilt for a girly nursery. The Moth combines Hindu mythology with feminist themes, forging ties between art and craft along the way. The result? Although Singh has stuck within the bounds of the traditional picture frame, her experiments are no less far-reaching than the less conventional work of some of her contemporaries.

– Zehra Jumabhoy

Other excerpts from Phaidon's new Vitamin P3 include the exciting world of Post-Canvas, freeform art ; Glitter, Neon, and Good Old Fashioned Paint: Three Abstract Painters Pushing the Medium Forward ; and Three Emerging Painters Changing the Way We See Ourselves .