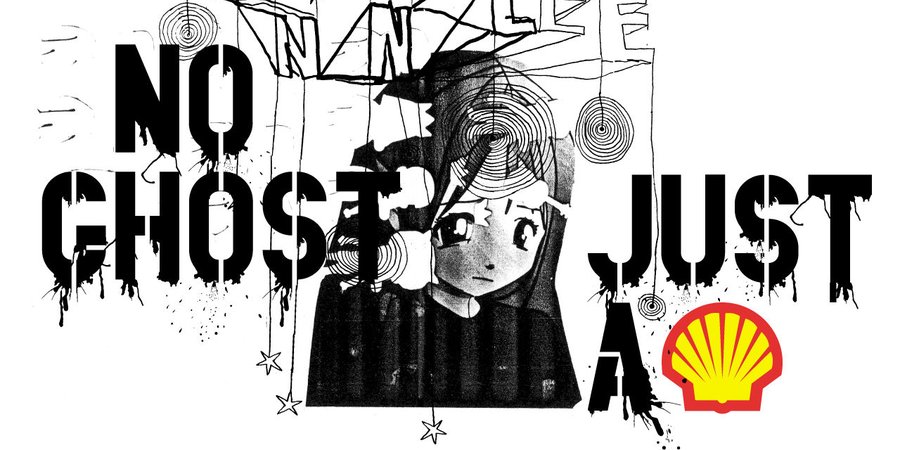

Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno are among the most important French artists working today; with a major installation just closed at the Park Avenue Armory (Parreno) and a special Roof Garden commission still on view at the Met (Huyghe, in addition to recent retrospectives at LACMA and the Pompidou), the pair have already ascended into the lofty heights of the art establishment. In this essay by Hans Ulrich Obrist, originally published in Phaidon’s Defining Contemporary Art, the esteemed curator discusses No Ghost Just a Shell, the groundbreaking collaborative work that put the pair on the map and introduced the art world to AnnLee, one of the art world’s most famous fictional characters of the early aughts.

No Ghost Just A Shell began as an idea by Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe to invent a new way of working together, further pursuing the reflection-in-action they had been developing since the early 1990s, through what Douglas Gordon calls a “promiscuity of collaboration.” Whereas their earlier collaborative projects had entailed working together with regard to a given context (an association, a film, an exhibition, a book), No Ghost Just A Shell was more than a context. It was a sign, offered up to different artists to read and interpret successively and separately, each following his or her own inclinations.

This approach ran counter to a prevailing rule of the art world. Traditionally within artistic production, the idea is legitimated by the definition of a form, then protected by a system of copyright. Here Parreno and Huyghe sought a different approach. First, each collaborating artist had to produce a different image on the basis of the same idea; second, the form each artist gave to this idea would not be definitive but would serve as a catalyst for the following work; and finally, copyright would no longer be attributed to the authors but to the sign itself.

Following Huyghe and Parreno’s purchase of the cartoon character AnnLee from a Japanese manga company, No Ghost Just A Shell became a succession of pieces beginning with a poster designed by M/M (Paris), and followed by films made by Parreno, Huyghe, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Liam Gillick, and others. Further diverse projects emerged by Mélik Ohanian, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Pierre Joseph, Joe Scanlan, and others. Gradually the world of AnnLee began to take shape and the numerous questions raised by its authors slowly linked together – questions on the status of the image, of representation, of beings in the world of the character, and on the very polyphony of the work. Perhaps above all, the question for these artists became, “How can a community constitute itself on the basis of the same sign, identifiable to all, yet peculiar to each person?”

Meanwhile, for the immunologist and specialist in “programmed cell death” Jean Claude Ameisen, whom Parreno and I interviewed in connection with No Ghost Just A Shell, the project raised profound questions about the constitution and continuity of the existence of the individual. Ameisen used his work to throw light on the questions raised by the artists and also took advantage of the imaginary construction that they offered him to carry his thought to extremes, which is not always possible in the study of living creatures alone. “The problem with living creatures is that it is very difficult to die when one is not alive,” Ameisen said at first. Then, after having pondered this stumbling block and thought about whether AnnLee had the characteristics of a living being, he finally said, “When it comes to it, the question is not, ‘Is AnnLee alive or not?’ but rather, ‘Can something live without death being present?’”

The exhibition “No Ghost Just A Shell” at the Kunsthalle Zürich in 2002 finally brought together all the projects by the collaborating artists. In the end it was thanks to this dissemination in time and space of AnnLee’s temporary appearances that the idea ceased to be just a jolie idée (a nice idea). More than a coherent association of pieces, No Ghost Just A Shell became an experimental exhibition concept in its own right. The purchase of the entire exhibition by the Van Abbemuseum in 2003, and then in a second version by the Miami-based collectors Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz, is itself an event of considerable historical significance, being a very rare instance of the collecting of an exhibition rather than the separate sale of its component artworks, whether by a public institution or a private collector (in this case, both). What is at stake in the purchase of the collective “No Ghost Just A Shell” exhibition is, then, the idea of No Ghost Just A Shell as an archive on the one hand but, on the other, also as a disseminator of information – where historic information contains seeds for the future while carrying the information of the past.

With No Ghost Just A Shell, Huyghe and Parreno truly invented a mode of art-making that defies the rules generally governing the circulation of contemporary art exhibitions. The project developed into an exhibition that would not, like most group shows, reduce complexity to a product or a cliché but would actually propose new temporalities. It opens up possibilities of sedimentation through space and time, of organic growth, and of the possibility that an exhibition might not be consumed in one visit but could become instead an ongoing, engaging experiment.