How could artists in the second half of the 20th century respond to the austerity and material purity of Minimalism that had swept America in the wake of Abstract Expressionism and at the tail end of the Modern period? What possible counter could there be for New York's particular breed of sculpture, in which the artwork was conceived as a hermetic physical presence, exemplified by the massive geometric fabrications of Richard Serra, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, et al?

In the 1960s, as Minimalism was quickly becoming the de rigueur style of American art's intelligentsia, another group of young artists across the country were engaging with the same stripped-down aesthetic ideals, but awash in Southern California vibes. Similar to the New York Minimalists, the Light and Space movement, as it is now known, was closer to a loosely defined sensibility than an organized collective. The term came to refer to the work of artists who playfully flirted with Op art, Minimalism, and geometric abstraction with an emphasis on transcendentalist levity, boundary-dissolving luminescence, and—in place of New York Minimalism's hard-edged industrial materials—an embrace of cutting-edge space-age fabrication methods.

The 1971 exhibition at the UCLA Art Gallery "Transparency, Reflection, Light, Space," which included works by Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, John McCracken, and Peter Alexander, was art history's formative introduction to the informal movement. But aside from James Turrell's popular maximalist light show at New York's Guggenheim Museum in 2013, wherein the artist transformed the museum's famous rotunda into a giant light installation, Light and Space, as a whole, hasn't been explored in a major exhibition.

More often, it's represented as a divergent branch of Minimalism rather than its own cogent strain of American art. Muddying the waters even more is the fact that many Light and Space artists were also included under the greater rubric of Minimalism and showed in exhibitions like "Primary Structures" in New York. Nevertheless, there are particularities to Light and Space that emphasize that the movement deserves a spotlight of its own.

SEEING YOURSELF SEE One of Doug Wheeler's "rotational horizon works" shown at David Zwirner Gallery

One of Doug Wheeler's "rotational horizon works" shown at David Zwirner Gallery

Light and Space artists embraced, rather than denouncing, the "theatricality" of Minimalist sculpture that critic Michael Fried described in his important 1967 essay "Art and Objecthood." Emphasizing an immersive interaction with the work of art that called dramatic attention to the personal experience of the viewer, Light and Space artists' creations ranged from the all-encompassing, mind-bending expanses of Doug Wheeler to sculptures made from materials that seem to change in appearance as the observer moves around them—or that use transparency and reflection to make ambiguous the relationship between the art object and its environment, as in Robert Irwin's transparent, effervescent constructions. Equally important, if lesser known, are Helen Pashgian's tubular sci-fi-esque columns, designed to be walked around by the viewer in succession.

In Light and Space works, neon, glass, resin, acrylic, and fluorescent lights—materials that were also used in Pop and Minimalist sculpture—frequently appear. But Light and Space artists used these materials specifically to emphasize how light reflects off of, passes through, or bends around them. As James Turrell said, in a frequently quoted aphorism, "There's a sweet deliciousness to seeing yourself see something."

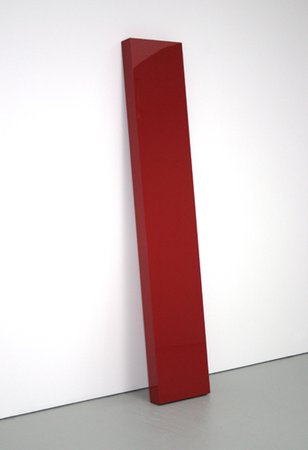

LET'S GO SURFING John McCracken's Vision, 2004

John McCracken's Vision, 2004

Whereas the east coast branch of Minimalism had ambitions to become a universalizing sensibility, Light and Space was indubitably tied to its foundations in California, and especially in Los Angeles. "California Minimalism" and "Finish Fetish" are both alternative names for the movement, and for good reason. The allure of waxed surfboards and gleaming automobiles in the California sun were aesthetic touchstones for the light, reflective, and visually beautific quality of Light and Space artists' works.

"Finish fetish" refers to the glossy finishes on, for example, the spray-lacquered plywood sculptures of John McCracken, who used fabrication techniques that were commonly used for making surfboards. Likewise, DeWain Valentine began his career working in boat shops. Reflective or transparent epoxy, lacquer, and plastic materials not only provide lustrous, lucid surfaces; they also act as screens that mediate the experience of the exhibition space, rather than defining it the way Robert Morris's minimalist boxes did.

SoCAL TECH Mary Corse's works displayed at Ace Gallery, Los Angeles

Mary Corse's works displayed at Ace Gallery, Los Angeles

After World War II, technologies and fabricating facilities that had sprung up to support the war effort were newly available for specialty manufacturers'—including artists'—use. These so-called "cottage industries" along the West Coast specialized in technologies, like vacuum-forming and fiberglass molding, that were put to use early on by companies like the publisher of artists' multiples Gemini G.E.L., as well as by individual artists. West Coast artists' pioneering encounters with such cutting-edge fabricating technologies directly influenced the mix of Zen and tech that gave rise to Silicon Valley's techno-organicism, evident in the designs of companies like Apple since the 1980s. The glowing white monochromatic objects made by Mary Corse, for example, which resemble pieces of a spaceship stage set, predate Apple's minimalist designs by several decades. Likewise, Larry Bell's translucent boxes wouldn't look out of place alongside high-tech accoutrements of the 21st century.

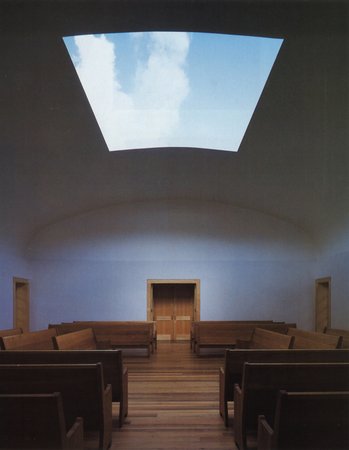

DIFFUSIONS OF LIGHT AND SPACE James Turrell's Meeting, 1986

James Turrell's Meeting, 1986

Light and Space proved to be a formative influence for many Post-Minimalist artists of the latter half of the 20th century as a way of charting alternatives to the dead-end finality of Minimalism, offering a natural pathway to postmodernist deconstruction. Artists like Judy Chicago, who is associated with feminist art and conceptualism in the '70s, actually got her start in making Light and Space-inspired fogged domes in Los Angeles. The movement's long-lasting influence is also present in the work of contemporary artists like Sophia Collier, whose convincingly aqueous-looking sculptures were shown at Art Basel in 2012. Meanwhile, an ever-popular permanent installation at MoMA PS1 in New York is James Turrell's Infinity Room, a simple and evocative piece made by cutting a hole in the museum's ceiling and leaving it open to the air. Although, of course, when the weather's bad—as it is for at least half of the year, here on the country's grayer coast—the piece must be closed to the public.