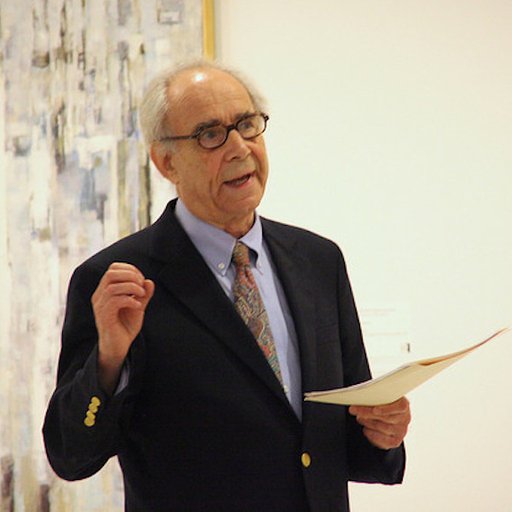

The reputation of the art critic Rosalind E. Krauss is the kind of paradox one only finds in the art world. Though the theory-heavy art journal she’s famous for founding—October—only has a circulation of about 2,000 people, and her myriad books and articles remain little-read outside of academic circles, she is considered one of the most influential critics of Modern and contemporary art of the past half-century. Most specifically, she’s credited with helping introduce the American art scene to French post-structuralist thinkers like Michel Foucault and Jaques Derrida in the 1970s and ‘80s, whose ideas have since become almost de rigueur for talking about and teaching art history in the 21st century (for better or worse).

The ideas in her work, however, and her influence on today's art community are intensely important to understand even if you're not about to wade into the Columbia University professor's scholarly oeuvre. For the time-impaired, here’s a quick primer on Krauss to get you started.

Beginnings

In her own recounting, Krauss has been both interrogating and defending Modern art from her earliest aesthetic experiences. After noticing that his daughter, who enjoyed painting as a child, had a predilection for art, Krauss’s father encouraged her creative side with regular trips to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (conveniently located near his offices at the Department of Justice, where he worked as an attorney). There, as Krauss recounts, the budding critic began honing both her eye and her tongue. “In the modern galleries,” Krauss writes, “my father would make objections to the works and I would defend them. I adopted a certain militancy, for I had to try to convince my father that these modern works of art were not phony, that they were really important. This sharpened my desire to explain.” Works by Paul Klee, Georges Braque, and Mark Rothko proved especially influential on the young aesthete, and helped form her thinking.

By the time she arrived at Wellesley College as an art history undergrad, this early appreciation for Modernist masters had blossomed into a full-blown love affair. It was in the context of her senior thesis on Willem de Kooning that Krauss found herself seriously engaging with the work of Clement Greenberg, the ultra-influential New York art critic best known for his strict formalist analysis, insistence on medium specificity, and championing of the Abstract Expressionists during their early days. This intellectual relationship shifted into a personal one following Krauss’s enrollment in Harvard’s department of fine arts as a PhD student, where she met and befriended Greenberg as she prepared her dissertation on the recently deceased AbEx sculptor David Smith, whose estate the elder critic helped to manage.

Breakages

The friendly dealings between these intergenerational critics proved short-lived. Krauss, who had been writing for such respected publications as Artforum since 1966 (only four years after graduating from Wellesley and three years before she received her Harvard degree), found herself increasingly interested in the work of Minimalists like Richard Serra and Donald Judd—artists Greenberg dismissed as not adhering to the strictures he laid out for Modern art.

For Greenberg, truly avant-garde art strove for an ever-increasing purity and adherence to the history its medium, a view Krauss eventually came to regard as overly simplistic. As she says, “[Greenberg’s] whole relationship to art was incredibly teleological. His idea was that art had to end up in a certain place, and if it didn’t contribute to that trajectory then he dismissed it.”

In the context of this opposition, Krauss began exploring novel avenues for evaluating works of art that seemed more true to her experience as a viewer. She eventually landed on the writings of French post-structuralists like Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes, incorporating their ideas on meaning and value as a subjective, historically contingent, and mutable phenomenon into her own writings on contemporary art. Freudian thinkers like Jaques Lacan also proved useful insofar as they theorized the repressed, often violent and sexual impulses that Krauss was coming to believe were vital to the Modern art she loved.

Far more than academic navel-gazing, Krauss and her contemporaries saw these ideas as intensely political and even revolutionary; as she wrote in 1972, “We can no longer fail to notice that if we make up schemas of meaning based on history, we are playing into systems of control and censure. We are no longer innocent.” Increasingly, the artwork’s medium became less relevant than the socio-political history surrounding and informing the work itself, a history that could be reframed by a sensitive and informed critic.

It’s precisely this spirit of revolution that lead Krauss to the next big break of her career: leaving the respected editorial board of Artforum in 1976 (she’d been promoted to editor in 1971) to start her own publication called October. The departure resulted from one of the great art-world controversies: when the artist Lynda Benglis took out a two-page advertisement in Artforumfeaturing herself naked but for sunglasses and a provocatively co-opted dildo—a response to what Benglis saw as the machismo of the male Minimalists encapsulated in a notorious photo Krauss herself took of the artist Robert Morris—Krauss condemned the magazine for allowing what she deemed pornography to "brutalize" its staff and readers, and left.

Co-founded with her Harvard classmate and fellow Artforum apostate Annette Michelson, the new journal took its name from Sergei Eisenstein’s classic 1927 film October: Ten Days That Shook the World, an avant-garde recounting of the Russia’s famed October revolution. Their goals for the new magazine were clear: provide an outlook for the then-nascent critical writings of the post-structuralist school in the American context.

As anyone whose taken an art-history class in the past two decades can attest, these thorny ideas (and the interpretive mode of looking at and talking about art they call for) have proven highly influential in the academy, where Krauss has spent most of her adult life—she’s been on the faculties of M.I.T., Princeton, Hunter, and finally Columbia, where she’s worked since 1992.

Both October and Krauss have earned reputations as highly progressive and eminently obscurantist, a reflection of their shared reliance on dense theory as a means of unlocking the art object. If you’ve ever scratched your head over a Derrida or Lacan quote in a press release or catalog entry, chances are good you have Krauss and her revolutionary little publication to thank. By the time contemporaries like Hal Foster began contributing to October, this decidedly postmodern turn had taken a firm hold on the artistic mainstream, setting the stage for the vibrant interpretive art culture we have today.

Books

While Krauss first achieved prominence for her articles in Artforum and October (many of which, such as her legendary "Sculpture in the Expanded Field," included her infamously inscrutable diagrams) her books have proven especially significant in establishing her place in contemporary art criticism.

Her 1985 collection of essays The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, for instance, takes the mythos of the historical avant-garde to task. Krauss claims that the developments of postmodern art theory call for a thorough reevaluation of Modernist masters like Rodin and Giacometti, as well as an overall overhaul of the ways in which we evaluate art to include (perhaps unsurprisingly) the analysis of the philosophers she admires. In contrast to claims about these artist’s boundary-breaking originality and continual inventiveness, Krauss finds repetition and reproducibility to be at the heart of their work, and positions it as a challenge to their late-20th-century celebrants, who are now tasked with proving the artistic value of their achievements through appeals to framing (both physical and metaphorical) or what she calls “the authorial mark of emotion,” better known as feeling.

Her 1993 book The Optical Unconscious expands upon the ideas of this earlier effort, turning to figures like Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, and Max Ernst as embodying a counter-narrative to the Greenbergian formulation of modern art. In short, Krauss argues that Modernism was in fact less concerned with purity and autonomy than previously thought, looking to movements like Surrealism and Dada as concurrent developments that take the subjective states of the unconscious as their inspiration and rationale, and drawing heavily upon the psychoanalytic theories of Freud and especially Lacan. The book is also notable for Krauss’s unusual, almost diaristic writing style, which underscores the intensely personal (not simply “pure”) motivations underlying the work.

Movingly, Krauss’s 2011 book Under Blue Cup also attempts to write theory through personal narrative, this time through the very specific lens of her 1999 brain aneurysm that left the intellectual temporarily bereft of her short-term memory. A central insight from her subsequent cognitive therapy—“If you can remember who you are, you can teach yourself to remember anything”—provides the occasion for a reappraisal of the artist’s medium as a form of memory. She looks to the work of artists like Ed Ruscha and Sophie Calle as exemplifying a way out of the so-called “post-medium condition” by turning to a new medium (cars for Ruscha, photojournalism for Calle, etc.) to act as structure and support for their ideas.

For younger artists still casting about for a new way to make their mark on art history, Krauss’s ideas should provide a welcome jumping-off point, as they have for an entire generation of art writers.

[related-works-module]