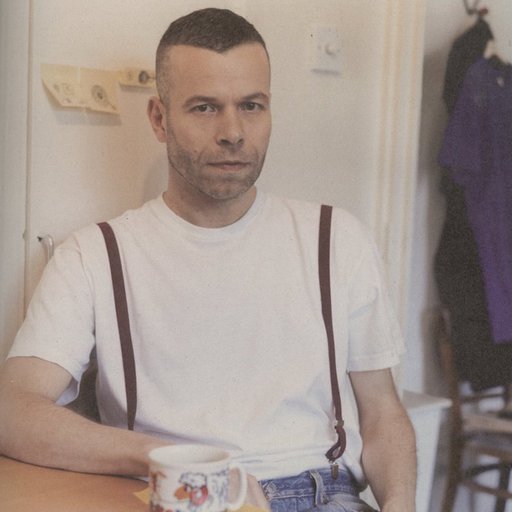

The German artist Isa Genzken has been lighting up Instagram accounts across the five boroughs and beyond since the opening of her new, mannequin-heavy show at David Zwirner. This isn’t her first time taking the Big Apple by storm; her 2013 MoMA retrospective was met with glowing critical praise, and she's had regular solo shows in top-tier New York galleries like Jack Shainman and Marian Goodman since 1989. In this essay, excerpted from Phaidon’s Defining Contemporary Art, the curator Bob Nickas takes us back nearly two decades to look at another of Genzken’s engagements with the city that never sleeps, her three-part collaged artist’s bookI Love New York, Crazy City from 1995-6.

One sunny afternoon in 1996, a woman came bouncing down the street, seemingly aware of everything along the way: newspaper vending machines, passing cars, people at sidewalk cafés, buildings up above. The woman was Isa Genzken, alive in New York. This was the year that she completed the third in a trilogy of collage books, I Love New York, Crazy City. Although she would refer to them as “guidebooks,” they were not meant to function as guides in the usual sense. Anyone who thought otherwise would surely find themselves lost, perhaps pleasurably so. The books came out of the many photos that Genzken was taking in 1995-96, a period when her art activity was limited by her situation: living mostly in hotels and roaming around New York, which in a sense became her city-studio. She has remarked, “I’ve often taken photographs when I don’t have a studio – for example, the Ohr (Ear, 1980) photos, where I took pictures of women on the streets of New York.” With these works, as with I Love New York, Crazy City, a disadvantage became, in effect, advantageous.

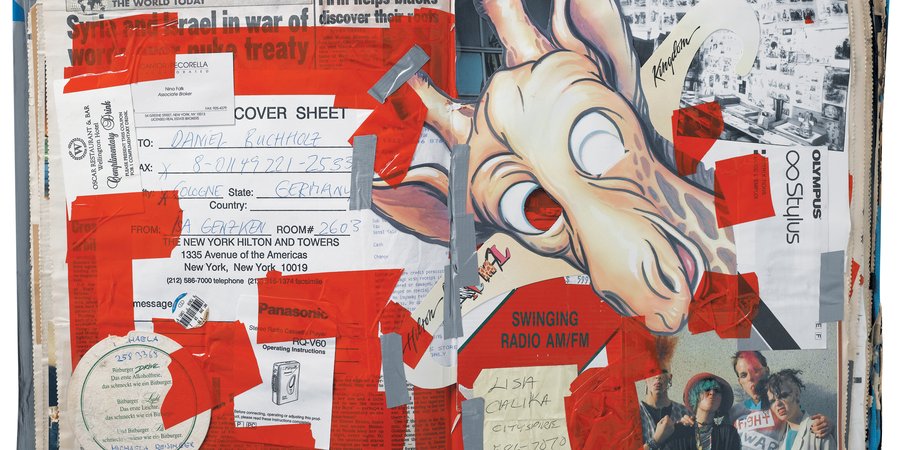

For Genzken, a German artist living for a number of years in America’s biggest city, taking pictures was and wasn’t the same as for a tourist, even an accidental one. She may have bought a postcard of the Statue of Liberty with the World Trade towers looming in the background, but she also examined the everyday, turning her camera on a couple in a dimly-lit coffee shop, or on an empty snow-covered parking lot, or taking notice of a sign behind a bar: “THE CUSTOMER IS ALWAYS WRONG.” Visitors on holiday often take home the playbill from a Broadway show; Genzken collects a business card for “dayglo aborigines,” a matchbook advertising an escort service (“Call the Coeds”) and a concert flyer: “COMING TO IRVING PLAZA ... MARCH 11 – SKID ROW … APRIL 2 thru 5 – FUGAZI.”

Here one pulls together the various threads that led Genzken, known primarily for her sculpture, to the form of this work, at this time and in this place. “To me,” she has said, “New York has a direct link with sculpture.” A common enough observation, to be sure, but then Genzken elaborates in an unexpected way. “I think that photography has a lot to do with sculpture – because it is three dimensional and because it depicts reality.” Of this last point there can be no disagreement, even where abstract photography is concerned. But when Genzken posits photography as three dimensional, you have to understand that she claims this not for photographs but for photography, meaning the activity pursued with a camera: using the camera as an extension of the eye and the body to capture the rhythm and movement of the world around us from moment to moment.

Accordingly, I Love New York, Crazy City can be seen as the storyboard for a film, and Genzken’s collage, with roughly applied silver duct tape or red transparent tape, is her means of splicing and montage. Recalling the filmic tradition of the “city symphony” (begun in 1921 with Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler’s collaboration Manhatta), it revels in the modernity of quotidian New York and in its inhabitants: the city as a stage on which to perform. In I Love New York, Crazy City, the city is the star of the “movie,” to be sure, but so too, particularly in the first two-thirds of the book, is Genzken. Wearing a fluffy ballerina skirt, she clowns around on a fire escape; disguised in hat and dark glasses, posing in front of a “Chemical” sign, she might be about to rob the bank. The book’s final third sets aside the personal, messy life and its protagonist. She is now in awe of architecture: buildings, bridges, and the grid. She stacks her pictures, aligning them in rows with vertical and horizontal bands of tape, and arrives at her own structure, builds her own city from page to page. She reflects the order and disorder of what Rem Koolhaas has called “delirious New York.” She photographs parades, construction sites, Wall Street, trash cans, a man sleeping in a doorway, and even art (Dubuffet’s 1972 sculpture Group of Four Trees and a mural reproducing Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte). She ends, appropriately enough, on Park Avenue, in the MetLife Building– formerly the Pan Am Building, a monument of International Style that Walter Gropius helped design. While there are any number of works by Genzken that occupy a central position in her overall body of work, there is one that has come to be seen as a simultaneously personal and artistic catalyst: I Love New York, Crazy City.