In Claire Bishop’s book, Radical Museology , the New York-based art historian argued that the global market climate of the last two decades has given rise to a new type of art museum, one that functions primarily as “a populist temple of leisure and entertainment” rather than as a space for research or education. She offered an antidote to the scourge of corporate “starchitecture”, suggesting that institutions with historical collections have become the most fertile testing grounds for what she terms “multi-temporal contemporaneity”, a fancy way of considering the cultural and historical context of new work through inclusive, relativistic curation. Museums took notice immediately, and today, the ripple effect of her theoretical findings is evidenced not only in state-sponsored white cubes, but the walls of local galleries and collectors' homes.

Bishop identified three museums that had successfully avoided the pitfalls of modern museology—Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid, and Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova (MSUM) in Ljubljana—noting that each of these examples pairs collected historical work with newer acquisitions to create content-based, forward-thinking exhibitions. In Bishop’s opinion, this “anti-presentist” approach not only helps repair viewer relationships with institutions, but restores humanist values in the public sphere.

This technique is applicable to the modern collector, too. Two pieces paired in conversation enrich, deepen, and engage each other in space, elegantly cracking open each other’s worlds. Here are 5 unexpected pairings between historically significant and new, fresh works, available now through Artspace.

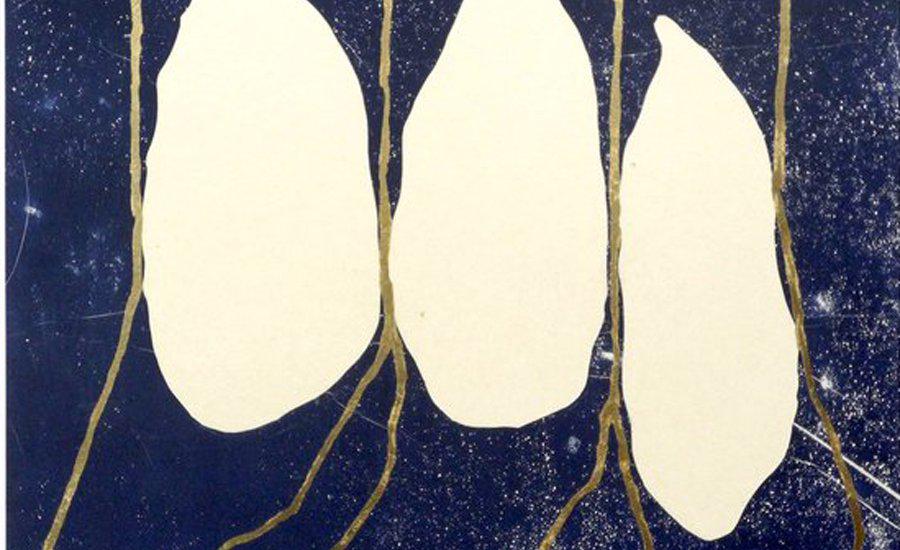

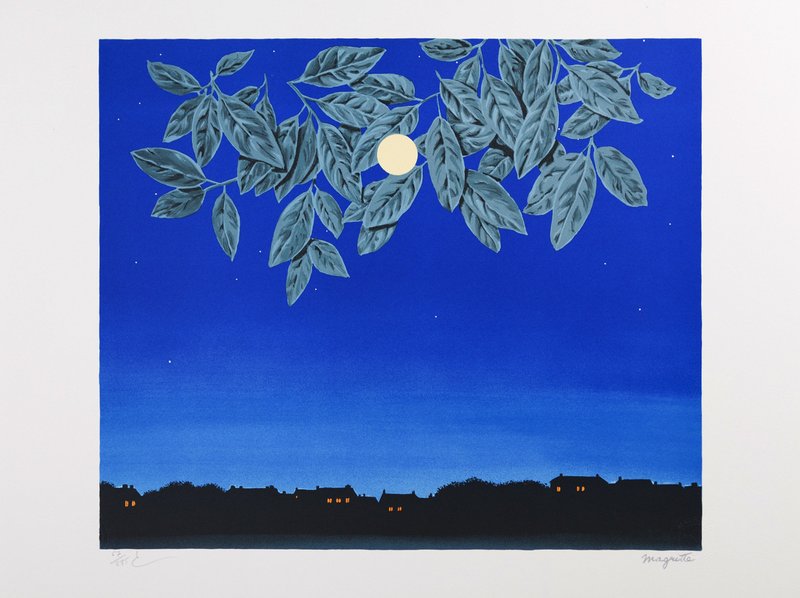

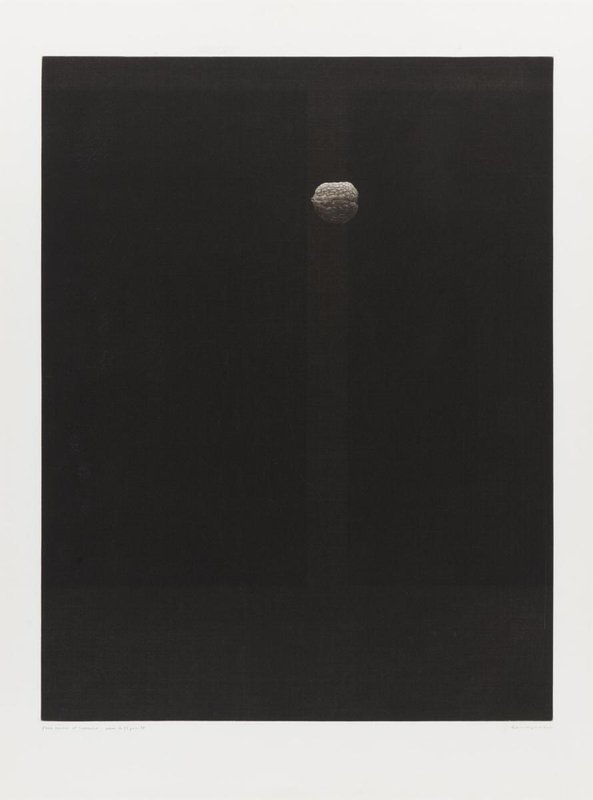

Rene Magritte , La Page Blanc, 1965 and Dominique Labauvie , Pleiades , 2019

Rhapsody in blue, but make it calming—these plangent reveries interact beautifully with one another in situ. Aside from the self-evident color palette synchronicity, each piece balances a calming tonal landscape with that signature destabilizing " what the hell ?" quality Magritte more or less patented in his Surrealist hey-day. Labauvie's intaglio static and creeping golden lines lend a contemporary version of that tell-tale tension to streamlined abstraction; one might even argue that Magritte's re-constitution of figurative signifiers is a form of abstraction unto itself. La Page Blanc and Pleiades both center organic orbs of blankness in deep, blue expanses, compositional modalities that magnetically draw the eye.

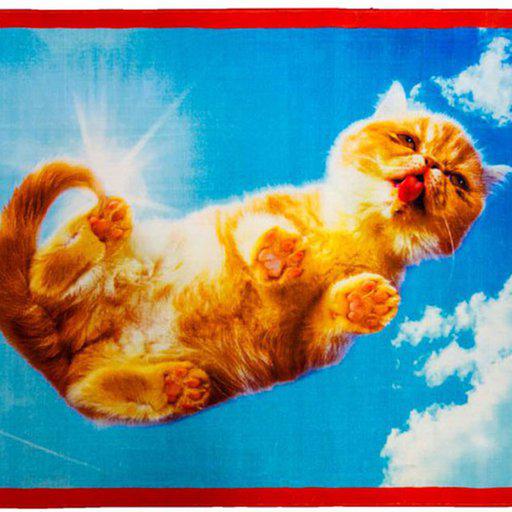

Ralf Peters , Tankstelle Sud , 2005 and Yozo Hamaguchi , Walnut , 1979

Are you afraid of the dark? These two pieces speak to the psychic murkiness of the urban-natural dichotomy. German conceptual photographer Peters specializes in capturing the otherworldly aspects of transitional, mundane spaces like gas stations, at once deeply impersonal and archly felt. It's little wonder that the German language has upwards of thirty different words to describe loneliness, a type of cultural specificity Japan also shares; Hamaguchi's Walnut speaks to carnal longing and isolation with an urgency atypical of most still-lives. Both pieces burn more slowly than most viewers might expect of photography, adding to the layered, emotional resonance of each print. The compositional dialogue between the pieces—dark, deft, and expert in terms of negative space deployment—is especially savory.

Walnut

, 1979, Mezzotint, 29.73" x 22.25", $7200, available now at Artspace

Walnut

, 1979, Mezzotint, 29.73" x 22.25", $7200, available now at Artspace

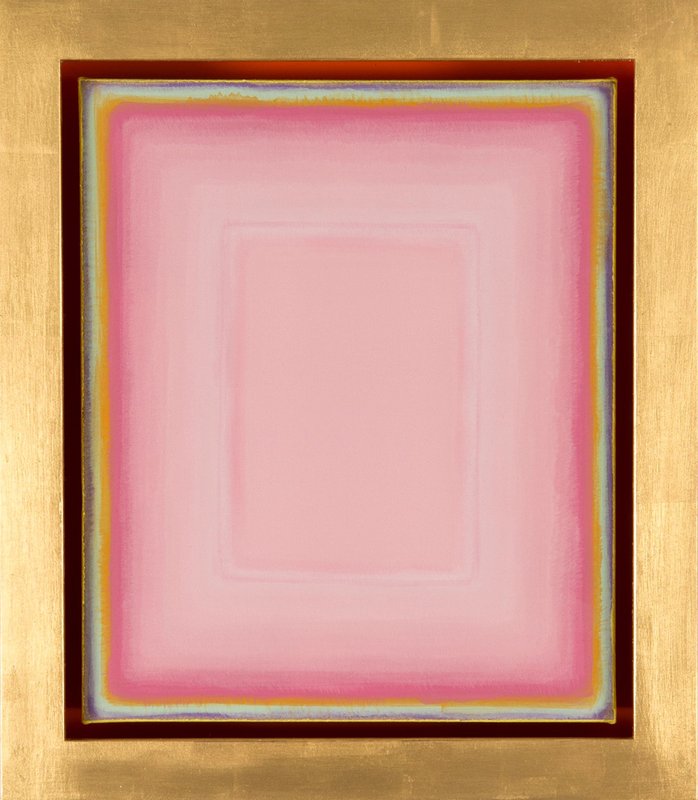

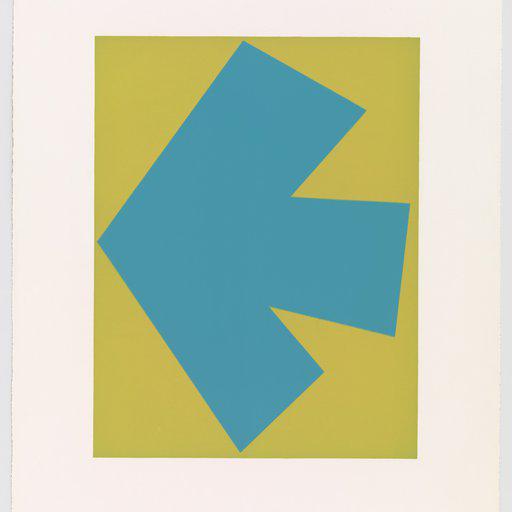

Tomislav Nikolic , To hear you now, to see you now, I must look outside myself , 2017 and Robert Motherwell , Untitled, Octavio Paz Suit e, 1987

There's little more satisfying than pairing color with black and white, and these two selections do one better; they're essentially compositional inverses of one another, as Nikolic's abstract color study gathers speed in the margins, whereas Motherwell's gestural kanji-inspired exclamation feels more centrally weighted. Despite their differences, the affectual and spatial reverberations of these two pieces both function expressionistically, and even Nikolic's piece has a direct correlation to the Color Field artists of the '50s and '60s - Motherwell's era.

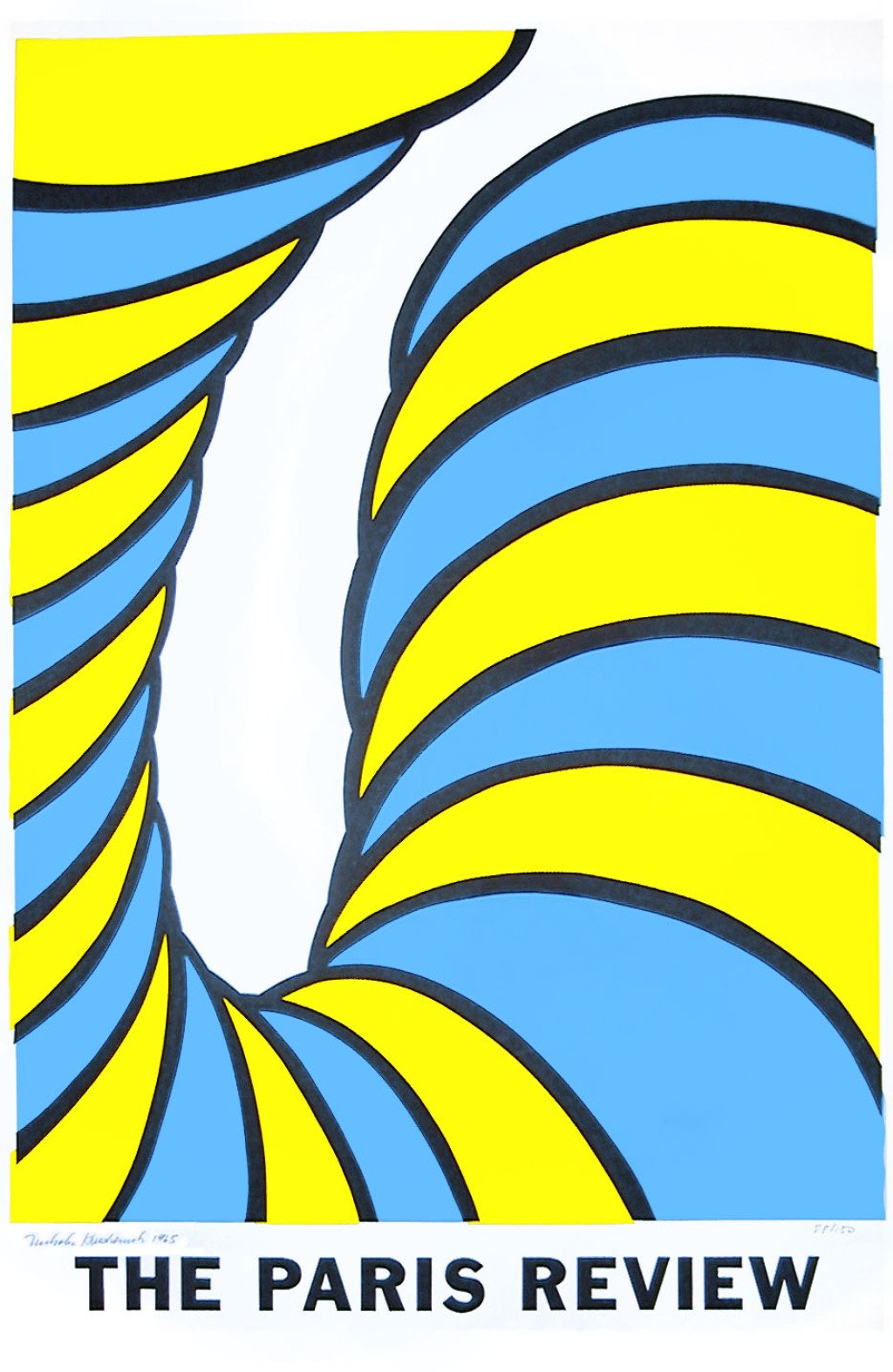

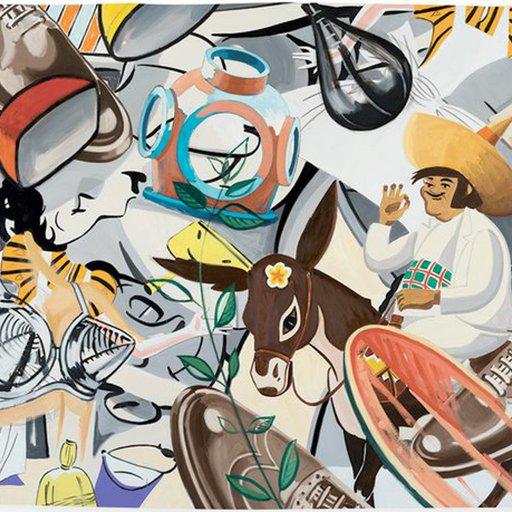

Nicholas Krushenick , Untitled , 1965 and Marta Minujin , All the Lovely People , 2010

Geometry becomes an uncontrollable force in this entropic Pop pairing, as there's nothing more dynamic than a veritable festival of stripes. Loud, proud, and bound to garner attention, these two pieces bandy to each other with befitting effervescence, electric, wild, and multitudinous in equal measure. Despite their graphic sensibilities, the most exciting aspect of these works has to be their distinct but parallel relationships with figuration, more explicit in Minujin's hodge-podge of bipedal forms, but equally seductive in Krushenick's iteration, swelling and bending with a truly human want.

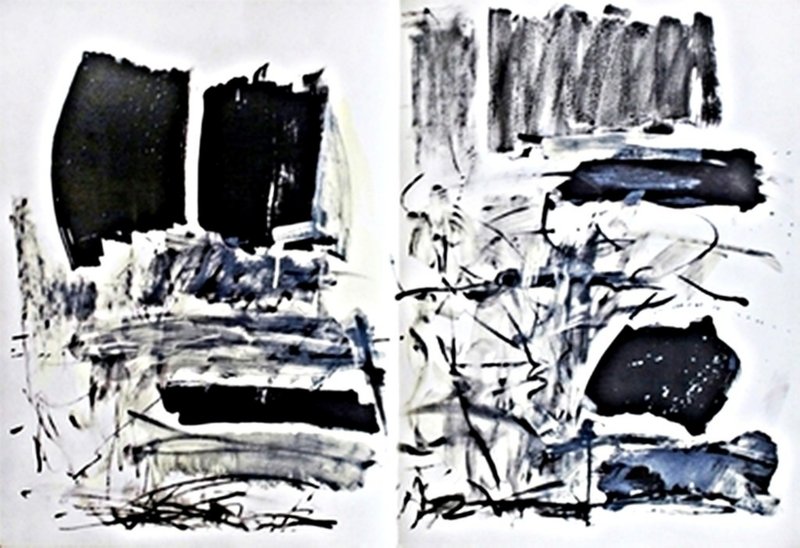

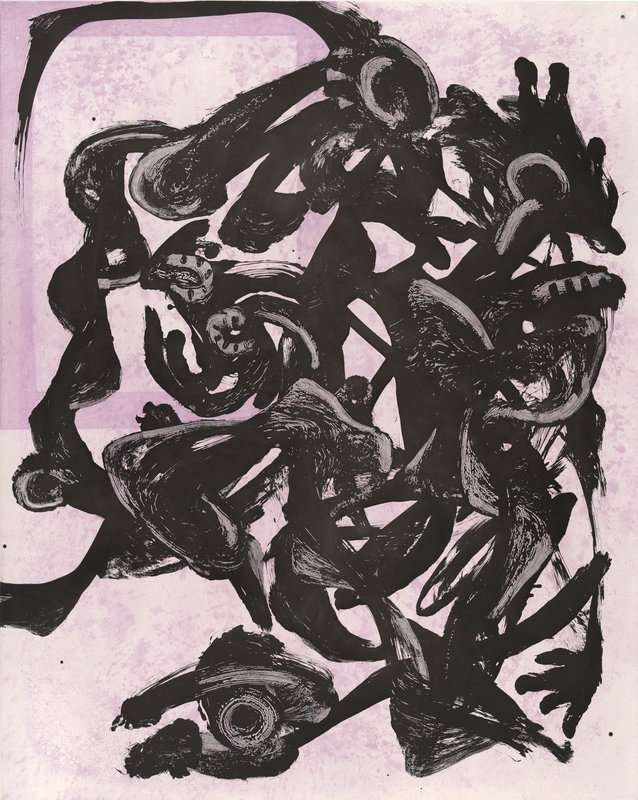

Joan Mitchell , Untitled from Carnegie Museum of Art Portfolio , 1972 and Charline Von Heyl , Nightpack (The Lost Weekend) , 2014

Across the decades, these two painters speak to each other’s intuitive, furious deployment of negative space with unparalleled flair. Each piece is its own testament to gesture as a means of emotional communication and expository world-building, making environments out of the 2-dimensional canvas space. Mitchell, a legend and tastemaker long ensconced in a painterly canon, sets scribbly pace mirrored by Von Heyl's slower, exploratory flirtations with the planar edge; an un-tamed ferocity lives within both sets of brushwork. This pairing represents an opportunity to see two important, chronically underrated female painters box with one another in real life, a truly exciting experience to behold.

Untitled from Carnegie Museum of Art Portfolio,

1972, folded lithograph, 15" x 22", edition of 1000, $1000, available now on Artpsace

Untitled from Carnegie Museum of Art Portfolio,

1972, folded lithograph, 15" x 22", edition of 1000, $1000, available now on Artpsace

Nightpack

(Gothic)

, 2014, aquatint, 52" x 42", edition of 10, $8500, available on Artspace

Nightpack

(Gothic)

, 2014, aquatint, 52" x 42", edition of 10, $8500, available on Artspace

RELATED ARTICLES

Why The Upper East Side Is the Best Place to See Art in New York

Get What You Want: How to Use Artspace's Free Advisory Services