Tax Season is here! Now before you freak out and run for the hills, take a deep breath. We're here for you.

Taxes are complicated––and for artists, well, they are especially complicated. But fear not! We've created an outline that should help clear up some of the more... abstract elements of this delightful yearly activity.

When it comes to transactions involving art, the IRS draws a distinction between whether you define your practice as a "hobby," or a "business." Before you spiral into an existential conundrum, trying to determine whether your practice is led by sheer passion or a desire to make piles of money (or more likely, a desire to feed yourself), let me explain.

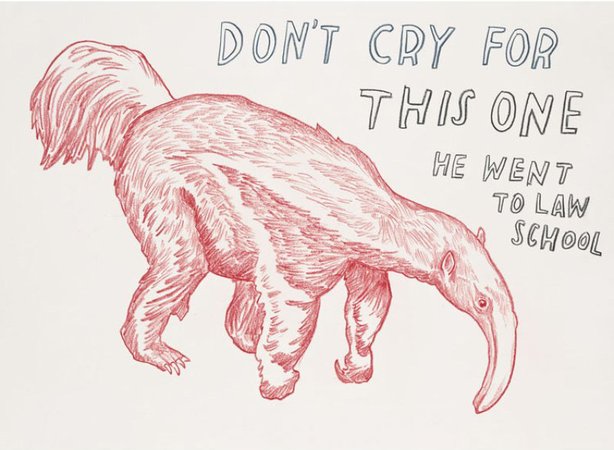

As you might have guessed, a business is for profit, whereas a hobby is not for profit. To put it simply, if your practice is for profit, you can deduct business expenses, and if your practice is not for profit, you cannot qualify your losses to offset another income. On their website, the IRS outlines some of the qualifiers and limitations that distinguish a business from a non-business. By their stipulations, an activity qualifies as a business if "it is carried on with the reasonable expectation of earning a profit." Some questions that might help you determine this (prepare yourself, some of these are potentially difficult to answer): Do you put time and effort into your art-making practice with the intention of selling the works? Do you rely on this income to eat and pay rent? If you lose money doing this activity, was it within or beyond your control? Have you made profits in the past? Have you changed your practice in order to improve profitability? Do you expect to see profits in the future? Here's this, as some comedic relief, (or to make you question your life choices) :

Dave Eggers, Untitled, (Don't Cry For This One, He Went to Law School), 2015, Available on Artspace

Dave Eggers, Untitled, (Don't Cry For This One, He Went to Law School), 2015, Available on Artspace

Ultimately, though, it comes down to your history. The IRS qualifies an activity carried out for profit based on whether you have made a profit in at least three of the past five tax years, (and at least two of the past seven years for activities that consist primarily of breeding, showing, training or racing horses, which is just a fun fact that you probably(?) don't need to know).

We asked a specialist at TurboTax how one would go about filing taxes as an "independent working artist," and here's what they had to say: "If you are an independent working artist, you are considered to be in business as a sole proprietor. The sale would be reported as General Income in your business income unless the gallery gave you a 1099-MISC. You would be able to deduct the materials and supplies that you purchased to create your art, and any other ordinary and necessary business expenses, such as advertising, business cards, etc. You may have vehicle expenses if you drove to galleries to exhibit your work. You may have a home office deduction if you have a studio in your home."

So yes, even though your practice may consist of you huddled in a drafty basement somewhere, sculpting chewed bubblegum into the shape of a giraffe; which, by the way, is pretty much the exact opposite of what comes up when you google image search "business"; it's likely that if you are selling your work, you are in fact, in the eyes of the government, a business. And you're not alone either––approximately 1/3 of the population is in the same situation. On paper it might seem weird, but at the end of the day, declaring yourself a "brand" is just a way of adapting to a changing job market that's still governed by an archaic system.

---

So, until freelancers band together and form a union, here are some simple proactive things you can do to help you prepare for filing your taxes.

1. KEEP YOUR RECEIPTS

Taxpayers can deduct "ordinary and necessary expenses for conducting a trade or business." These expenses are specific to trade; so rejoice in knowing that you can write off all of those expensive materials!

Sure, your studio may look like it's been ransacked by elves. Things are bound to get messy in your creative zone, and that's ok. But one thing you should keep as organized as possible are your receipts. Anything you spend on materials, studio space, studio utilities, etc. can be written off as a business expense. So keep track of it!

As someone who used to keep all of their receipts in a shoebox under their desk and then scramble around when tax season came; I know what it's like. But there are some very small things you can do to make this process a lot less painful. You don't have to have an elaborate filing system––just keep a few manila folders for the expenses that pertain to your practice. You'll thank yourself later.

According to Quickbooks.com, here are the types of expenses that you can deduct as a self-employed professional. So if you really want to make your life easier come tax season, set aside seperate reciept folders for each of the following categories that pertain to you:

- Advertising (business cards, website, etc.)

- Transportation (car or public transportation expenses that directly relate to your practice)

- Home Office (If your studio is in your apartment, look up how to calculate how much of your monthly rent you can deduct)

- Rent (your studio, if it's not in your home)

- Utilities (related to your studio or home office)

- Meals (you can include meals that you paid for while traveling to do an exhibition or artist talk, for example, as well as meals you have that are business related)

- Supplies (this is a big one: all your art materials)

- Travel (if you traveled to do a show, attend an art fair, speak at a school, etc., keep track of how much you spend on flights, accommodations, taxis, rental cars, etc.)

- Depreciation and Section 179 (you might be able to write off assets like computers, printers, and tools, but you need to fill out an extra form—Form 4562)

- Business Insurance (you probably don't have this, but if you do, you can write it off)

- Contract Labor (fees paid to fabricators, web developers, studio assistants, etc.)

- Interest (you can actually write off the interest you paid on your credit cards on studio-related expenses!)

- Repairs and Maintenance (to your studio or equipment)

2. CALCULATE DEDUCTIONS TO YIELD A GROSS INCOME

So you kept all of those receipts, now what?

Make an excel document of each of your write-off categories, and file accordingly. It's easier if you do it periodically as opposed to all at once. Designate a time at the end of the month to round up all of your applicable monthly expenses.

2. SET MONEY ASIDE

Because the majority of your income is untaxed, you are going to want to set aside a percentage of your gross income so that you're not slammed all at once when April rolls around. How much money depends on where you live, so look up what percentage of your income you'll owe. Be prepared to set aside up to a third of your income for taxes.

4. KNOW YOUR FORMS

Always know whether your gallery has claimed a sale as income. If they have, make sure they send you a 1099, and file those as seperately from your 1040 Schedule C.

If you sold a work on your own, you should, technically claim it as income (though most people don't, since the government doesn't really have any way of knowing about the sale.) If you do report sales income, use a 1040 Schedule C to report all sales revenues and expenses that pertain to your art making practice. All of the money you earned from selling your art goes on line 1. All of money you spent to make that work goes on line 4 (this is where your receipts come in handy). This will determine your gross income, which is what is taxed.

If all of the above information made you break out into a cold sweat; don't worry. There are some great freelance-specific resources out there to help you get through this dreaded part of the year.

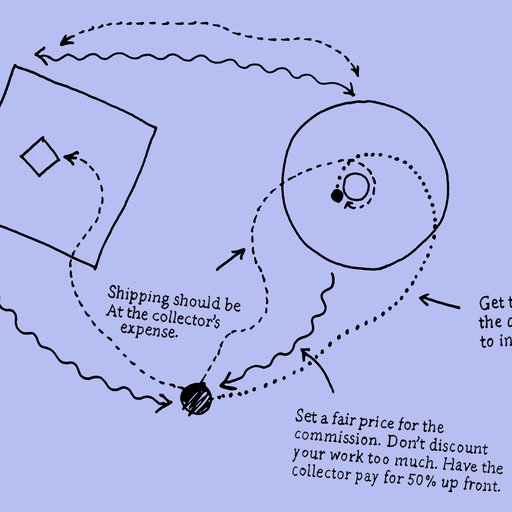

I spoke with the founder of Brass Taxes, Rus Garofalo, about how to estimate what you owe and alleviate stress. Says Garofalo, the root of the difficulty of filing taxes as a creative is a fluctuation in income, along with chance factors such as galleries not paying on time or artists not knowing what constitutes as a write-off. Because the stipulations of the IRS do not pertain to artists in a clear way (in a lot of ways it feels like trying to fit a square block into a circular hole), talking to someone can help you come up with estimates for how much you will owe, based on your past and potential future earnings, keeping in mind that your earnings are likely to fluctuate. Ultimately it helps to know that you're not alone, and aren't just taking a shot in the dark.

The main thing is, don't freak out. Tax season might actually be the only time when spending more money than you make on your studio practice is kind of a good thing.