In the moment, political art can feel transformative at its best, and at its worst, as Alain de Botton states , like "shouting forlornly in the wind." Works that question authority and challenge the status quo flourish during the most tumultuous of times, but what comes afterward? Below are four movements, selected from Phaidon's Art in Time , that found artists responding to the aftermath of troubled political times. Some made challenging work in spite of the rigid parameters set by their former authoritarian governments, while others used art as a way to assess the wounds left by their government's recent fascist past. Take a look and read their histories carefully—their tactics may offer some inspiration.

CHINESE WOODBLOCK MOVEMENT

Jiang Feng, Japanese Invasion of Shenyang, 1931

Jiang Feng, Japanese Invasion of Shenyang, 1931

The Chinese modern woodblock print movement flourished in the 1930s in a cultural climate in which intellectuals and artists were attempting to communicate social and political critique in China through visual means. Led by the left-wing writer and critical essayist Lu Xun , who had studied in Japan, the movement took off after Lu invited a number of art students to apprentice under Japanese printmaker Uchiyama Kakechi in 1931, following an initial exhibition of woodblock prints in Hangzhou in 1929. It gained momentum as a result of artists’ concerns with pressing social issues that were facing China as it struggled to modernize, along with the military threats from Japan that threw the country into full-scale war by 1937.

The visual impact of translated and illustrated publications from Russia and Germany fed into the Chinese Woodblock Movement , which shows clear links to German Expressionism and European engravings. Artists such as Käthe Kollwitz , Clément Moreau and Frans Masereel were highly influential on the movement for their succinct visual language in the woodcut form and their ability to portray clear messages about social injustice, abuse by exploitative landlords, conditions of severe poverty, and political unrest. The development of an urban cosmopolitan culture of literary and cultural journals was also a key factor in the Woodblock Movement due to the kinds of designs and illustrations published that exposed a range of foreign styles to China.

Li Hua, Roar, China!, 1935

Li Hua, Roar, China!, 1935

Roar, China!, by Li Hua , is the most iconic of the Chinese woodcut images of the 1930s. As a powerfully intense visual personification of China’s sense of enslavement as an emergent nation, it shows the clear influence of German Expressionism in the extenuated lines of the feet and hands and the emotionality of the image. The Belgian artist Frans Masereel ’s use of zigzag line and geometric composition is also visible in such works as Japanese Invasion of Shenyang by Jiang Feng . Other artists, such as Gu Yuan , one of the great masters of the medium whose style was more nuanced and narrative-based, showed more realist tendencies. Later woodblock prints of the 1940s adapted earlier works to merge with aspects of the New Year printmaking ( nianhua ) tradition.

The Woodblock print movement strongly influenced the style of propaganda posters made in the first two years of the Cultural Revolution, a period of fundamentalist Maoism when some of China’s most distinct revolutionary imagery was produced.

JIKKEN KōBō

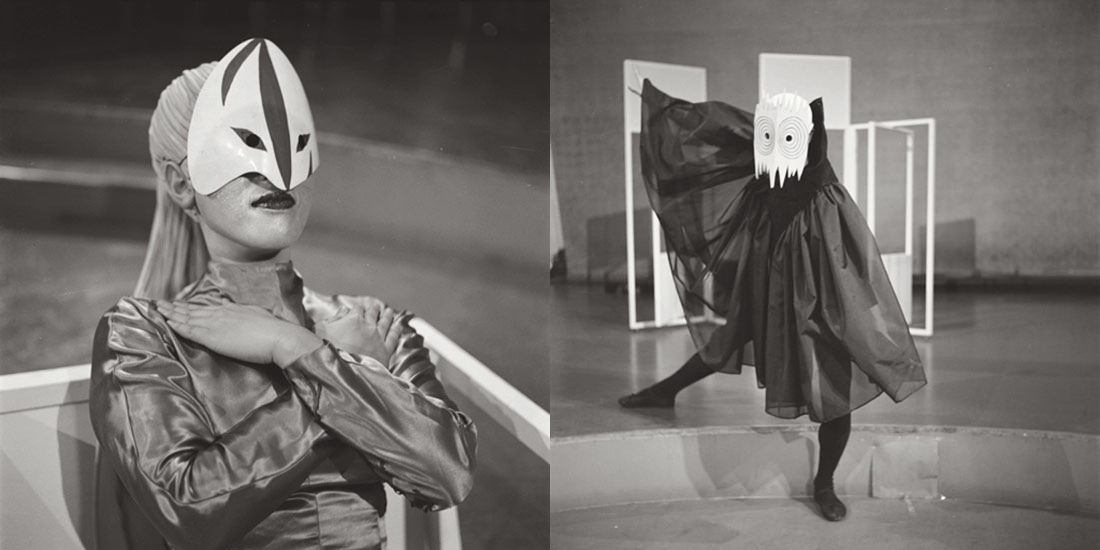

Jikken Kōbō with Kawaji Akira and Matsuo Akemi, The Future Eve, 1955

Named by art critic and poet Takiguchi Shōzō in 1951, Jikken Kōbō (meaning “Experimental Workshop”) was an eclectic collaborative that included artists, musicians, lighting designers, and poets. Aligned closely with the ideals of Takiguchi, who served as a mentor to the group, Jikken Kōbō artists used the concept of experimentation to question and critique conventions of art in Japan. These included the staging of exhibitions in galleries and museums, and the tendency to adopt modern Western styles formulaically as signifiers of modernism without understanding their conceptual basis. Experiment was seen as a means to artistic freedom—a poignant goal in the aftermath of Japan’s wartime authoritarian regime.

In the spring of 1950, an art collective named Toridan (Trident) and a group of musicians who had met as members of a choir in 1946 began a series of discussions and informal concerts that grew into Jikken Kōbō . Their first collaboration, the ballet The Joy of Life , staged in conjunction with a 1951 Picasso exhibition, set the tone for their rigorous experimentation, bringing art out of the exhibition hall and into direct conversation with music, dance, and poetry. The Joy of Life set a precedent for connecting with international art and music practices, and Jikken Kōbō not only drew inspiration from international modern art movements, including Expressionism and Constructivism and Surrealism but also introduced the music of Olivier Messiaen, Béla Bartók and Leonoard Berstein to Japanese audiences.

Jikken Kōbō and Takechi Tetsuji, Pierrot Lunaire (tsuki ni tsukareta piero), 1955.

In 1953, Jikken Kōbō began to work with the autoslide projector, recently developed by Sony. This projector enabled images to be synchronized with magnetic tape recordings, creating a fully integrated experience of moving image, sound and spoken word distinct from and less expensive than 35mm film. In their ‘Fifth Presentation,’ Tales of an Unknown World and three other autoslide works were presented, each incorporating futuristic imagery and a variety of sounds from music to poetry to documentary narration, and purportedly including Japan’s first instance of musique concrete . The collaborative image-making of the autoslide works led to a series of interventions from 1953 to 1954 in the Asahi Picture News section of the major weekly magazine Asahi Graph . Each week the APN title page featured a photograph of a construction by a different member of Jikken Kōbō, with each successive image playing off the previous ones.

In spite of a fascination with science fiction, the group’s distrust of modern industrial production explains why Jikken Kōbō never incorporated into a Bauhaus -like artists’ production company, electing to remain independent and experimental until officially disbanding after 1957. Many of its members participated in experimental events at Sōgetsu Art Center and Osaka’s Expo ’70, and set the tone for rebellions against the art establishment that led to the development of anti-art by groups such as Tokyo Fluxus , Hi Red Center , and Neo-Dada in the 1960s.

LETTRISM

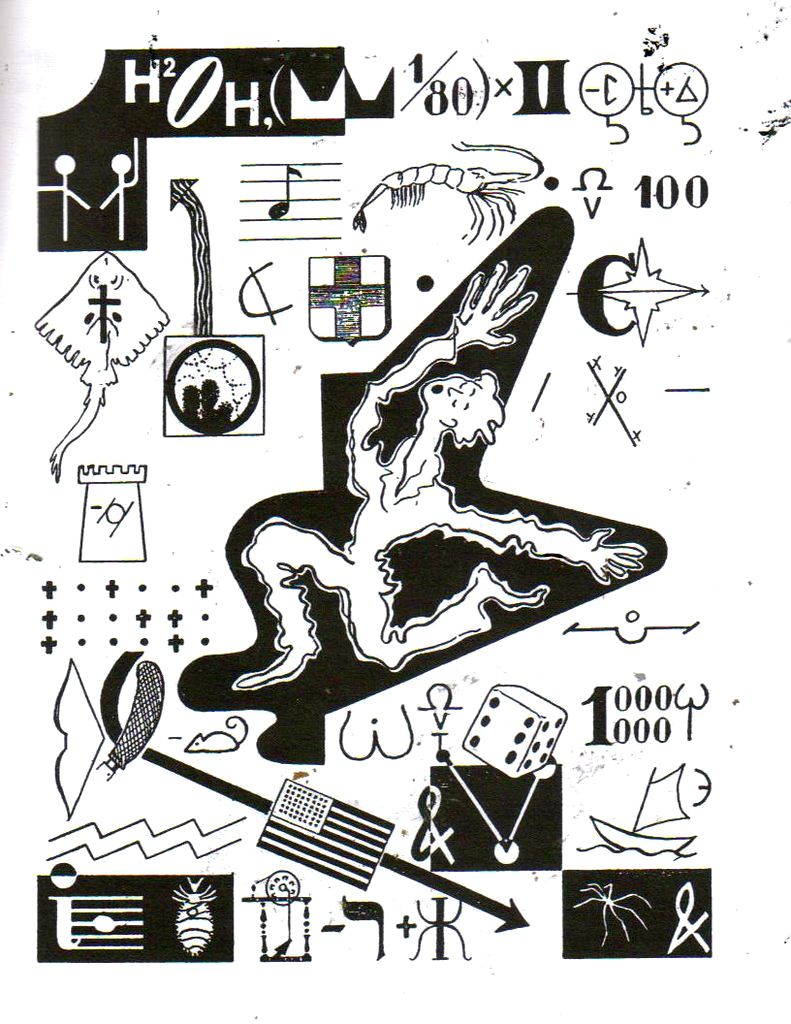

Gabriel Pomerande, from Saint Ghetto of the Loans, 1950

Gabriel Pomerande, from Saint Ghetto of the Loans, 1950

Between 1945 and 1972, the two most uncompromising avant-garde groups in Paris were Lettrism and the Situationist International (SI) . Their histories are intimately intertwined by their shared engagement with Surrealism and Marxism and their trenchant critique of all existing visual, linguistic, and political structures. The Historical Lettrism group was founded by the Romanian émigré Isidore Isou in the literary quarter of Saint-Germain-des-Prés before an ideological schism led to the emergence of the Lettrist International, a splinter group steered by Guy Ernest Debord . This group eventually consolidated with the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus , led by the Danish artist Asger Jorn , to form the SI.

The Historical Lettrists, among them Isou, Gabriel Pomerand , Gil J. Wolman , Maurice Lemaître and Fraçois Dufrêne , attacked the integrity of poetry, film and painting by reducing each medium to its most basic building block. To reconstruct life in the wake of World War II and revolt against the catastrophic complicity between culture and fascism, poetry was decomposed to letters, signs, phonemes and human breath (as in Isidore Isou’s Réseau centré M67 ); film was trimmed to celluloid support and the contrast between the projection of white light and the darkened space of the cinema; and painting was diluted to cryptic symbols and elementary graphic inscriptions. Debord, who joined the Lettrists after meeting Isou at the scandalous screening of Traité de bave et d’éternité at the Cannes Film Festival in April 1951, instigated a putsch against the older radical in October 1952.

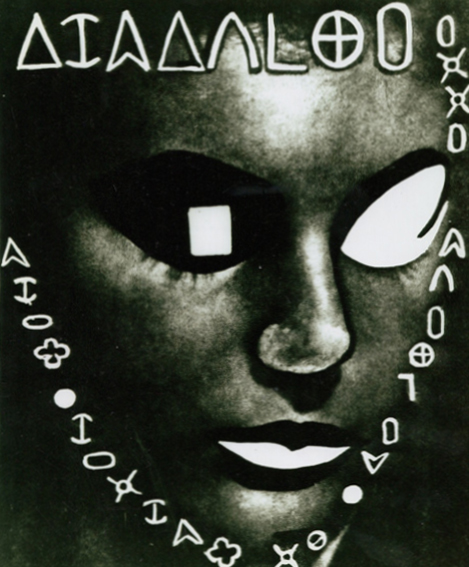

Maurice Lemaître, Scoundrels IV, 1952

Maurice Lemaître, Scoundrels IV, 1952

Both the Lettrist International and the SI were born out of a desire for greater political militancy and drew inspiration from the writings of Marxist sociologist Henri Lefebvre, who argued for a ‘critique of everyday life.’ In the face of intensifying economic modernization, the chief protagonists of the SI sought techniques to subvert the entwinement of social life with market forces. Debord and Jorn performed dérives (‘transient passage through various ambiences’) in Copenhagen and Paris, reordering the cities’ capitalist logic according to chance encounters and the flow of unconscious emotions and desires. The visualization of this “psychogeography,” frequently through the disorderly combination of various images, texts, and events from different eras, provoked a destabilizing détournement , or misappropriation.

Though Debord decreed that artistic practice and political struggle could not be separated, in 1962 an internal rift divided between activists and artists. In the years leading up to the uprisings of May 1968, the activist wing of the SI published books and pamphlets, including Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle , which became seminal for the student movement. It is fitting that the SI slogan, “Beauty is in the Street,” graced revolutionary street posters throughout Paris during France’s biggest general strike of the twentieth century.

VIENNESE ACTIONISM

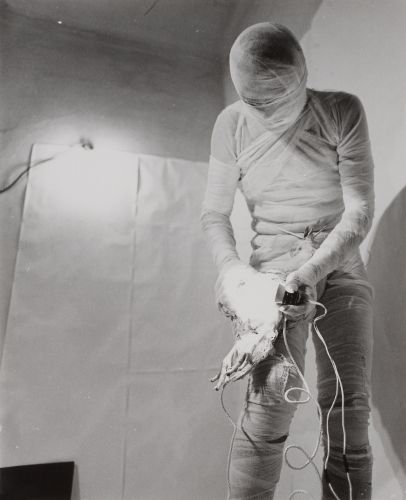

Günter Brus, Vienna Walk, 1965

Günter Brus, Vienna Walk, 1965

Although often grouped with Happenings and Fluxus , the Viennese Actionists belonged quite distinctly to their own socio-historical framework. It was in the oppressive milieu of post-War Austria, a country coming to terms with its home-grown version of fascism, annexation by the Third Reich and enforced democratization through the Allied Occupation, that Günter Brus , Otto Mühl , Hermann Nitsch and Rudolf Schwarzkogler came of age. Between 1962 and 1968 they performed some of the most shockingly violent and transgressive “actions” of the 1960s. By sexualizing and desecrating their bodies, incorporating blood, food, semen, urine and excrement into their practices, and alluding to religious iconography, the Actionists aimed to subvert social taboos and trigger individual and collective catharsis in a wounded public.

Paradoxically, while they confronted spectators with the disciplinary social norms that shaped society, the Actionists created their own power structures. This is evident in their violation of traditional easel painting, a crucial aspect of Actionism visible in Nitsch’s

Station of the Cross

and Mühl’s

Food Test

. Nitsch’s drenching of canvas with paint and animal blood and Mühl’s fetishized amalgamation of female bodies and foodstuffs within pierced canvases were in direct conversation with

Jackson Pollock

’s gestural abstraction while specifically reclaiming the pre-war psychoanalytical theories of Sigmund Freud, Willhelm Reich and Carl Jung.

Otto Mühl, Food Test, 1966

Otto Mühl, Food Test, 1966

For Schwarzkogler, reliving psychic pain meant simulating bodily abuse and healing, mostly using the artist

Heinz Cibulka

as a protagonist. The black-and-white images comprising the

2

nd

Action

and

3

rd

Action

depict an anonymous convalescent—here with bandaged head and taped groin that oozes blood, there his temple being injected with a syringe. Taking this disruptive body into the public sphere in

Vienna Walk

, Brus painted a black scar down the middle of his whitened head, hair and suit and paraded around the city before being stopped and fined by the police.

Richard Schwarzkogler, 3rd Action, 1965

Richard Schwarzkogler, 3rd Action, 1965

Brus and others revealed that the authority of the state extended to every aspect of civic life at the notorious “Art and Revolution” event at the University of Vienna on June 7, 1968, advertised as a discussion on the possibilities of art in a late capitalist society. In front of the assembled students, Brus slashed his chest and legs with a razor blade, urinated in a glass, defecated on the floor, made himself vomit and masturbated while singing the Austrian national anthem. Sentenced to six months in jail, he fled to West Berlin. This massive public disturbance signaled the culmination of Actionism, though many subsequent artists continued to situate the degraded body at the juncture between public and private in order to expose the complex circuits of power that animate their interactions.