Pop culture and design loves to appropriate grossly stereotypical elements of percieved Native American cultures (do I really need to bring up Coachella?), learned from normalized racially insensitive media portrayals such as the "Piccaninny Tribe" in Disney's Peter Pan . Contemporary multi-disciplinary artist Merritt Johnson, a descendant of the Blackfoot and Kanienkehaka Tribes, writes that most people think of “beads and feathers” when they hear the term "Native American art." This pigeonholing, among being immensely generalized and demeaning, fails to the acknowledge unique individual expression between and within Native American communities. There are 567 federally recognized Native American nations in the United States. Amongst those tribes exists a great deal of diversity in culture, language, and elements of day-to-day life such as food preparation and dress. Conflating Native American cultures disregards this diversity, and effectually silences Native American voices.

This is what makes the Jimmie Durham controversy so complicated. In case you missed it: Durham has long been regarded as the central, or at least the most well-known figure of Native American Art. He has historically identified with Cherokee descent (along with a bizarre slew of celebrities including Johnny Depp, Cher, Miley Cyrus, and Johnny Cash), and this identity is a central aspect of his work. Durham's recent retrospective at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis has sparked a massive controversy, as multiple Cherokee artists and curators claim that Durham is not in fact recognized by any of the three Cherokee nations. In an article published on Indian Country Today , contributors write that "Durham continues to misrepresent Cherokee language, history, and culture. Throughout his career, he has misrepresented other’s tribes’ practices (giveaways, vision quests, Trickster Coyote, feasts of the dead) and said they are Cherokee. His fabrications insult not only us but also the other tribes whose cultures Durham has misappropriated."

The controversy is complex, as Durham was a fervent activist with the American Indian Movement in the '70s, and his work has always relied on themes of Native American identity and the destructive nature of colonization. In a recent New York Times article, Durham admits, “I am perfectly willing to be called Cherokee.... But I’m not a Cherokee artist or Indian artist, no more than Brancusi was a Romanian artist.” (Brancusi was born in Romania.) But it also sounds a whole lot like that time "Iron Eyes Cody," the actor in the infamous 1970s "Crying Indian: Keep America Beautiful" PSA video who earned a number of roles on the premise that he was Native American, was "outed" as second-generation Italian.

It's about time that Native American artists start getting recognition and support for their work, apart from the media representations by non-Native folks. Meet these eight groundbreaking artists of Native American descent, working in a variety of mediums, who are making moves to counter the stereotypes of Native American art and culture in contemporary society.

---

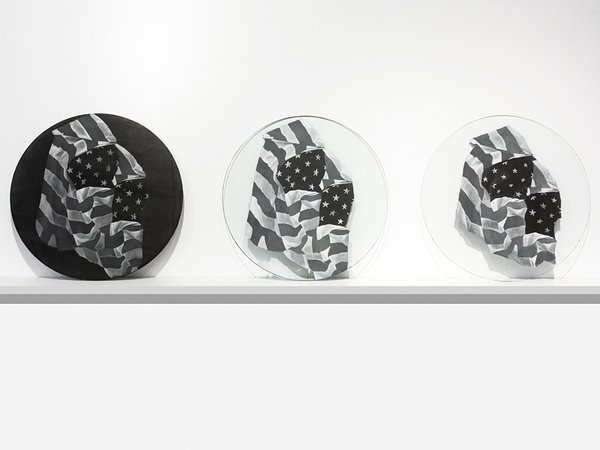

Nicholas Gallanin

"The American Dream is Alive and Well", 2012

"The American Dream is Alive and Well", 2012

Born in Sitka, a borough of Juneau, the capital of Alaska, Nicholas Gallanin is a conceptual artist and a musician of Tlingit and Unangax descent. Gallanin has a way of making artworks that mix completely contemporary-looking aesthetics with historical or traditional elements of his culture. For example, a series of prints use images of Native Americans overlaid with text, rendered in the style of Pop Art, with bright colors and Warhol-eque graphics. For his video Tsu Heidei Shugaxtutaan 1 , which won the 2008 ImagineNative Film Festival, he paired video footage of a break dancer and audio of a traditional Tlingit song. In another video, he paired traditional Tlingit dance with sparse electronic music. Gallanin often repurposes objects like handcuffs used to remove Indigenous children from their homes, and makes clear society's tendency to bury historical truths. He writes "culture is rooted in connection to land; like land, culture cannot be contained."

Wendy Red Star

"Fall" from the series "Four Seasons," 2006

"Fall" from the series "Four Seasons," 2006

Wendy Red Star, a Native American artist of the Apsáalooke (Crow) lineage, born in Billings, Montana in 1981, is known for her funny, surreal, but biting self-portrait photographs that poke fun at white American culture's tendency to misrepresent Native American history. Red Star's photography practice is her way of navigating her experience growing up on a Crow Indian Reservation, juxtaposed with her experience of mainstream contemporary society. Using materials like Target-brand Halloween costumes and inflatable animals, Red Star counters the stereotypical trope that all Native American people are "one with nature." In her Four Seasons Series , Red Star photographs herself dressed in traditional Apsáalooke clothing against four different richly saturated panoramic Western landscape backdrops (which she is careful to leave with creases and wrinkles to exemplify their artificiality), reminiscent of dioramas one might see at a history museum, populated with artificial, store-bought materials such as fake plants, cardboard cutouts of animals, and astroturf. Her photo series Home is Where My Tipi Sits features collections of photographs from the reservation she grew up on after she returned from UCLA, where she received her MFA. The photographs are grouped by category, and feature broken down cars, churches, and decrepit living structures covered in blankets that stand in opposition to the stereotyped romantic perception of Native American life.

Post-Commodity

"Coyotaje", Installation, 2017, Image courtesy of the artists

"Coyotaje", Installation, 2017, Image courtesy of the artists

Postcommodity is an interdisciplinary activist/arts collective consisting of Native American artists Kade L. Twist, Raven Chacon, and Cristóbal Martínez. You may recognize Postcommodity from the collective’s contribution to the Whitney Biennial earlier this year: a dizzying four-channel video sped up and slowed down in conjunction with sound, tracing the fences that line the US-Mexico border. The installation, titled A Very Long Line , demonstrates the "dehumanizing and polarizing constructs of nationalism and globalization through which borders and trade policies have been fabricated.” In their artists's statement, the collective writes "Postcommodity’s art functions as a shared Indigenous lens... to engage the assaultive manifestations of the global market and its supporting institutions, public perceptions, beliefs, and individual actions that comprise the ever-expanding, multinational, multiracial and multiethnic colonizing force that is defining the 21st Century through ever increasing velocities and complex forms of violence." Borders seem to be a recurring theme; Repellent Fence (2015), an ephemeral land-art installation comprised of 26 enlarged replicas of an ineffective bird-repellent balloon, hovered 50 feet above a two-mile long stretch of land connecting the US and Mexico. The group hopes to incite a constructive conversation about social, political, and economic forces that are destroying communities globally.

Duane Slick

"Accessing the Moment of De-Materiality," Triptych, Acrylic on Glass, 2010

"Accessing the Moment of De-Materiality," Triptych, Acrylic on Glass, 2010

Duane Slick is a Native American painter and storyteller of the Meswaki Nation. His photo-realist paintings on glass and linen have a dream-like, spiritual quality, using subtle shadows, light studies, and layering. His series Disagreeable Coyotes (2015-2016) consists of nine acrylic-on-panel minimal paintings of coyote heads, layered in bright reds, blues, and yellows, reminiscent of a full color 3D film watched without the glasses. Of the paintings, Slick writes, “In narrative traditions, to tell the story of tragedy one must always begin by telling the ending first. I once believed that the weight of such expectations functioned as a cultural given for the artist of Native American descent. Its rules stated that we cry for a vision and place ourselves in a single grand narrative of history and representation... but the laughter of Coyote saturated and filled our daily lives. It echoed through the lecture halls of histories and it was so powerful and it was so distracting that I forgot my place in linear time and now I work from an untraceable present.” Slick is represented by Albert Merola Gallery in Provincetown, and his work appears in a number of collections across the United States including the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City. He teaches printmaking and painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, and has taught at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Merritt Johnson

"Open Container", Sculpture, 2014-2016

"Open Container", Sculpture, 2014-2016

Merritt Johnson is a multi-disciplinary artist of Blackfoot, Kanienkehaka, Irish and Swedish descent. She works in sculpture, painting, and video, but has a special affinity for performance art, for the way it allows her to embody the past, present, and future all at once. Her work speaks to the relationship between Native American history and "American" history. She comments on the boundaries that humans create (borders, fences, state lines), as juxtaposed with the natural boundaries of nature (airflow, waterflow). In her performance Clouds Live Where , viewers watch from above as Johnson delineates space using tape, wood barricades, and fabric. The artist attempts to navigate this barricaded space, transporting water back and forth from clouds to land. Says Johnson “tongues and knives cut the intersections of land, culture, sex, and body, so I weave together seen and unseen; looking with closed eyes open, breathing in and out.” Another recurring theme in her work is camouflage, illuminating the complete disregard of indigenous people as part of American society. Her work plays with the unseen, exploring its “precarious possibility (of) endless creation and destruction. She is interested in the ways that indigenous and non-indigenous people's interpretations of her work differ, specifically with regards to the treatment of land and nature: on the one hand respected and imbued with spiritual qualities and on the other looked at as a resource. Without judgement, she says, humans can feel that all things are ultimately intertwined.

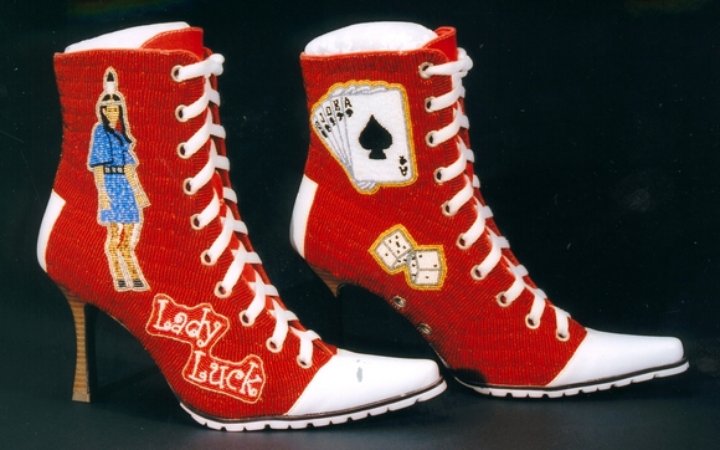

Teri Greeves

"Deer Woman as Lady Luck," Beaded Tennis Shoes, 2004

"Deer Woman as Lady Luck," Beaded Tennis Shoes, 2004

Teri Greeves (b. 1970), originally from the Wind River reservation in Wyoming, is known primarily for her use of the traditional Kiowa art of beading, which she learned from her grandmother. She writes that her grandmother expressed herself through beadwork, and despite working menial jobs as a dishwasher and a cleaner, she was always primarily an artist. Greeves has been working with beads since she was 8 years old, and for her, being an artist is about giving a voice to her ancestors before her. She writes, "I am compelled to do it... I have no choice in the matter. I must express myself and my experience as a 21st Century Kiowa and I do it, like all those unknown artists before me, through beadwork... and though my medium may be considered 'craft' or 'traditional,' my stories are from the same source as the voice running through that first Kiowa beadworker’s needles. It is the voice of my grandmothers." Greeves merges her cultural history with contemporary objects, as in the case of her tennis shoes series (shown above). She blends traditional geometric traditional Kiowa styles with figurative elements of the Shoshone, while also commenting on the derivation of American modernist abstraction from traditional Native American designs. Her figures are adorned with both traditional and contemporary clothing items, as a commentary on being a Native American woman in the modern world. Her work appears in numerous public collections including the Brooklyn Museum, the Denver Art Museum, the National Museum of the American Indian, the New Mexico Museum of Art, the Heard Museum, and more.

Matika Wilbur

Photograph from Project 562: "Changing the Way We See Native America"

Photograph from Project 562: "Changing the Way We See Native America"

Matika Wilbur is a photographer and storyteller of the Tulalip and Swinomish Tribes. She has been traveling across the country for over 5 years, taking portrait photographs of Indian Tribes across the country to reclaim the Native American image, and to effectually change the way that Native Americans are represented. Wilbur has a background in fashion and commercial photography, and despite being very successful in her career, she knew in her heart that she had to use her voice to expose the diverse, unique individual personalities amidst America’s indigenous communities, who are too often either neglected or misrepresented. She began her portrait photo-series titled Project 562 in order to communicate the lives of neglected and/or misrepresented peoples. Her portraits capture a sense of intimacy and genuine raw emotion, likely because of Martika’s process. Her subjects choose where they want to be photographed, and Martika spends up to multiple days with them, bringing gifts and sharing songs and prayers. She seeks to bring the individual to life in her works, placing her photos side by side with text from the subject. She views herself as a “creator and messenger,” and her project is a form of re-education, offering a comprehensive visual curriculum of contemporary Native culture. She writes "while holding true to my heritage and tradition, I aim to empower contemporary visions. I believe that my work is the answered prayers of my ancestors, as I walk the path they fought to pave.” Wilbur has travelled to over 300 sovereign nations so far, and her photographs capture the vast diversity within and between indigenous communities.

Frank Buffalo Hyde

In-Appropriate #1, 2013

In-Appropriate #1, 2013

In his vibrant, richly saturated, satirical graphic realist paintings, artist Frank Buffalo Hyde (b. 1974) juxtaposes 21st century pop culture signifiers with symbols and themes from his Native American heritage. Born in Santa Fe and raised on his mother’s Onandaga reservation, Hyde seeks to dismantle stereotypes of Native American culture with his work. He takes imagery from pop culture, politics, films, television shows, etc. and overlaps the references to replicate what he refers to as “the collective unconsciousness of the 21st century. In his painting series “In-Appropriate,” Hyde paints satirical portraits of people wearing “jacked-up portrayal(s) of Native American imagery” that are at once funny and revolting. Hyde overtly defies the aesthetics of what people might think Native American art “should” look like, including subjects such as selfie-sticks, iPhones, cheerleaders and plates of buffalo wings. His narrative series I-Witness Culture explores life as a Native American in the digital age. Hyde’s work addresses contemporary America’s fear of the “other,” and the tendency to homogenize indigenous cultures to counter this fear (which ultimately materializes as racist mascots and costumes). Hyde’s work has been exhibited internationally, and he was artist-in-residence at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Make America Mexico Again: 10 Artworks About Immigration and the Border

9 Totally Badass Latina Artists in the Hammer's "Radical Women" Show