In the 30 years since Raymond Pettibon first rose to fame for his seemingly casually drawn yet impeccably composed comic-style drawings, his approach to art hasn't changed much—and critics have never ceased to applaud his attitude-suffused work. Pettibon makes it look easy. His ink-and-graphite works on paper combine text and striking images to produce statements about American culture that are humorous, anarchic, and disturbing at the same time. Quotations from the Bible get compared with images of Charles Manson in crude ways, baseball players with sweet swings accompany musings both banal and philosophical, surfers ride blissful curls of blue, politicians appear broken and corrupt, and the result is a body of work unlike any other in contemporary art. (Unless, say, Roy Lichtenstein had mined underground zines for his inspiration rather than the funny pages.) Here is a guide to the major themes in Pettibon’s oeuvre.

PUNK AT HEART

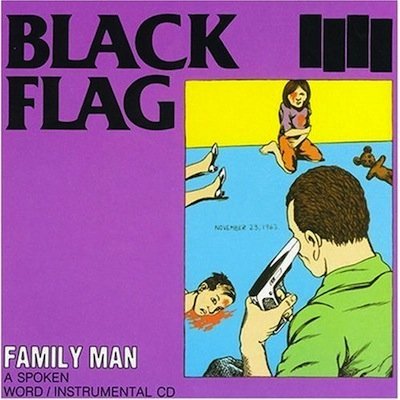

Pettibon's cover for Black Flag's Family Man (1984)

Pettibon's cover for Black Flag's Family Man (1984)

When Raymond Pettibon was still eking out a living as a high-school math teacher named Raymond Ginn in the late '70s, he got his big break—only he didn’t realize it at the time. Pettibon’s brother, Greg Ginn, was part of a then-unknown band called Panic. After one band member realized there was already another band named Panic, Pettibon suggested the name Black Flag, which, according to him, stood for anarchy—the opposite of a white flag. With Henry Rollins on vocals as a brutal force of sonic destruction, Black Flag ultimately went on to be one of the most influential punk bands ever, and Pettibon designed all but one of their album covers.

The covers of the Black Flag albums exemplify Pettibon’s aggressive style. For the cover of Family Man, Pettibon shows a father who appears to have shot his children and is getting ready to shoot himself. Like Pettibon’s drawings, the cover art is wry, satirical, and hand-drawn, emblematizing the “do-it-yourself” attitude that had become central to the punk scene. More recently, however, Pettibon has said that he doesn’t think he has quite as much to do with punk as critics have written.

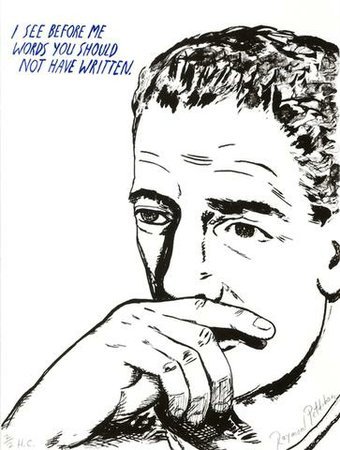

THE WRITTEN PICTURE Untitled (I see before me...) (2002)

Untitled (I see before me...) (2002)

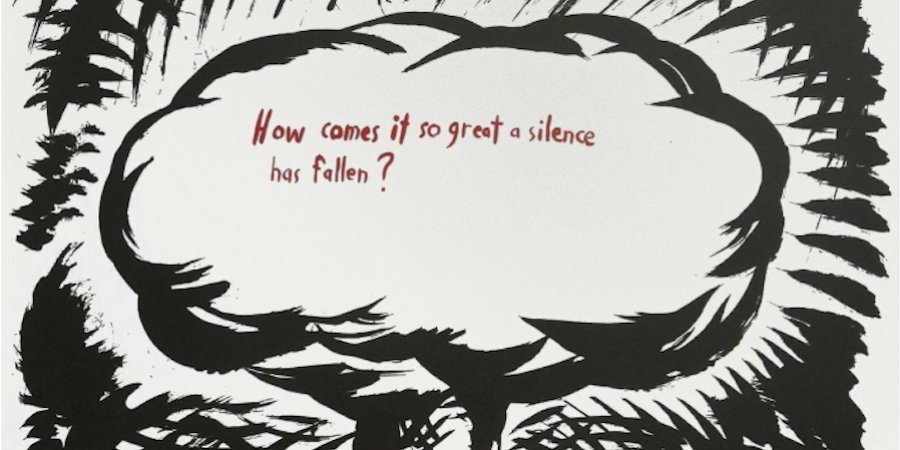

Pettibon’s last name itself displays his love of language. Pettibon adopted the surname when he became an artist to make a pun on the nickname “petit bon,” or “good little one.” His drawings similarly share this love of language, combining image and text in strangely poetic style that suggests what William Blake might have done had he gone into comic books. Like the images in Pettibon’s drawings, the text can vary greatly, even if it is always written in the same sans-serif font. Sometimes, the text can take up most of the drawing. Other times, there may be only a few words floating in the ether. The language is as slangy, idiosyncratic, and informally confessional as the drawings themselves.

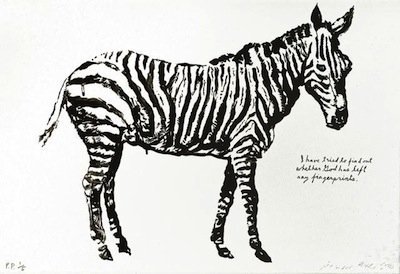

TAKE A LONGER LOOK Zebra (2000)

Zebra (2000)

Ask anyone who follows Pettibon on Twitter, and they’ll be well-versed with his arresting authorial voice (and may even, at one point or another, considered unfollowing him). His bitter tweets are often written in semi-gibberish, employing the letter “y” more frequently than strictly called for. They shake you awake, and the same goes for the unpolished pronouncements he puts in his art. But Pettibon insists that the language he uses, no matter how conversational, is meant to be difficult to digest. When asked about the phrases written in his drawings, Pettibon has said that his writing is meant to force people to look at them a longer period of time.

Pettibon’s drawings also quote from various sources, from the Old Testament to Henry David Thoreau to advertisements. When reading a Pettibon drawing, it’s impossible not to feel an eerie sense of familiarity with the quote, and that, too, providing a sense of recognition that lingers in the memory. Even when the quotation’s source is obvious, its relation to the image may be a lot more complex—understood, perhaps, only by the artist himself.

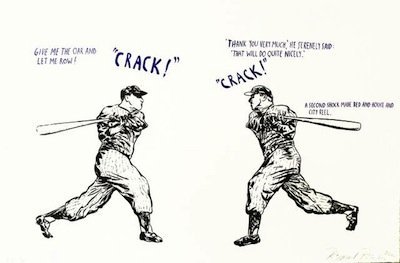

AMERICAN ANTIHEROES Mickey (2000)

Mickey (2000)

Even when Pettibon draws Gumby, a darkness that feels distinctly American lurks beneath his drawings. A few drawings pay homage to the serial killer Charles Manson (often in a disturbingly humorous way), and many more make light of violence—“O.D. a hippie,” reads the bolded text above an image of a gun-toting thief in one image. Even the images that feel familiar become unsettling in Pettibon’s oeuvre. Many of Pettibon’s most celebrated drawings look as if they were unused ideas for a Raymond Chandler novel. Noirish gangsters chat about their latest heists, and sexualized women are shown in peril. Even Jackie Robinson doesn't come out unscathed in Pettibon's Notorious B.I.G-quoting drawings, while Mickey Mantle (above) takes on a discordant veneer of desperation. If Pettibon’s drawings make anything clear, it’s that no American figures are quite as heroic as they appear.

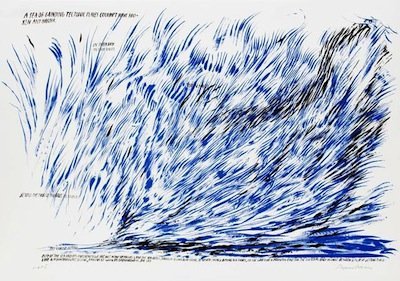

GOING WITH THE FLOW Untitled (A sea of grinding...) (2008)

Untitled (A sea of grinding...) (2008)

While the majority of Pettibon’s work has an attractively cynical bent, he does allow passing moments of beauty to intrude in his drawings, notably in his depictions of surfers at play on the ocean and colossal waves. For Pettibon, who was raised in California, surfing is personal, and the joy of the sport shines through in these sincere drawings of beautiful, overwhelming curls of blue. A less happy fate is in store for the surfers, however: They enjoy their moment of glory for a fleeting moment as they glide along the wave, but the second it crashes their state of grace is finished. Pettibon, however, captures that brief instance of sublimity and generously shares wit with us.