In 1968, a young artist from the Bronx laid out three rules:

1. THE ARTIST MAY CONSTRUCT THE PIECE.

2. THE PIECE MAY BE FABRICATED.

3. THE PIECE NEED NOT BE BUILT.

EACH BEING EQUAL AND CONSISTENT WITH THE INTENT OF THE ARTIST, THE DECISION AS TO CONDITION RESTS WITH THE RECEIVER UPON THE OCCASION OF RECEIVERSHIP

Art had always been whatever artists said it was. But with this, Lawrence Weiner broke with custom, boldly handing over artistic interpretation to the viewer. Sure, fellow conceptualists Robert Morris, Mel Bochner, Sol LeWitt, and Dan Graham had moved beyond the belief that art had to be a material object. But Weiner’s miniature manifesto theorized how this heady new immaterial art was able to exist in the world: the viewer completed it.

After writing this famed Statement of Intent, Weiner traded the paintbrush for the typewriter to make sculptures out of the most universal material of all, language. He has since gone on to create over 1,000 text pieces—cryptic phrases, parsed slogans—over his 50-year career. His goal, he has stated, is to fundamentally shift the way his viewers look at the world. How does Weiner do this with a 26-letter palette? Here, we take a closer look at the funny and fiercely democratic compositions of this language-based sculptor, who has emblazoned his typefaces onto everything from manhole covers in New York to Nazi-era towers in Austria.

EARLY WORK: WHAT IS SET UPON

THE TABLE SITS UPON THE TABLE

The son of a New York candy-store owner, Weiner graduated from Stuyvesant High School at 16, studied philosophy briefly at Hunter College, and spent “reasonable amounts of time in New York City lock-ups and holding tanks” until he hitchhiked across North America, landing in San Francisco, where he hung out with Beat poets at the landmark City Lights Bookstore. He hit the highway again in 1960, this time inspired by Jack Kerouac’s seminal On the Road, and left sculptures on the side of the highway along the way. “The Johnny Appleseed idea of art was perfect for me,” Weiner once said in an interview.

Half out of frustration with his limited artistic materials (he had been painting in an expressionistic mode), Weiner experimented the same year by setting off explosives in a state park north of San Francisco, leaving gaping craters across the earth’s surface—and opening up new possibilities in his art. He soon explored these further through What Is Set Upon the Table Sits Upon the Table(Stone on Table) (1960–1962), in which he moved a chunk of a limestone on a table after sculpting it. The central act here was the transference of material from one place to another.

SCULPTING LANGUAGE: TWO MINUTES OF SPRAY PAINT DIRECTLY UPON THE FLOOR FROM A STANDARD AEROSOL SPRAY CAN

How then did language become a material object for the artist? The eureka moment came with another act of destruction, in 1968, when Weiner was in a show with Carl Andre and Robert Barry at Windham College in Vermont. Weiner’s work consisted of a grid of low stakes linked with string across a grassy field on campus, which students quickly trampled down in a game of touch football. “When I got there and looked at it, it didn’t seem as if the philistines had done the work any particular harm,” he later said, because the Platonic ideal of the piece still existed in his mind in the form of its concept. Weiner realized that, by paring down his work to its most fundamental essence—its concept as expressed through language—he could reach anyone, evoke any image, incite any sort of action.

Take one of his earliest works, the 1968 sculpture Two minutes of spray paint directly upon the floor from a standard aerosol spray can. In the gallery setting, the work consisted of that title and a circular patch of thick spraypaint on the floor—but the piece truly existed in the language, and could be replicated by anyone with a can of spray paint, anywhere. (Or not—Weiner wasn’t interested in enforcing some kind of “aesthetic fascism.”) Now, instead of moving stone from one place to another, Weiner could bypass the scrim of material reality to convey something rawer to the viewer, through language.

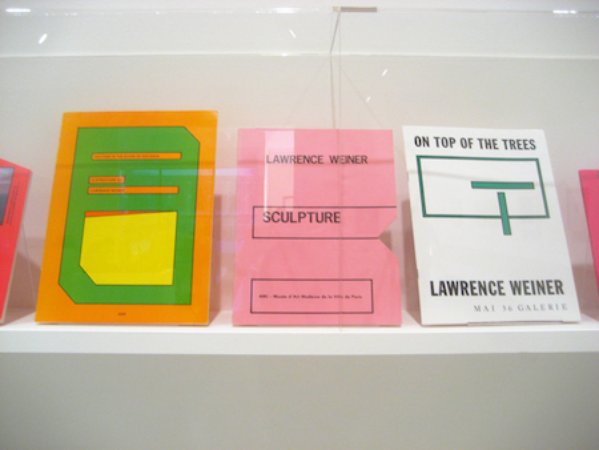

ARTIST BOOKS: TO PLACE AN INFORMAL OBJECT (THE ART) WITHIN A FORMAL CONSTRUCT (THE CUTLURE)

Language, Weiner was discovering, had an unbounded quality that a painting’s or a sculpture’s edge precluded. Since 1968, he has put out a staggering number of artist's books, more than 70. His words tend to lay out propositions, and they transcend the specific for the general. “To throw an object from one country to another” goes one, and “Illuminated by the light of two ships passing in the night,” another. Among Modernist poets, Weiner might most resemble Wallace Stevens in his simply expressed but densely concepted lines.

So, why aren’t these works considered poetry, you ask? Because words don't reveal an inner life—they fully embrace the material world. “Your personal enlightenment of your personal angst is not a fit subject for art,” Weiner has said. “It might be a fit subject for literature, or poetry perhaps, but art is about material objects.”

Some books are interspersed with photographs, like the 1973 Once Upon a Time with Giorgio Colombo’s pictures of Italy. But many go unaccompanied. “There is no analogy that I can make,” Weiner said in an interview with Bomb, explaining the naked words. “Because it’s not foreplay, it’s the whole thing: the immediate tactile response. There’s nothing—nothing—being held back. That’s all there is.” Weiner doesn't believe his text belong anywhere in particular. He's not precious about them. He's just passing information along in the manner of Johnny Appleseed, sowing his words wide and far to see if they'll burst through in the cracks of the reader’s mind.

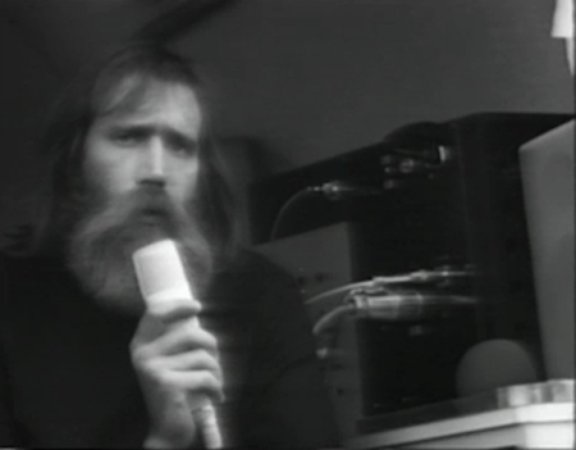

FILM: BROKEN OFF

In addition to text, performance and film has been an important medium to the artist. He made one especially compelling work, Broken Off, in 1971 with filmmaker Gerry Schum, and in it Weiner appears on a beach snapping branches, kicking at seagrass, and plying apart two wooden panels; the destruction continues until Weiner pulls the plug to the video camera itself. Subsequent iterations of the work “Broken Off” appear on matchbooks, paper, and broken bathroom tiles, and in an 1971 performance he made some stark postcards and took them to East Berlin, a place physically “broken off” from the rest of the city, and mailed them to people across the wall. The central act here again was dissemination.

Weiner's interest in performance and material forms of communication (ahem) also led him down the road of making pornographic films, beginning with “A Bit of Matter and a Little Bit More” (1976). The opening shot is a close-up of a woman and man having sex, followed by shots of objects, like a hammer and nail on the floor. “I’ve always seen myself as a basic materialist, which is why my films are so raunchy,” Weiner explained. Most recently, he shot an orgiastic conceptual group sex film "Water in Milk Exists" at New York's Swiss Institute in 2008.

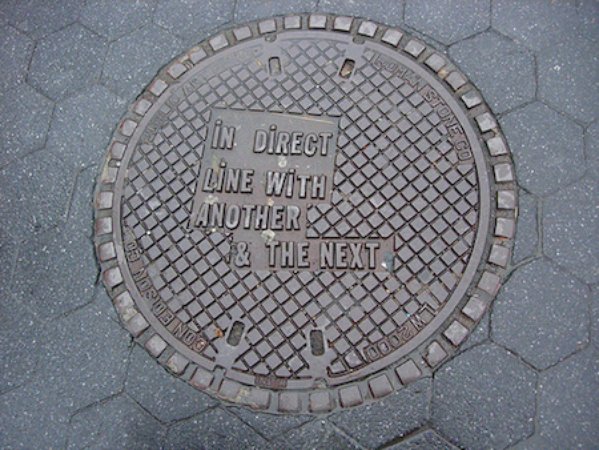

PUBLIC ART: IN DIRECT LINE WITH ANOTHER & THE NEXT

Sculpture’s original purpose, Weiner has contended, was to orient a person in relation to the sun. His words that appear in public places also orient, only in a kind of semantic space. On a Nazi-era defense tower, Weiner poignantly pointed to the history of pogroms, writing “Smashed to Pieces (in the Still of the Night)” (1991). On a freshly poured highway in Ballerup, Denmark, he recommended play as an alternative to the relentless industry: “Paper + stone or fire + water (when in doubt) play tick tac toe & hope for the best.” And in 2000, he collaborated with a fabricator to make cast-iron manhole covers across lower Manhattan, from Tompkins Square Park to a Greenwich Village nursing home. They read: “In direct line with another & the next”—a statement that layed out an abstract spatial concept and fulfilled it in three dimensions, mapping a new constellation across the city. With Weiner's art, we might not find our way, but can wander together, and, in our encounters, dare to make the work complete.