In his installations and mixed-media works, the French artist Christian Boltanski uses photography and found objects to question memory and individuality. An awareness of mortality, and of the general tenuousness of human existence, haunts his art. Boltanski has had solo exhibitions at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, the Centre Georges Pompidou Paris, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles.

In this excerpt from Phaidon's 1997 monograph, Boltanski talks with Tamar Garb about the problem of viewing art as a relic, how doing so had led museums to become "the new churches," and how he urinated on his famous biscuit tin pieces to give them that freshly rusted look.

...

Your work is about the self, about revealing the self, and about playing tantalizingly with the self. What I would like to know is: who is Christian Boltanski? Where are you in this elaborate ruse, in this series of tricks and artifices which you deploy?

I really think I am nobody. If you work as an artist, you destroy yourself. The more you work, the less you exist; and each time you do an interview a part of yourself disappears. It seems awful, but it can also be a good thing, since it's easier to make art than to live. It's a choice one makes.

But there is always an agent involved in the manipulations of self-effacement or display. Is there a puppeteer pulling the strings?

In my early work I pretended to speak about my childhood, yet my real childhood had disappeared. I have lied about it so often that I no longer have a real memory of this time, and my childhood has become, for me, some kind of universal childhood, not a real one. Everything you do is a pretense. My life is about making stories. I travel a lot; I'm like some kind of travelling circus clown.

Why then do you choose to tell certain stories rather than others?

At the beginning of all the work there is a kind of trauma: something happened. This might be a psychoanalytic problem. All your life you can be telling the same story, but then you can tell it in different ways—through poetry, through song, etc. For me, then, I feel that there are some very important things that occurred at the beginning and only afterwards could I speak about them. One always first tries to escape a problem rather than talk about it. When I was younger I was very crazy; now I’m very normal. I only do what I do now because I used to be crazy. Art for me is one way of talking about problems and about the past; sometimes, as with psychoanalysis, you are a little better for having done so.

Don’t you find yourself lapsing into a cliché though, like ‘crazy’ Van Gogh: the artist who can only act in a state of uncontrolled frenzy?

But it’s not totally uncontrolled; you have something in particular to say. Perhaps some artists would say it’s better to concentrate on art itself, whereas others would deal with life.

Where would you position yourself in relation to this?

Always in between the two. I am an artist at the end of the twentieth century, working with late twentieth-century means; a son of Minimal Art, born at a particular moment in this century. Had I been born ten years earlier, perhaps I might have been an Abstract Expressionist, although I don’t like abstract expressionist art very much. This raises the question: why do so many artists make more or less the same kind of art at any one time? There is an individuality, yet there is definitely an aura of the time.

You describe yourself as a painter, which is very intriguing. To be a painter, for you, is clearly not about the métier of painting; rather it’s about a form of consciousness.

Being a painter means speaking with visual things. But it’s also interesting to note the difference between filmmaking and painting. The question of time is the thing here. When you watch a video piece you can stand there for two seconds or two hours—there’s no beginning or end and you can move around while you’re doing it. When you see a film, on the other hand, you sit there watching it from beginning to end. In films, novels, and music there is always this issue of time; when you’re looking at a static image, there isn’t that progression.

There’s no catharsis, you don’t make that journey in time.

Yes. And I think that one of the reasons we cry when watching a film or a play is because of the suspense. The same goes for music; we might be listening to a work by Bach and, suddenly, there’ll be a moment of suspense. It shocks us; we never know exactly what is going to happen next.

Yes, but interestingly, the installation of your work is often very theatrical; it stages itself as an event through which you move in time. I wonder if that’s a way for you to create a sense of suspense and drama akin to the effect of cinema while using a still image.

When I create a show I always make the viewer aware that it has a beginning and an end. For a long time there were performances in art where people would just sit and look at something; but in the last five to ten years the spectator has become more of an actor. For example in The Ordinary Days (1996), which I did in Dresden with Jean Calman, we created a small dark corridor at the end of which was a very bright, blinding light. The spectator’s body was therefore also involved in the ‘viewing’: looking at something actually became part of the work. I also see this in other artists’ work, say in Bruce Nauman’s for example: the spectator’s body is inside the work. When my work was exhibited at Hamburg, the space was really good and gave the spectator the same feeling. One walked down a long narrow corridor and then arrived in a large room; the space showed the way, it directed the experience of viewing.

That almost duplicates a ritual procession, a route by which one travels through the experience.

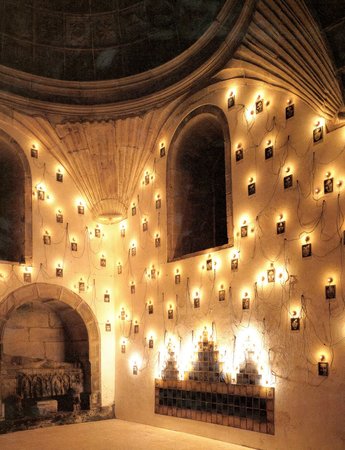

I am happiest with a show when the whole show is one big piece, when it’s not made up of different works. Like the installation Lessons of Darkness at the Chapelle de l’hôpital de la Salpêtrière, Paris (1985), and Advento at the Iglesia de San Domingos de Bonaval, in Santiago de Compostela, Spain (1995).

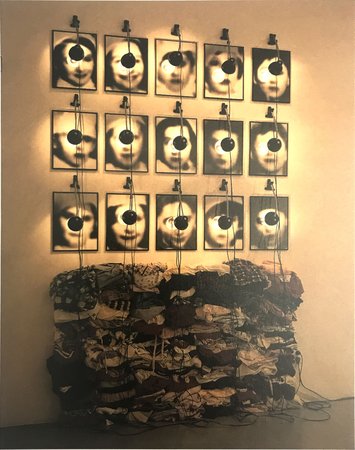

Christian Boltanski, Monument: The Children of Dijon, 1986

Christian Boltanski, Monument: The Children of Dijon, 1986

Yes, I think that’s very true, as there is something about the power of seeing a group of works together and their accumulated effect which is indispensable in your work—it completely alters it. Also, because of the lighting and theatricality, your work becomes almost religious, and it leads one to think about comparing that kind of space to a space of worship. One engages with the work in a space outside of everyday life, in a contemplative space which is also suggestive of a religious space.

I’m not religious, but I do think the earliest relationship we have with art is when we first go to church. Not because painting is there, but because of the presence of the priest, whose words and actions by some sort of abstraction tell us something very important. You are in the symbolic order and in the realm of the mysterious. The same occurs in painting. In the Middle Ages the town cathedral would keep the relics of its saint—rather like a museum today housing works of art. People would do pilgrimages to the cathedral and the town would earn its wealth from that. The new princes don’t build cathedrals anymore; they build museums. Museums today have become the new churches.

But who is the new God? It’s not art, because our culture doesn’t really revere art.

Yes, but think of collectors who pay a fortune for a Van Gogh: they want it because it was touched by a holy man—the artist. The artwork comes with so much religious mythology attached to it. People want art for all kinds of ‘religious’ reasons, thinking that the work will save them, make them better somehow, because the work is precious.

But do you feel comfortable with that idea of what the artist can be?

No. It’s true that I am very interested in religion and I also think that my art is very Christian. And if I wanted to be pretentious, I’d say doing the work is rather like being a Zen master, in that my work tells a story and asks questions. At the same time I think that the idea of the relic is completely stupid, especially in art today. In the late twentieth century, more than half of the art produced is not even touched by the artist. If I put my lighter on display at an exhibition, it would be acceptable. It would be on a pedestal and labeled, like a bronze sculpture. But what I have been trying to do for a few years now is to escape this idea of the relic. I remember when the Tate Gallery bought one of my pieces, Dead Swiss on Shelves with White Cotton. When I sold it, the curator mentioned that the cotton would go yellow in a few years time, so I told him that he could change it. He also said that the photos would fade, so I told him that’s okay, there are always more dead Swiss—I don’t care which ones you use. Moreover, even the shelves were not going to fit, so they had been made for a different room! And the curator asked, what did we buy? And I said well, you’ve bought photos of dead Swiss and shelves with white cotton. But it’s not an object, it’s an idea.

But would you expect then in ten years time to show the shadowed remains of that piece, or to renew it with new material?

I consider what I do to be like a musical score, and anyone can play it. But each time it’s played, it means something different. I remember doing a show once entitled ‘Do It,” curated by Hans-Ulrich Obrist which included Mike Kelley, Ilya Kabakov and Bertrand Lavier. Each of us had to describe a piece, then we all had to make these works and exhibit them. We also made a book and sent it to a number of museums and art centers, but the rule was that the artists couldn’t actually go to these places themselves. The museums had to interpret our descriptions. Sometimes it would work and sometimes it wouldn’t, but we didn’t actually control the outcome.

I did a show in New York at Grand Central Station about a year ago in which I showed about 3,000 objects that had been lost on the New York subway. If someone then wanted to do the same piece in Tokyo, it could be done with objects lost on the Tokyo trains. After the show the objects were sold, but the same show could still be done tomorrow. It’s the idea that’s important. Around half of the work I do is destroyed after each show, but the show can always be done again.

There is this issue of reincarnation. When someone plays a partita, the music is reincarnated, but in painting someone has to sign the piece. Glenn Gould played Bach, but the music was always Bach; with my work, it might be a Boltanski played by Mr. Smith. The work is not closed.

I’ve used a lot of biscuit tins in my work, and at the beginning they were more personal somehow because I peed on them to make them rust. But I was using so many boxes that I couldn’t do this any more, so I started using Coca Cola to rust them. They were easily replicable and easily rustable. I remember I exhibited them in Hamburg and in Oslo. The piece was sent there, each box wrapped in tissue paper, and when they arrived the curator demanded that all the workers wear white gloves. It was ridiculous because of course the gloves became red in minutes. And the biscuit tins aren’t precious.

Christian Boltanski, The Reserve of Dead Swiss, 1991

Christian Boltanski, The Reserve of Dead Swiss, 1991

Yes, but because of the way museums commodify their exhibits, these objects become precious within that context. It’s like the creation of a relic. It’s also about aura, and how the work becomes a magical, totemic object.

It seems to me that Western Christian culture is all about objects. For an African it is not so important to preserve a mask from the sixteenth century. What is important is to have someone now who still has the skill to make a mask. In many other traditions, it’s not important to keep the object, but what is of value is knowing the idea or story behind it. In Japan, the Zen temples are so fragile that they have to be rebuilt every ten years. But people there call these buildings monuments precisely because they know their story. So you have cultures of objects and cultures of knowledge.

In the West you have this acquisitive mentality, either as wealth or as totem.

Perhaps it’s better, though, to know the story.

Surely, though, at the origins of Christian art, in early medieval times, the object was thought to be the means by which one would tell the story. Now the story seems to have gone and the object has become a thing in itself. When you put your objects into glass cabinets to display them, you obviously invoke a number of different registers of the way in which the object is classified and used as evidence in Western culture.

At the beginning, I was very influenced by the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, which contains huge glass cabinets displaying dead cultures. Nobody really knows what all the different objects on display were actually used for. There are photos showing people of different cultures, but you look at the images knowing that these cultures are all dead. Each cabinet is like a large tomb. I think what I was trying to do in my work was to take strange objects—objects that we know have been used for something although we don’t know exactly for what—and show their strangeness. It has to do with individual mythology. The objects I display come from my own mythology; most of these things are now dead and impossible to understand. They might be insignificant things, or just simple and fragile, but people looking at them can imagine that they were once useful for something.

Often the objects you use invoke lives that have been lived and are now lost, gone. They stand for a death of somebody, maybe a victim.

Yes, there is something contradictory in my work, in that it is about relics but at the same time it’s very much against relics. Part of my work has been about what I call ‘small memory.’ Large memory is recorded in books and small memory is about little things: trivia, jokes. Part of my work then has been about trying to preserve ‘small memory,’ because often when someone ides, that memory disappears. Yet that ‘small memory’ is what makes people different from one another, unique. These memories are very fragile; I wanted to save them.

The relationship between objects and cults is interesting too. Like the cult of personality which our society is so obsessed with, and the way in which objects that are residues of a particular person’s life become infused with mystery, aura, magic, whatever.

For example, I often work on pieces that include clothes, and for me there is a direct relationship between a piece of clothing, a photo and a dead body, in that someone once existed but is no longer here. Every time I work on pieces like these there are always people who tell me that they can sympathize somehow with the use of these materials, because when their own mother or grandmother died they never knew what to do with their clothes and things. And especially with shoes, which have a particular link to the person who wore them. What is beautiful about working with used clothes is that these have really come from somebody. Someone has actually chosen them, loved them, but the life in them is now dead. Exhibiting them in a show is like giving the clothes a new life—like resurrecting them. Especially when you think that clothes can belong to such different people: it’s like a kind of resurrection.

Christian Boltanski, Reserves: The Purim Holiday, 1989

Christian Boltanski, Reserves: The Purim Holiday, 1989

But it need not necessarily invoke loss. In your piece Reserves: The Purim Holiday, which of course is related to the Jewish festival of Purim when children wear fancy dress, you invoke the whole fantasy of dressing up. An interest in costume and theater is suggested here. So the recycled clothes need not only to do with the mournful, melancholic residue of a dead life, but also with the rebirth that fancy dress involves.

I’m glad you’ve said that, because often people do view my art in a very mournful way, but I feel there’s a lot of humor in it. When I do a large piece with used clothes some people talk about it in relation to the Holocaust and say how sad the piece is. But children find it fun, it makes them happy, because they can try on all the clothes. I never speak directly about the Holocaust in my work, but of course my work comes after the Holocaust. You know, at the end of the nineteenth century people believed that science was going to save us. Now we can see that things have gotten worse: not only the Holocaust but Bosnia, Rwanda, the atom bomb, and then AIDS, pollution, mad cows…So we know that science isn’t going to save us, our big hope has been destroyed. The Holocaust taught me that we are no better now than we were in the past. All the hopes of human improvement and progress have been destroyed.

People say, however, that you don’t have to work directly about the Holocaust, because the Holocaust works through us. The Holocaust shapes the consciousness of most Europeans living in its aftermath. As Lyotard said, ‘We are all Jews after the Holocaust’.

Yes but there have been holocausts after the Holocaust. I’m not working on the issue of being guilty or not guilty. My work is about the fact of dying, but it’s not about the Holocaust itself. I made a book four or five years ago called Sans Souci. It’s a photo album which I bought at a flea market in Berlin. Some of these nice-looking people became Nazis. We see Christmas trees, music, babies: they were just like us. If the monster had been different from us, it would have been easier to deal with. But it was us. I did this book when I was in America, just after the Gulf War. I remember watching television and seeing the pilots returning from the Middle East; they were so young and sweet, kissing their girlfriends and babies, yet only the day before they had been killing women and children! It’s a book with no text, but if you ‘read’ it, it leaves you with a question. Perhaps this is the question about whether one is guilty or not guilty. About being a victim or criminal—or both. But not necessarily in the context of the Holocaust.

So the work involves the Holocaust while not necessarily being about the Holocaust. On the one hand you’re not Jewish and on the other hand you are Jewish. And the work is deeply marked by Jewish history, while at the same time it is profoundly Catholic.

I don’t think it’s about Jewish history. I often get this kind of misunderstanding with my work. Of course it is post-Holocaust art, but that is not the same as saying that it is Jewish art. I hope my work is general. I’m not a philosopher; I’m an artist. I make paintings.

I know nothing about Jewish culture and religion; I’ve almost never been to a synagogue. If I had to choose a religion I would choose the Christian religion. I think it would suit me better because it’s more universal than Judaism. The Jews never had an inquisition, for example, in order to convert people to Judaism. What is so beautiful and simultaneously dangerous about Christianity is that Christians want to convert everyone to their faith—so with the beauty of this ideal comes the fact that they’ve killed so many people. There is nothing more beautiful in Christianity than the fact that Christ was killed for everybody. Also Christ’s last words were incredible, they were: ‘I’m thirsty; Father, why have you forsaken me?,’ and “I’m dying’—which are all so human. It’s so amazing that a religion can be built on these word, the words of a man at the moment of such weakness and despair.

So when you deploy the lights and the candles and the shadows and imagery of death in your work, do you replay that Christian narrative in your mind? To what extent is that narrative being represented?

It’s not in the imagery, because the imagery I use could evoke many different religions. I use religion as a vehicle through which to speak, that is true. I think that if my art is Christian it is because I believe that everybody is different—but that is probably equally Jewish. And while everybody looks the same, everybody is unique. Politicians will talk about fatalities in a war in large numbers but each person who dies has a mother or a girlfriend and is a unique being. Deaths must be counted in ones. Christianity seems to me to place an emphasis on the individual in a very special way.

But at the same time while you suggest individualism in your work, you obliterate it, especially when you use the lights that shine on the faces which become cadavers. You invoke an individual, lived life but at the same time obliterate it by the blinding light. It’s different from the mysterious light of the candles; it makes me think of torture.

A good work can never be read in one way. My work is full of contradictions. An artwork is open—it is the spectators looking at the work who make the piece, using their own background. A lamp in my work might make you think of a police interrogation, but it’s also religious, like a candle. At the same time it alludes to a precious painting, with a single light shining on it. There are many ways of looking at the work. It has to be ‘unfocused’ somehow so that everyone can recognize something of their own self while viewing it.

The candle functioning in that way reminds me on the one hand of the atmosphere of a Catholic church, but it is equally evocative of the menorah and the flickering lights at Hanukkah. It could work in either context.

I always try to use forms that people can recognize. Take the biscuit tins for example. I use them because they are minimal objects, but also because I know that my generation can recognize them. We have all kept our small treasures in biscuit tins. It also reminds some people of the mental urns where ashes are kept. I suppose I want my art to be more about recognition than discovery.

The big problem in art is being able to tell the story of your own village, while at the same time having your village become everyone’s village. I want to be faceless. I hold a mirror to my face so that those who look at me see themselves and therefore I disappear.

Christian Boltanski, The Candles, 1986

Christian Boltanski, The Candles, 1986