Textbooks tend to organize art history chronologically. But what if we re-told art history through color instead? Color is more than just a wavelength on a spectrum; colors are ideologically charged with cultural symbolism, metaphor, and ritual, and each one has a material history that can tell us about economic and international exchange. In this excerpt from Phaidon 's Chromaphilia: The Story of Color in Art , reading art history against the grain of red reveals conceptual, psychological and cultural differences between Donald Judd , Louise Bourgeois , and Anish Kapoor .

...

Not all colors are equal, and their values shift with cultural and chronological contexts. While earth colors are broadly ubiquitous, with red we explore concepts of rarity and exclusivity. With these come perceptions of taste, status, excess, and control, all of which are wrapped in color.

Exotic or dangerous sourcing of red pigment, such as that used in frescoes at Pompeii’s opulent Villa of the Mysteries, provoked commentary and disagreement among ancient authors. In later European culture, the creation of color sometimes entailed complex, semi-secretive procedures and belief systems, as in the connections between vermilion and alchemy. The red dyes used to color sumptuous cloth worn by the wealthy and powerful in societies from South America to Europe reveal habits of behavior and associated color regulations that controlled both industries and individuals. Murúa’s sketches of Peruvian royal costume are an analog to images of luxurious red cloth shown in paintings by Fra Filippo Lippi and van Eyck. Further color canons involving the use of red clothing are reflected in works by El Greco and Velásquez, having been codified in a religious context. A consideration of the function of color in art should never be merely an examination of systems and rules, however. To reinforce the significant afterlife of great works of art in the creation of new art, paintings by Bacon and Finch analyze, appropriate and reflect on Velásquez to produce their own expressions in red.

Artistic practice shapes and is shaped by ideology. In different cultures or period, a particular characteristic of color will be favored. Fra Angelico’s uncorrupted saturated reds reveal one of these intrinsic aspects of color, and suggest underlying notions oa bout purity that might inform ways that color are mixed or kept separate. Different binders—in egg-based tempera paints versus oil paints—carry optical, aesthetic, and philosophical effects.

Red in art is loaded with symbolic connotations that are both broadly cultural and idiosyncratically personal. Lorenzetti’s and Rubens’s red play their role as approved metaphors for cherished values. El Lissitzky’s red, on the other hand, is redolent of revolution. For the other twentieth- and twenty-first century works examined here, the varied meanings of red are fluid yet assertive perspectives of the individual artists. Whether representing personal or political histories, emotion, or social commentary, red has a powerful metaphorical pull. As a counterpoint, some artists have taken a strong ideological stand about color and yet resist its metaphorical expression. They include Mondrian , with his search for universal harmonies, and Newman, engaged in his own oppositional search. Judd’s use of red, in contrast to both, is a resolute rejection of all symbolic connections.

When red is lightened by the addition of white, it becomes a completely different color that carries its own coding. Pink’s evocations in art, from sex and play to threat and violence, take us to a new sphere, one associated with—yet no longer— red .

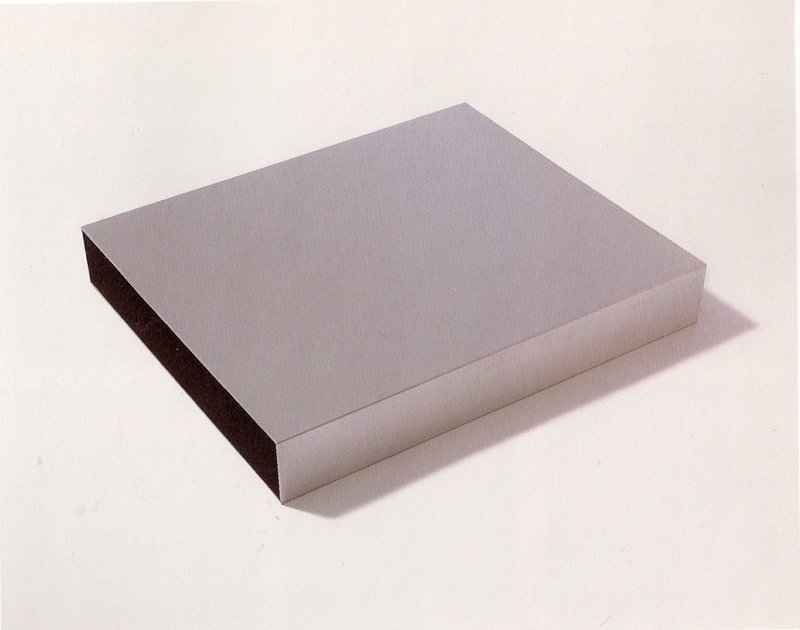

Donald Judd,

Untitled

, 1963

Donald Judd,

Untitled

, 1963

“Color is never unimportant,” according to Donald Judd. He paired down his art to its limits, stripping away anything he considered extraneous to its self-sufficient identity as an art object: no illusionism, no allusions to emotion or metaphor, no conventional aesthetic or composition judgment.

An art of such distillation makes special demands on color, lest it be a distraction. Judd considered color and space to occur together, not independently: form and color are interlocked as a single entity. For Judd, color needed to be non0relational, denoting nothing other than itself with no external references. He sought color that would confirm and reinforce the specificity of his objects, and found that light cadmium red was the one color that served his purpose. Whereas black has a tendency to blur boundaries, for Judd, cadmium red delimits them. The role of color was to clarify, not obscure, and after much thought Judd determined that this particular color provided the best terms.

Donald Judd's

Untitled (Schellman # M-3)

, 1971 is available here on Artspace

Donald Judd's

Untitled (Schellman # M-3)

, 1971 is available here on Artspace

Louise Bourgeois, The Red Room (Child), 1994

Louise Bourgeois, The Red Room (Child), 1994

Bourgeois said that “Color is stronger than language. It’s a subliminal communication.” Here, red suffuses an entire environment of found and made objects, viscerally communicating the effects of a profoundly uncomfortable psychic space. Color plays the key role in carrying a message of fear, anxiety, danger, and vulnerability.

The Red Room (Child) addresses childhood trauma. Bourgeois readily spoke of her own seminal ordeals, asserting that everything she did was inspired by her early life. A household with parents at odds with one another, a father’s sexual infidelities, a mother’s illnesses, and a child’s role as nurse, voyeur, and bearer of secrets all inform Bourgeois’ artistic vocabulary of symbolic motifs an color. Bourgeois called her room-like sculptures “cells,” a word with multiple meanings. Little rooms can confine or protect as either prisons or refuges. “Cell” also relates to the human body and blood. The intense red of this room is akin to a bloodbath, an open wound from childhood still scaring the adult mind. Glossy red body parts are displayed on pedestals or shelves along with other, mostly red, objects. Some parts are recognizable as diesembodied hands or arms in various positions, alone or holding one another in groups. Other red objects look as though they come from inside a human body, vaguely resembling internal organs. Bourgeois observed that our bodies are more than the sum of their parts, and here she makes us consider what that means.

Bourgeois described her mode as “destroy, rebuild, and destroy again.” She made conflict, fears, and intimate secrets visually manifest. The insistent red, symbolic of emotional intensity, is integral to her expression: “Red is an affirmation at any cost—regardless of the dangers in fighting—of contradiction, of aggression.”

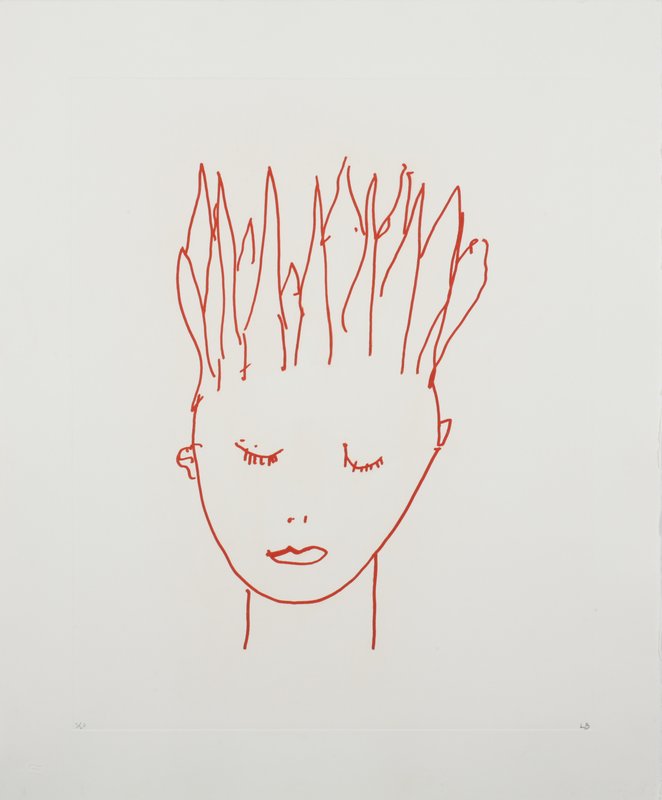

Louise Bourgeois's

Your head is on fire

, 2008 is available here on Artspace

Louise Bourgeois's

Your head is on fire

, 2008 is available here on Artspace

Anish Kapoor,

Mother as Mountain

, 1985

Anish Kapoor,

Mother as Mountain

, 1985

Color is tangible for Anish Kapoor—not mere surface coating, but substantial matter. Whether compromised of loose particles of fine dust or viscous blocks of wax, his materials make color physically manifest. Kapoor’s reds are intense, and such insistent color suggests extended cultural and personal symbolism. For Kapoor, “Red is the color of the earth, it’s not a color of deep space; it’s obviously the color of blood and body. I have a feeling that the darkness it reveals is as much deeper and darker darkness than that of blue or

Color is shaped to suggest fertile origins in Mother as Mountain . It is not a narrative, nor is its form explicit, but the red mound evokes both a geological formation and a woman’s genitals. Kapopr layers multiple allusions just as he provokes many questions: how is it made? Is it solid? What appears to be a delicate pile of loose powder is a carefully built structure supporting its skin of pigment. Dense, billowy, matte powder was applied methodically, almost ritually. This poetic ritual is not out of place, for Kapoor’s red draws from numerous traditions both Western and Hindu. The Indian springtime festival of Holi, the festival of color, is an exuberant celebration of spring’s arrival in which crows of people throw intensely colored powders from medicinal hers. In the days and weeks leading up to the event, massive piles of brightly colored powders are sold everywhere. Kapoor’s heap of red suggests this and more, but not as a direct correlate. Kapoor celebrates color’s completely nonverbal nature with proto-verbal symbolism. Without even needing words or articulated thought, color functions as a direct and visceral route to metaphor.

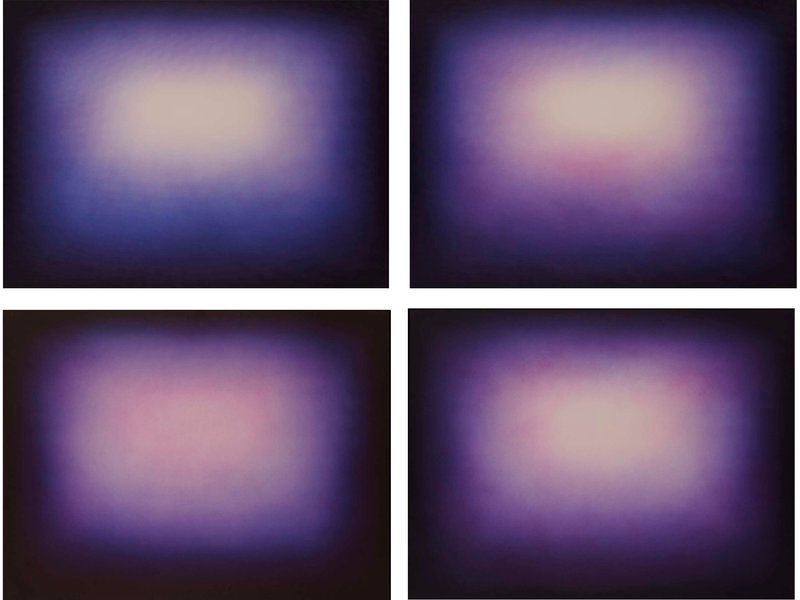

Anish Kapoor's

Shadow V (Purple)

, 2012 is available here on Artspace

Anish Kapoor's

Shadow V (Purple)

, 2012 is available here on Artspace