We have all heard tell of the ear, the mental instability, seen then snapped our annoyingly necessary selfies with Starry Night, but to better understand Vincent van Gogh is to push past the surface mythos and delve into a wider understanding of his art and personal history. The great Dutch master of modernity lived a famously tortured life (thanks to a series of letters between himself and his art-dealer brother, Theo, a substantial personal history remains). He sought truth and reason through the combined means of religion and visual art and ended his short but brilliant existence in 1890, after his two most prolific years. He left us, thankfully, an oeuvre of paintings which inarguably progressed the direction and vision of western art. Lets take a minute to investigate 10 lesser-known masterpieces found immaculately reproduced in Phaidon’s monograph, Van Gogh.

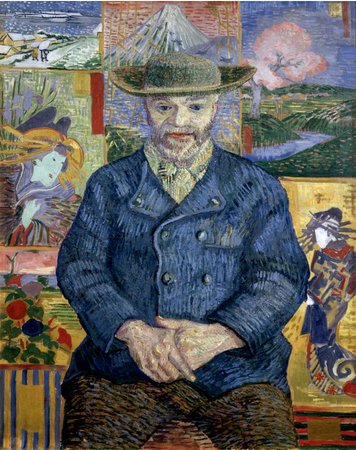

1. PÈRE TANGUY, 1887

The sitter in this portrait was the color merchant Julien Tanguy, a Breton peasant who had settled in Paris and ran a small paint shop in the Rue Clauzel, much frequented by vanguard artists. His shop became a kind of gallery of their paintings, for Tanguy would take paintings on deposit as credit for the materials he supplied. Van Gogh painted two portraits of “Père” Tanguy in the autumn and early winter of 1887, both against a background composed of the Japanese color woodcuts that he had begun to collect, first in Antwerp and then more avidly in Paris. Tanguy is placed massively in the center of the canvas, facing the spectator. But the Paris merchant is presented not against an urban or even French setting, but in an imaginary context composed of Japanese seasonal scenes and costumed figures.

Although this choice of background indicates van Gogh’s evident preoccupation with Japanese prints—he also made individual copies of selected print at this date—the painting does not indicate any profound influence of Japanese graphic styles or perspectival devices upon his work. But it is important to note that the motifs represented in the prints anticipate those that van Gogh would shortly resume when he left Paris and moved once again into a more rural setting—seasonal landscapes and portraits of regional types in costume.

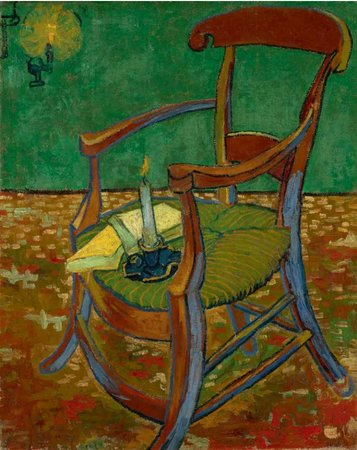

2. GAUGUIN ’S CHAIR, 1888

In October 1888 van Gogh realized a long-cherished plan to persuade Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), whose acquaintance he had made in Paris, to come to Arles, stay in the Yellow House, and help found a Studio of the South. Gauguin had been working in Brittany with Émile Bernard (1868–1941) and several other Parisian painters, and van Gogh had kept in close contact with this group through his correspondence with Bernard and by exchanges of work. He attempted to extend this system of exchanging information by encouraging Gauguin and Bernard to paint portraits of each other to send to him; he would paint a self-portrait for them. In the end Gauguin and Bernard did the same and sent him self-portraits. All the paintings in this project had the status of an artistic manifesto. Gauguin’s made a literary reference by incorporating the title of Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables (1862) and suggesting Gauguin’s identification with its hero, Jean Valjean.

In early December 1888 van Gogh began a pair of pendant paintings of chairs, Gauguin’s and his own. These pictures are not just great still lifes, however much the iconography is reminiscent of the allegorical use of motifs in seventeenth-century Dutch still life. The flame of a candle, for instance, is a commonplace in these, symbolizing light and life. But these paintings are also oblique portraits. On Gauguin’s chair van Gogh has placed two books, recognizable from the color of their covers as contemporary French novels. On his own chair he has placed a pipe and a tobacco pouch, and in the background there are sprouting onions. Gauguin’s Chair is a night scene; his own, a daylight scene. There is a further level of connotation in this pair of paintings.

In 1883 van Gogh told his brother of a story he had read about the English novelist Charles Dickens (1812–70) and the illustrator Luke Fildes (1843–1927). When Dickens died, Fildes made a drawing that was reproduced in The Graphic, an illustrated periodical the engravings in which van Gogh collected. The drawing showed Dickens’ workroom and now empty chair. Van Gogh explained to his brother what this image signified to him: he saw it as a symbol of the loss, through death, of the great pioneers of literature and graphic illustration. Moreover, these men— especially the illustrators, who had created images to accompany and illustrate modern literature—had, so van Gogh believed, worked in a collaborative and communal spirit. Their artistic community and shared endeavors provided him with a model for his own dream of a new co-operative society of artists based on the Studio of the South, which had been initiated by Gauguin’s arrival in Arles.

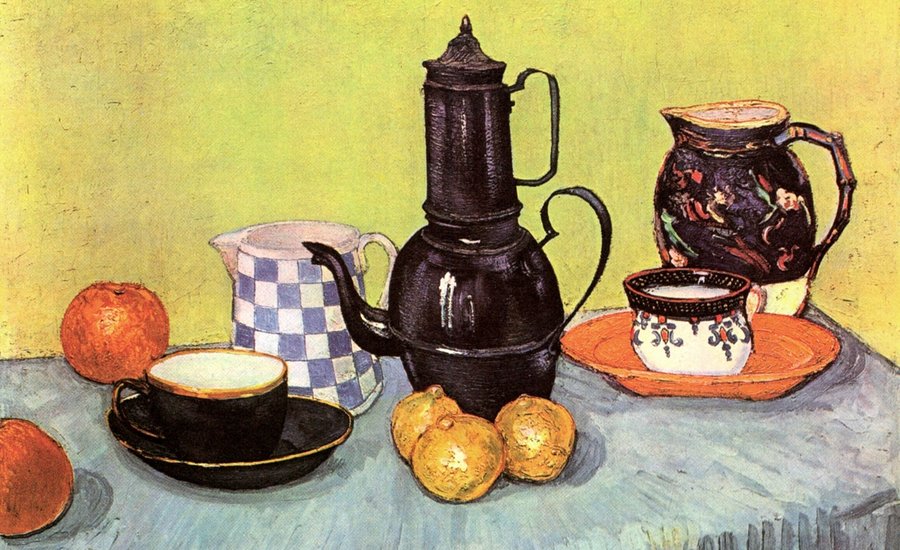

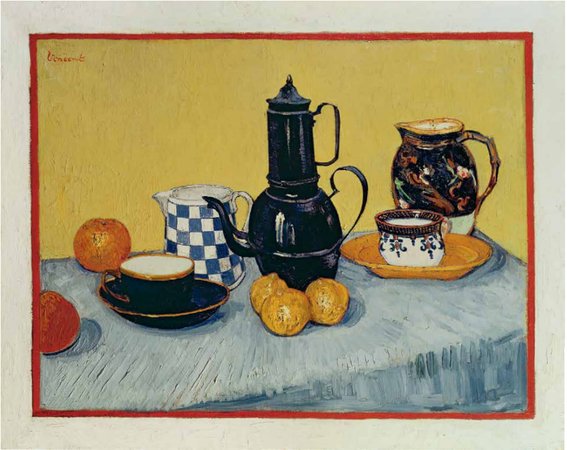

3. STILL LIFE WITH BLUE ENAMEL COFFEEPOT, EARTHENWARE, AND FRUIT, 1888

In his Dutch years, van Gogh had employed a tonal palette typical of the Barbizon painters and some of The Hague School artists. But in the years 1884 and 1885 he encountered a new theory of color in the books and articles he was reading about the French painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863). From these texts he derived the thesis that one of the distinguishing features and great discoveries of recent art that made it “modern” was the use of complementary and contrasting colors in place of tonality and chiaroscuro. The basic message of his reading was that each primary color—red, blue, yellow—has a complementary color composed of a mixture of the other two. The complement of red is green; of blue, orange; of yellow, violet. Shadows cast by an object should include a complementary color of the object. Complementaries are also used to heighten and intensify the brilliance of color. In his ambition to be modern, van Gogh adopted these theories, but without a sophisticated understanding of them or a sound technical foundation as a painter. He applied them crudely and programmatically, though often with unexpectedly powerful and original effects.

During the spring and summer of 1888 he corresponded regularly with Émile Bernard, giving his friend reports on work in progress and describing his color experiments such as this still life. The complementary pairs of blue and orange, yellow and violet, can be easily recognized in this painting, and from the color notes added to a sketch of it, included in a letter to Bernard, it is clear that the red and green pair was also employed. The background, which in reproduction appears yellow, was in fact a greenish tone. Around the picture, van Gogh has painted a red border, which serves to heighten and emphasize that green. The practice of painting a border of complementary color on to the canvas was initiated by Seurat, who also employed modern color theory.

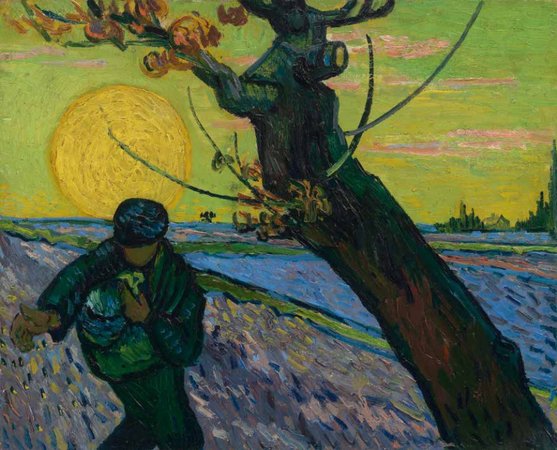

4. THE SOWER, 1888

Van Gogh has painted an autumnal scene of sowing. The motif of the peasant sowing had fascinated him since his earliest months as an artist. In 1880 and 1881 he had made many copies of an etching he owned after one of the most famous paintings of a sower by Jean-François Millet (1814–75), as well as composing his own drawings of the theme. He returned to the subject in June 1888, when he painted a landscape with a small figure of a sower in a field, dominated by a huge sun. In letters written in June he referred directly to Millet’s Sower, but he complained that it lacked color. It was one of van Gogh’s aims to correct this, in a sense to update the subject Millet had made so famous and which was for van Gogh so resonant, by repainting the motif using modern color theory.

The canvas was planned in the yellows and violets, though it did not finally conform to that scheme. In the autumn he resumed The Sower, making two paintings, of which this one is a smaller and probably later version. He has used violet and yellow. The appeal of the sower motif for van Gogh was complex. It signified Millet, and van Gogh’s allegiance to what he had stood for—rural scenes in modern art; it signified the seasons and cycles of life and work. But it also referred to the Bible, especially the parable, a particular way of using a commonplace story to convey allegorical meaning. Finally, it evoked modern literature, for instance Émile Zola’s recent novel La Terre (1888), which is structured round the cycles of sowing and harvesting. In July 1889 van Gogh painted the complement to his sower, The Reaper, also in violet and yellow tones.

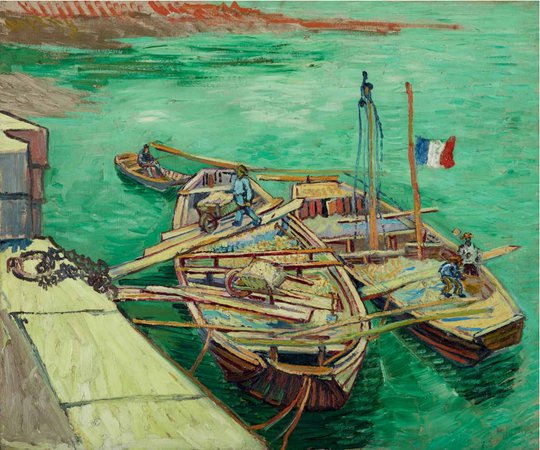

5. QUAY WITH MEN UNLOADING SAND BARGES, 1888

The town of Arles is on the Rhône, and that busy waterway appears in a number of van Gogh’s works. He painted the quayside with stevedores at work as well as more panoramic views of the river as it sweeps its way through the town. But in such works there is something stylized and remote about his treatment, as if it was difficult to come to terms with this aspect of Arles. There is a quality of ambivalence reminiscent of Monet’s evasive treatment of signs of modern labor and industry on the banks of the Seine near Argenteuil.

The painting is curious. The barges and their workmen are solidly and attentively painted, but the setting is minimal and unfinished. Nothing indicates exactly where this is all taking place. A small stretch of quayside suddenly gives way to a sketchy riverbank, a beach even. Beside the barges a man in a rowing boat is fishing, but his relation in space and scale to the barges is not clear. Van Gogh sent the painting to his friend and fellow artist Émile Bernard. In the accompanying letter, van Gogh admitted that the painting was only an attempt at a picture, and he stressed that although it was painted directly from life, it was not in the least "impressionist. " Perhaps van Gogh was intending to take on the older Impressionists such as Monet on their own territory—using their subject matter—and to transform the scene by a more solid handling and greater solidity of form. But apart from the foreground this has hardly been accomplished.

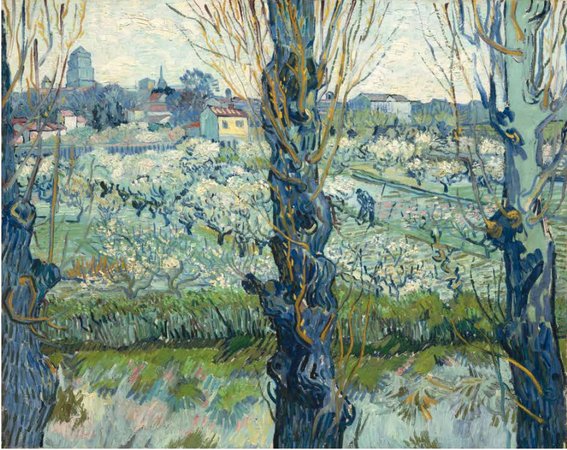

6. VIEW OF ARLES WITH ORCHARDS, 1889

In April 1889, shortly before he left Arles, van Gogh painted this view of the town, seen over the blossoming orchards and gardens and through a screen of tall trees. This image of the town differs from those he produced in the early months of his stay. Neither the agricultural environs of wheat fields nor the industrial landmarks of gas tanks and railway lines are depicted. Instead, we see an old, medieval Arles, surrounded by its cultivated and fertile gardens.

The sense of enclosure and fruitfulness, dreaminess even, has parallels in the illustrations of the medieval devotional books of hours, such as the Très Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry. Van Gogh selected this painting, which he titled Orchards in Bloom (Arles), for exhibition with the Belgian vanguard group Les XX in Brussels in 1890. He exhibited three times with the Parisian Indépendants: in 1888 he showed two paintings, two in 1889, and ten in 1890. To Brussels he sent four pictures: two canvases of sunflowers, a field of wheat at sunrise, and The Red Vineyard, which was bought by the Belgian artist Anna Boch (1848–1936). To accompany the exhibition the organ of Les XX, the magazine L’Art Moderne, published extracts from the lengthy and enthusiastic essay on van Gogh by Albert Aurier (1865–92), first published in 1890 in the Mercure de France newspaper.

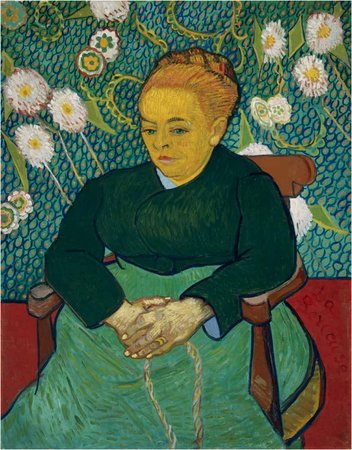

7. LA BERCEUSE LULLABY: MADAME AUGUSTINE ROULIN ROCKING A CRADLE, 1889

The portrait of the postman’s wife, recently delivered of her third child, was planned in late 1888 but only completed, after some interruptions, in early 1889. The conception of the painting, originally one of a series of family portraits, changed as a result of Gauguin’s visit in the autumn of 1888. In it he examined an alternative strategy for infusing a portrait with complex meanings. He gave the portrait a title, La Berceuse, which can mean both the woman who rocks the cradle and the lullaby she would sing beside it. Madame Roulin is represented primarily as the mother; she holds a cradle rope between her hands. Van Gogh supplemented this reading of the work in his letters by mentioning a Pierre Loti novel, Pêcheur d’Islande (An Iceland Fisherman, 1886), in which the author described the comfort and remembrances of home brought to isolated Breton fishermen by the crude old faience Madonna that stood in the cabin of their fishing boat.

La Berceuse was a significant work for van Gogh. He painted five versions of it, one of which was given to the sitter. He offered versions to Gauguin and Bernard and suggested a special setting for the painting, flanked by twin canvases of sunflowers whose brilliant yellow warmth was to underscore the feeling of gratitude that the painting was intended to convey. However, when he later turned his back on Gauguin and Bernard and the ideas that they had encouraged him to pursue, van Gogh also rejected this portrait.

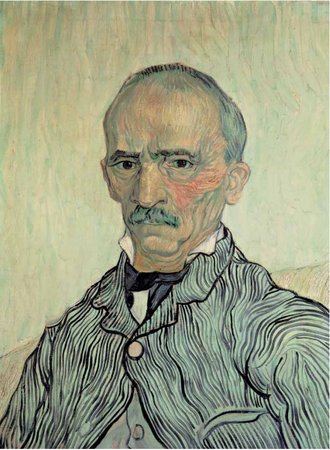

8. PORTRAIT OF SUPERINTENDENT TRABUC IN SAINT PAUL’S HOSPITAL, 1889

Van Gogh was able to paint some portraits during his stay in the hospital at Saint-Rémy. The hospital attendant and his wife both sat for him, which is convincing evidence of his epileptic rather than psychotic condition. Who would leave his wife alone with a madman? The couple provided van Gogh with another opportunity to paint a pendant pair of marital portraits. Of Madame Trabuc’s portrait, van Gogh wrote that he had painted her as a faded, withered woman, like a dusty blade of grass. The color scheme was pink and black. The attendant himself is portrayed with considerable force and presence in this bold and monumental portrait. The figure is placed frontally, set solidly in space against a background of delicately textured brushwork. The face is carefully painted with a different pattern of brushstrokes, which describe the contours of the forehead and skull and record all the cavities and slackness of the old man’s aging skin. The palette is softened and harmonious. As a portrait, it is one of Van Gogh’s most masterful, technically accomplished and controlled. He described the sitter to his brother, delighting in the fact that he had “something military in his small, quick black eyes.”

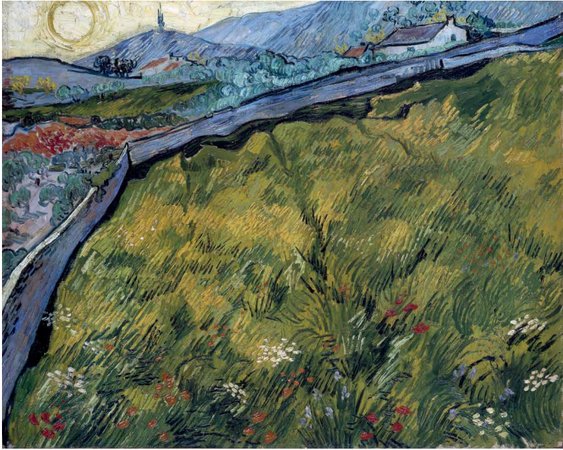

9. ENCLOSED WHEAT FIELD WITH RISING SUN, 1889

Van Gogh often painted this view from his hospital window at Saint-Rémy, using the window itself as a sort of perspective frame. He had tried to master the laws of correct perspective by reading textbooks on the subject, and in The Hague he had had a perspective frame made to help him in achieving it. The device is merely an empty frame, across which a grid of strings is drawn. This grid is also drawn on to the canvas or page. The artist looks at the motif through the frame, siting the scene and its objects in relation to the strings and then drawing or painting them in a corresponding position on the squared-up page or canvas. The point at which the strings cross provides the vanishing point, an imaginary point of distance which should match, in a mirror-like fashion, the viewpoint of the spectator. By this means a three-dimensional scene is transferred to a two-dimensional plane, and the space, perceived from this artificial, single viewpoint, is organized to appear logical and coherent, a kind of window on the world.

However, if, as van Gogh was given to doing, the artist deviates from the single viewpoint, looking above, below, or to the sides of the perspective frame and thus incorporating many viewpoints, the effect can be quite disarming, as is the case in this painting. The foreground and background do not match. The foreground, painted as if the grass and poppies are immediately beneath our feet, seems to tilt and slide forwards and downwards, thwarting the intended planar recession to the infinitely more distant background. The deviations from traditional geometric systems for representing space, created by Van Gogh’s unsystematic use of these systems, serve, however, to produce an effect of dynamic space and immediacy.

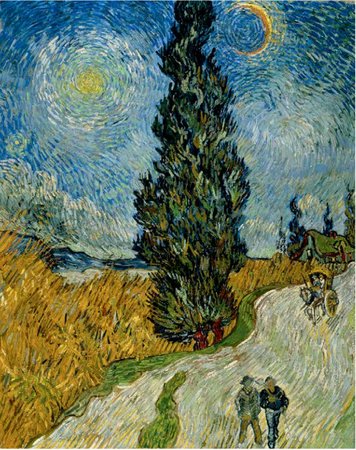

10. ROAD WITH CYPRESS AND STAR (COUNTRY ROAD IN PROVENCE BY NIGHT), 1890

Why was van Gogh investigating the roots of his practice during the time he spent at Saint Rémy? This painting provides some clues. After leaving Holland and moving to France, he had attempted to situate himself in relation to such Parisian painters as Bernard and Gauguin. He had corresponded and exchanged work with the former and, in a sense, studied with the latter in late 1888. He felt that they all three shared a dissatisfaction with Impressionism and its successors and a common purpose in creating what he called “la peinture consolante”—painting of consolation.

In June 1889 van Gogh painted a picture he called Starry Sky (now known as The Starry Night), an imaginative composition not painted from nature or the motif but composed from various sites and scenes of Brabant and Provence. He offered it to Bernard and Gauguin as his demonstration of a new form of religious painting. Both ignored the picture and thus overlooked van Gogh’s most ambitious painting in his French period, which had been conceived with reference to their joint concerns. Van Gogh responded to this cruel blow by angrily rejecting their work and the directions they had encouraged him to take. In June 1890, in a rare letter to Gauguin, he mentioned Road with Cypress and Star. He called it a “last attempt” at a star painting. It shares many features and motifs with the disregarded Starry Sky—a crescent moon, stars in the sky, Brabant cottages with lighted windows, a tall, solitary cypress. But there is no church; the theme has been “secularized.” It is just a landscape with cottages, trees, wheat fields and workers. It signifies a decisive retrenchment and a rejection of his flirtation with the Paris vanguard.