One of the most important and wide-ranging paradigm shifts to arise out of the social, political, and aesthetic upheavals of the 20 th century is a sustained, visible challenge to the outdated notion of a hard and fast gender binary. As usual, artists have been at the forefront of these changes, creating works that question the normative assumptions of what our bodies should look like or do while drawing from a variety of perspectives on the subject. These divergent representations are far from a modern development, however—as these excerpts from Phaidon’s Body of Art show, inquiries into the complexities of sex and gender transcend both time and place, making this a vital if sadly under-theorized facet of art history.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon's Body of Art and buy the book.

SLEEPING HERMAPHRODITOS

Artist Unknown

3

rd

-1

st

Century B.C.

The sexual ambivalence of the Sleeping Hermaphrodito s is more disquieting today than it would have been to ancient viewers, who knew the history of this son of Hermes and Aphrodite. For Hermaphroditos had rejected the advances of the nymph Salmacis, and she, in her distress, asked Zeus to merge their two bodies into one forever, hence the strange union of voluptuous female curves with male genitalia. The late Hellenistic date for the original work from which this Roman copy was made is based on the theatricality of the work: a first impression of a sensuous female nude, and then a surprise on the other side, rendered in realistic detail. The sculpture was discovered in Rome in 1608 and immediately became part of the Borghese collection. Its intrinsic eroticism was intensified in 1619 when Cardinal Scipione Borghese commissioned Gianlorenzo Bernini to sculpt the tufted mattress on which Hermaphroditos sleeps. The torsion of the figure’s body and the slightly raised left foot suggest an impression of restless dreaming, however, rather than deep sleep; the art historian Kenneth Clark saw this work as the direct inspiration for Velázquez’s decidedly alert Rokeby Venus.

GUANYIN OF THE SOUTHERN SEA

Artist Unknown

11

th

–12

th

Century A.D.

One of the most revered deities in Chinese Buddhism, Guanyin (the Chinese version of the Sanskrit Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara) is a goddess of mercy, compassion and unconditional love. Like all Bodhisattvas, she has postponed her own entry into nirvana until all beings have achieved enlightenment, but she in particular is seen as a savior, taking on any form necessary to assist those in need. This magnificent polychrome representation dates from the turn of the first millennium ad – the moment at which the male god began to turn into a goddess. Before the Song period (960–1279), Guanyin was portrayed with a moustache and distinctively male features, but around the time of the carving of this sculpture, the moustache disappeared and such feminine features as breasts and a softer, rounder face were assumed. This figure is still demonstrably male in posture and bearing, but the soft folds of the neck and the curving flesh of the chest exemplify the transition. In the figure’s relaxed, confident position, a female receptiveness is combined with male self-assurance, open to the entreaties of those in need. Apart from the right forearm and a small outcrop of the rockery, the sculpture is carved from a single piece of wood.

THE BEARDED WOMAN (MAGDALENA VENTURA WITH HER HUSBAND)

Jusepe de Ribera

1631

Two full-length figures, lit from the side in an otherwise darkened space, face us directly. Both are bearded; one, positioned slightly in front of the other, has a bare breast exposed and is suckling a child. Ribera (1591–1652) painted this work on commission to the Duke of Alcalá, who collected images of bizarre subjects for his own amusement. The female subject, Magdalena Ventura, was in her early fifties at the time, and was well known for her masculine features and long beard. The Latin inscription on the plinth to the right describes her as “a great wonder of nature.” Ventura bore three sons, although all were grown by the time this painting was made; the baby at her breast is perhaps symbolic of her maternity, as are the bobbin and the shell lying on top of the plinth. Despite the Duke’s perhaps puerile interest in the ostensibly abnormal subject, Ribera’s depiction of the sitters is both grave and sympathetic. The air of solemnity, generated by the somber, murky palette, is anything but mocking. The direct gazes, serious expressions, and forceful presence of the figures lend them a rare dignity.

PRINCESS X

Constantin Brancusi

1915–16

Despite accusations to the contrary, Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957) insisted that Princess X was a portrayal of a feminine ideal: a gently inclined oval face and graceful neck above a pert and generous bosom. Nonetheless, the sculpture was removed from the Salon des Indépendants in 1920 on the grounds of obscenity. Outraged by the suggestion that the work could be interpreted as anything else, the artist identified it as a portrait of a voluptuous ex-lover, with the highly polished bronze surface intended as a literal refection of female vanity and her habit of frequently checking her appearance in a mirror. Artist protestations aside, the sculpture undeniably presents a duality of gender, and depending on the angle from which it is viewed, different masculine or feminine attributes push their way to the fore. From the left front the form appears more upright and the breasts more prominent, while viewed from the right the piece appears more C-shaped and takes on the semblance of an erect penis and testicles. Curators have noted that Brancusi’s own photographic records of the work in the studio almost always show it from the left. It has also been suggested that Brancusi incorporated, consciously or otherwise, his own vigorous desire for the female form into his representation.

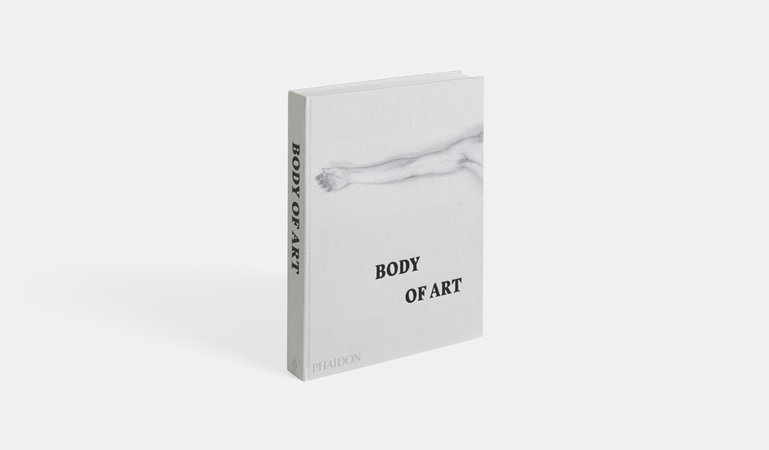

UNTITLED

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore

1921–2

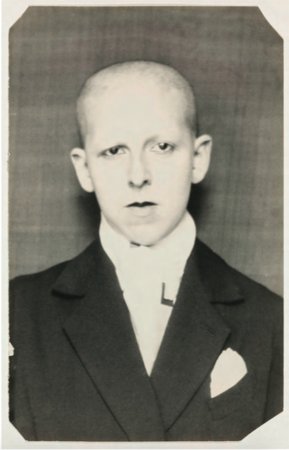

Artistic collaborators, lovers, stepsisters, and French Resistance fighters, Claude Cahun (1854–1954) and Marcel Moore (1892–1972) created works that investigated gender and identity politics in Europe between the wars. Born Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe respectively, the women adopted male pseudonyms. Cahun, who began experimenting with self-portraiture in 1911, is the subject of most of their photographs, which were never exhibited during their lifetimes and only came to light in the 1980s. These performative portraits explore the fluidity of gender. In some Cahun is hyper-feminine in exaggerated make-up and kiss curls, while in others she is hyper-masculine in a sailor suit or with a shaved head (something extremely rare for a woman in the 1920s) and a dandy’s evening finery. Here, Cahun, wearing a cravat and velvet jacket with a pocket-handkerchief looks out at the viewer with a defiant expression. She was interested in upending conventional notions of gender not only in her dress and her art but also her writing. When translating Havelock Ellis’s groundbreaking texts on gender and transgender identity she asserted: “Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neutral is the only gender that always suits me.”

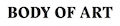

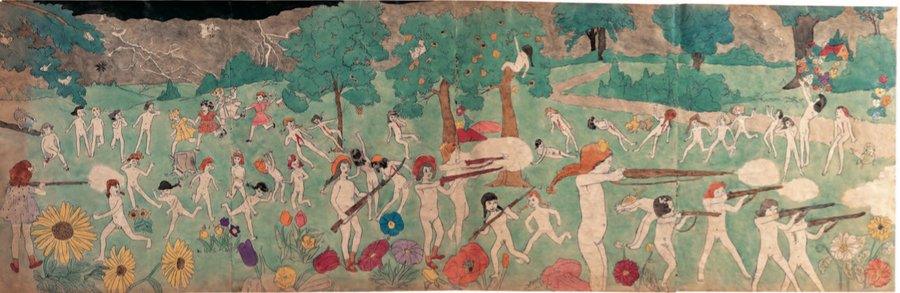

UNTITLED (DOUBLE-SIDED), ILLUSTRATION FOR

IN THE REALMS OF THE UNREAL

Henry Darger

Mid-20th Century

When Henry Darger (1892–1973) died in 1973 he left behind a lifetime of work in his one-bedroom Chicago apartment. Darger, who had worked as a janitor in a hospital for most of his adult life, was a man immersed in his own radical imagination. In isolation he labored at a 5,000-page manuscript titled The History of My Life ; kept a journal that fastidiously tracked weather conditions over a ten-year period; and, most significantly, created a fantastical 15,145-page illustrated tale, In the Realms of the Unreal . The heroines of this epic story are the Vivian Girls – seven child princesses and sisters fighting in a conflict that was inspired, in part, by news reports, the American Civil War and Darger’s personal life. The girls’ evil enemies, the Glandelinians, are adults who enslave, gruesomely torture, and massacre children. Darger, who had suffered a traumatic childhood, wrote himself into the story as the children’s protector. Subject to many interpretations and much debate is his depiction of children as transgendered, often showing young girls naked with prepubescent penises. Blending watercolor, magazine cutouts, Catholic references, and other imagery, his pictures can be both disturbing and magnificently lyrical. Preceding late-twentieth century movements such as Pop art but at the same time defying categories, Darger’s art is brimming with vibrant obsessions and imaginative totality.

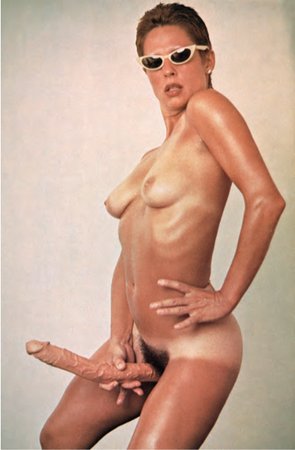

UNTITLED

Lynda Benglis

1974

Better known for her large-scale, post-Minimalist sculptures of poured polyurethane foam, Lynda Benglis (b.1941) also created a series of photographs parodying stereotypical gender roles, such as this work, photographed by Arthur Gordon, in which she poses as a tanned and oiled pin-up. Such an image might normally feed a consuming heterosexual male gaze, but Benglis intervenes by holding an outsized dildo as if it were her penis. The dildo, like her large-scale sculptures, challenged the implicit male chauvinism of the contemporary art world by mocking symbols of male power. Benglis said of the then-dominant Abstract Expressionist movement, “I saw it was a big, macho game, a big, heroic Abstract Expressionist, macho, sexist game. It’s all about territory. How big?” Part of that territory included the commercial infrastructure of art (such as galleries and trade magazines) to which she ultimately draws attention in this work. Benglis tried publishing this photograph in Artforum as an “artist’s statement”, but the editor refused. So instead she and the Paula Cooper Gallery purchased advertising space in the magazine. The provocative double-page spread advert consisted of her bold photograph and a page and a third of stark black with the gallery’s name inconspicuously printed in the upper left.

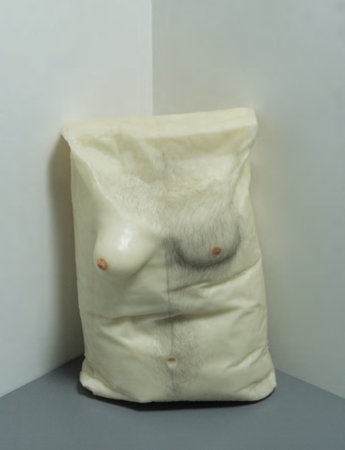

UNTITLED

Robert Gober

1991

Slumped on the gallery floor as though abandoned, this sculpture has the initial appearance of a heavy sack. It also bears the identifying marks of the human body, both female and male: a breast on one side, a man’s hairy pectoral on the other. Gober’s (b.1954) untitled sculpture operates on the fault line between the real and the illusory. Here, he has created a beeswax torso the color of pale flesh, cast in a real bag, with real human hair that seems to sprout naturalistically. Limbless and headless, it resembles a classical torso displayed in a museum, a fragment of its former self. Yet by aligning the gravitational pull of the wax cast and the signifiers of the human body, Gober’s work acquires a poignant sense of frailty far from the classical ideal. Much of the artist’s work was made in the context of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 90s, and his images of abandoned, weakened bodies’ take on additional pathos in this light. By depicting the torso as hermaphrodite, Gober suggests the fluidity of gender categories. Sidestepping attempts to categorize the body as either male or female, the work occupies an awkward spot, both in the room and in assumptions about bodies in general.

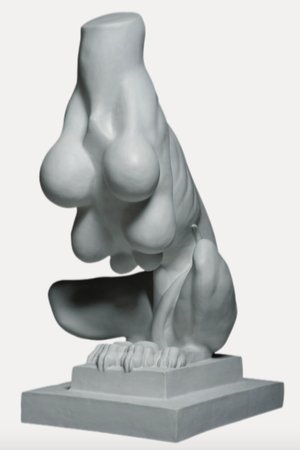

NATURE STUDY

Louise Bourgeois

1996

Crouching on a plinth is a headless, dog-like creature with a human back and multiple protruding breasts. Its sharp claws and muscular physique suggest power and aggression, yet its smooth, hair- less surface bestows a sense of vulnerability. Not only is this strange beast part-animal and part- human, but it is also part male and part female, as indicated by the conspicuous phallus between its splayed hind legs. Bourgeois’ sculpture was inspired by an eighteenth-century marble in the Louvre by F.A. Franzoni (

Trone of a Priestess of Ceres

), in which two winged sphinxes sit guarding a throne. Doing away with the head, arms and wings, Bourgeois (1911–2010) draws attention

to the ambiguous sexuality of her creature, which she claimed was a symbolic self-portrait. The six breasts represent her nurturing role as a mother and wife, providing for her husband and three sons. While the claws symbolize the defensive matriarch, guarding those she loves, Bourgeois described the phallus as "the subject of my tender- ness ... after all, I lived with four men ... I was the protector." Although the work is highly personal to the artist, its themes of desire, sexuality, nurturing and protection are universal.