What is Pop art? More than just popular art. “Once you 'got' Pop, you could never see a sign again the same way again,” Andy Warholonce said, “and once you thought Pop, you could never see America the same way again.”

Or just listen to Roy Lichtenstein’s take: "Pop Art looks out into the world. It doesn't look like a painting of something, it looks like the thing itself."

But while those American masters seem synonymous with any definition of Pop art, it all actually began in London. The term Pop art came into use in the 1950s during discussions led by the artist collective known as the Independent Group at London's Institute of Contemporary Arts. One of those artists in the Independent was Richard Hamilton, widely considered the first Pop artist, and his own definition of the term was disjointed: "Popular (designed for a mass audience); Transient (short term solution); Expendable (easily forgotten); Low Cost; Mass Produced; Young (aimed at Youth); Witty; Sexy; Gimmicky; Glamorous; and Big Business."

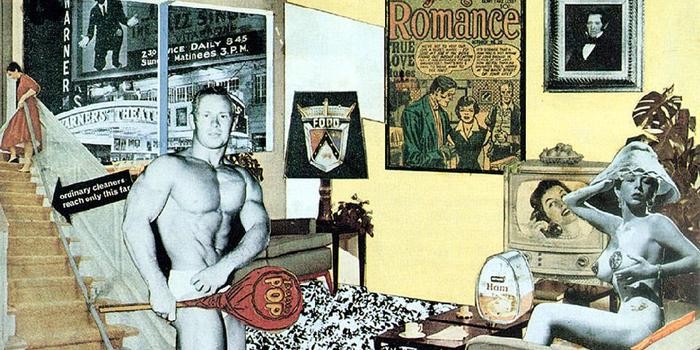

Hamilton is often credited with creating the first piece of Pop with the collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Home So Different, So Appealing? (1956), in which glamorous cutouts of a man and woman play house in a domestic dreamland filled with consumer goods. Front and center, gripped in the man’s hand, is a bright red Tootsie Pop—the latter word literally “popping” out of the frame.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., artists in the mid-1950s began to create a bridge to Pop. Strongly influenced by Dada and its emphasis on appropriation and everyday objects, artists increasingly worked with collage, consumer products, and a healthy dose of irony. Jasper Johns reimagined iconic imagery like the American flag; Robert Rauschenberg employed silk-screen printings and found objects; and Larry Rivers used images of mass-produced goods. All three are considered American forerunners of Pop. “Larry’s painting style was unique—it wasn’t Abstract Expressionism and it wasn’t Pop, it fell into the period in between,” Warhol once said of Rivers.

But it was not until the 1960s that Pop art truly exploded onto the American art scene with "The New Realists” show at Sidney Janis Gallery in New York in 1962. The Americans in that show included Warhol alongside Jim Dine, Robert Indiana, Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, George Segal.

Warhol’s revolutionary Factory would go on to redefine the art of an era, casting new light on ideas about mass production, fame, and the artist’s public persona. Warhol’s Factory churned out assembly-line silk-screens while musicians, actors, and writers hung around in a smoke-filled narcotic haze. His prints of celebrities ranging from Marilyn Monroe to Elvis are some of the most recognizable artworks of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, Lichtenstein began to use Ben-Day dots and imagery from comic books to create alternately saccharine and histrionic panels. Oldenburg dealt in everyday objects, blowing up hamburgers to abnormal size and showcasing sculptures of comfort foods, while Rosenquist took his background as a billboard painter to imagine glamorous, surrealistic mash-ups of candy-colored cars, smiling faces, or advertisements. On the West Coast, Ed Ruscha conceived deadpan, textual canvases. Pop art represented a rejection of Abstraction Expressionism in favor of a complete embrace of the consumerism, popular culture, and ironic whimsy that had begun to define postwar America.

Pop art didn’t end with the 1960s though. Born in 1958, Keith Haring, too, is considered a seminal Pop artist, though his work did not appear until the late 1970s and early '80s. His murals drew heavily on the breakthroughs of his predecessors, and his flat, cartoonish forms—often filled with political and social commentary—helped pave the way for yet another popular art form: street art.

And the genre continues to thrive today. Japanese artists Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara serve as key examples of the contemporary Pop artist. Murakami coined the term “Superflat” to define his work, which makes use of cutesy, pop-culture motifs like smiling flowers and skulls, often to satirical effect. His famed collaboration with Louis Vuitton, in which his Superflat floral imagery appeared on luxury handbags, perhaps confirmed Warhol premonitions that art and consumer culture would increasingly become intertwined. “Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art," he said. More than a few artists today might agree.