The fact that New York, London, and Paris have such rich and robust art scenes make them some of the best places in the world to visit (and live in). But working within such established and historical art cities can make it hard to see outside of the "box." Perhaps this is part of the reason why so-called "peripheral" cities in places like Nigeria, Romania, and Lebanon have exploding avant-garde art scenes full of artists and curators who are experimenting in ways that might feel too risky in better-known cities where the stakes (and rents) are higher.

Excerpted from Phaidon's Art Cities of the Future: 21st Century Avant Gardes , we've highlighted three global cities with thriving experimental art scenes, along with one outstanding artist per city who has helped put their hometown on the map.

LAGOS, NIGERIA

Perhaps unsurprising given its population of more than fifteen million, today Lagos has the largest local art scene in West Africa, bolstered by more than twenty art and cultural institutions, a sizable local collector base, a strong art market and a profusion of artists working across a range of media. Like the ever-evolving city itself, the art scene is at times difficult to grasp, not simply because of its density, but also due to its multi-directionality.

In 1983, Dr. (Chief) Newton Chuka Jibonoh established the Didi Museum, the country’s first private non-profit art institution. With the imperative to preserve and display Nigeria’s artistic heritage, the museum became notable for exhibiting vanguard Nigerian Modernist painters such as Yusuf Grillo, Bruce Onobrakpeya and Ben Enwonwu as well as traditional bronze works from Benin and Ile-Ife.

Over the past two decades, alternative spaces have proliferated in regional cities such as Accra, Contonou, Dakar and Douala, so it comes as no surprise that such institutions have led the way for cultural and artistic expression in Lagos. In this regard, 2007 was a watershed year for the city’s contemporary art scene, when independent curator Bisi Silva founded the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (CCA), which currently consists of a gallery, a residency and the largest art library in West Africa. Beginning with “Democrazy” (2007-08), a trilogy of politically-charged exhibitions chronicling Nigeria’s recent history and the subsequent impact on art and culture, CCA has continued to show challenging and experimental artwork by Nigerian and international artists. The controversial exhibition “Like a Virgin” (2009), featuring work by Nigerian artist Lucy Azubike and South African artist

Zanele Muholi

, broached issues surrounding gender, sexuality and lesbianism in ways previously unexplored locally, eliciting heated debate in the city’s often-conservative art community.

Andrew Esiebo, Untitled from the series "Wo We Are" (2010). Esiebo's practice broaches issues of sexuality and masculinity that few of his Lagos contemporaries have attempted.

Andrew Esiebo, Untitled from the series "Wo We Are" (2010). Esiebo's practice broaches issues of sexuality and masculinity that few of his Lagos contemporaries have attempted.

Beyond institutions, surges of artist initiatives have promoted ideas of civic exchange among the city’s diverse population. In 2011, artists Richardson Ovbiebo, Victoria Udondian and six others collaborated on A Kilo of Hope , a five-day residency at a landfill in the Lagos suburb Oke-Afa, Isola, which engaged the community in re-commodifying refuse materials. Such projects disclose a key reality of the city’s art scene: through greatly diverting in concept, style and media, a strong sense of fellowship and a mutual interest in contemporary art’s critical possibilities are points of cohesion for Lagosian artists.

This fellowship is most pronounced in recent artist collectives, especially in photography, which has gained prominence due to its critical potential and portability. In 2001, the Depth of Field collective (DOF) began to elaborate on the work of pioneering photographers J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Don Barber and Sunmi Smart-Cole by remaining the cultural life and social realities of the city. During the intense political period following Nigeria’s reinstated democracy, the six members of DOF met weekly to exchange ideas and devise means of dementing city transformations.

There are many other independent projects and artist-led initiatives that have emerged in recent decades, which still demand rigorous examination. However, the aforementioned developments are noteworthy for the ways in which they foreground the city as a living entity, entertain the complexities of contemporary life and exemplify the enterprising and resourceful spirit characteristic of Lagos and its inhabitants. The growing international buzz surrounding ambitious local institutions and artist-led projects suggest that this port city will be a vital capital for contemporary art and culture in the twenty-first century.

Lagosian Artist to Know: JELILI ATIKU

Jelili Atiku performing Eleniyan (In The Red Series #13), 2012, Lagos

Jelili Atiku performing Eleniyan (In The Red Series #13), 2012, Lagos

An activist whose practices is premised on the advocacy of human rights and the promotion of social justice, over the years Jelili Atiku has dedicated his art to raising social consciousness. Although working in sculpture, drawing and video, it is primarily his performance art—a medium underrepresented locally—that has positioned him at the forefront of contemporary art in Lagos. Among his most ambitious endeavors is In the Red (2008-present). Taking place on the streets or within institutional contexts in cities such as Lagos, Contonou, Lomé Kampala, Harare, Tokyo and London, this project derives its title from Atiku's attire: a head-to-toe bodysuit wrapped with dangling red bandages. While, for the artist, the color alludes to life and death, vitality and mummification, the costume and the spontaneity of his performances are generally inspired by both the political activism of an artist like Joseph Beuys and Yoruba Egungun masquerade traditions which commemorate the dead through ancestral worship. Atiku typically presents himself as a spectacle—suspended by rope from the side of a building, disrupting the flow of overcrowded streets or posing as a public monument—in order to stimulate awareness of global or place-specific political issues.

CLUJ-NAPOCA, ROMAINIA

There was a time when, if you had declared Cluj a contender to become an internationally regarded center for contemporary art, people may have raised an eyebrow. Yet Cluj has succeeded in coming to the attention of the art world, and its artists have managed a feat that ten years ago would have seemed like a fulfillment of a dream.

Cluj is not the capital of Romania. This might initially seem a hindrance rather than a positive factor for the city’s creatives. Yet for several reasons this fact seems to have worked in its artists favor. Home to Romania’s largest university, Babes-Bolyai, Cluj has a thriving student population of around 49,000, numbering almost a sixth of the 309,000 people who live within the inner city. The proportionally high number of students contributes greatly to the urban vibrancy. Compared to established art capitals such as London, Paris and New York, Cluj is an inexpensive place to live and work, and it offers a good standard of living even for emerging artists.

As the current generation of Cluj artists were growing up, they knew—even at a subconscious level—that it would be much more difficult for them to achieve national recognition and success than their Bucharest counterparts. They felt they would always battle with the ‘provincial’ label. They saw the necessity of fostering a thriving community of artists in Cluj, and this was coupled with the understanding that to achieve fame and recognition they would first have to break into the international art market and receive validation that the Bucharest’s art tastemakers could not ignore.

Rather than describing Cluj as home to a homogenous group of artists, however, it would be more accurate to describe it as host to a number of different circles. Recent comments on ARTINFO.com and in the Financial Times have mentioned the ‘Cluj School’ and the ‘Cluj Scene.’ Thematically too, the artists share an interest in historical events from the last century, which they express from a distanced watchful perspective.

The Fabrica de Pensule (Paintbrush Factory) opened in the autumn of 2009. Together with Mihai Pop, one of the co-founders of Plan B Gallery, and a number of other artists and creative, the Paintbrush Factory was transformed into a centre for the arts, with artist’s studios, workshops and galleries on site including Plan B, Bazis and Sabot.

As the first successful gallery to foster, sustain and promote Cluj’s young artists on the home front, Plan B provided an inspiring model of other Romanian galleries. It opened with a solo exhibition of Victor Man’s work in 2005, which marked the first time an American art magazine, Art in America , covered a commercial Romanian show.

Victor Man,

Ubiquitous you

, 2008.

Victor Man,

Ubiquitous you

, 2008.

Recognition of the significant role of the “curator-gallerist” on the national and international stage has made itself manifest in relation to several Cluj galleries and international events. The activities of Attila Tordai-S have been key in promoting critical approaches to the market. Tordai-S is a former editor of the influential

IDEA arts + society

magazine, which maintains an important international network and covers the shows of many Cluj artists both at home and abroad.

Cluj Artist to Know: ADRIAN GHENIE

Adrian Ghenie,

Self Portrait as Charles Darwin

, 2011

Adrian Ghenie,

Self Portrait as Charles Darwin

, 2011

Adrian Ghenie’s career to date has been stellar. It’s trajectory—marked by his emergence on the international art scene in Haunch of Venison’s group show ‘Cluj Connection’ in Zurich in 2006 to his current position as one of the most respected young artists in the world—is perhaps the steepest of all the Cluj artist. Often described as the ‘history painting,’ Ghenie creates powerfully arresting works that demonstrate his fascination with the twentieth century. Man of his most important paintings address humiliation through the depiction of slapstick.

Adrian Ghenie's

Study for the Devil Three

, 2010 is available here on Artspace

Adrian Ghenie's

Study for the Devil Three

, 2010 is available here on Artspace

BEIRUT, LEBANON

Like other cities in the region, Beirut considers its contemporary art scene to have begun in the 1990s rather than the 1970s. Looking at the city in isolation, it’s tempting to see this as a logical consequence of Lebanon’s fifteen-year civil war coming to an end in or around 1990; that cultural production was horribly interrupted during the war years and then bravely resumed during the reconstruction era would make sense. But this isn’t true. On the one hand, artists and their ilk continued to work throughout the conflict. On the other hand, Beirut never regained its prewar stature; it never returned to its golden age. What was lost during the war was lost for good. And yet, on the level of artistic infrastructure, Beirut shares many attributes with cities such as Cairo and Istanbul, both of which have had their problems, though neither has ever collapse so completely into violence.

Beirut inspired the style, verve and literary toughness of Don DeLillo (in Mao II ) and J. G Ballard (in the short story War Fever ). Both writers stuck to the relatively safe terrain of the city’s renowned chaos, digging up an important truth that is well known but rarely stated: Beirut is totally and utterly obsessed with itself. Perhaps for this reason, the city exerts an incredible weight on the artwork its residents have produced, particularly on the experimental end of the spectrum, where the material of the city has become at once medium, metaphor and generator of meaning.

Besides an interest in modernist ruins, very little remains to connect the artistic experiments of post-war and prewar Beirut. Three women provide the exception. Nadine Begdache is the only gallerist in town with roots in the 1960s. In 1993 she opened Galerie Janine Rubeiz, named in tribute to her mother, who was the force behind the cultural center Dar al-Fan, which opened in 1967 and staged legendary exhibitions alongside contentious encounters among literary, artistic, religious and political figures.

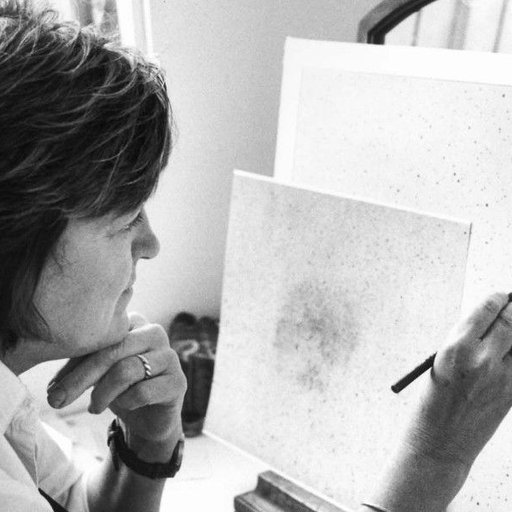

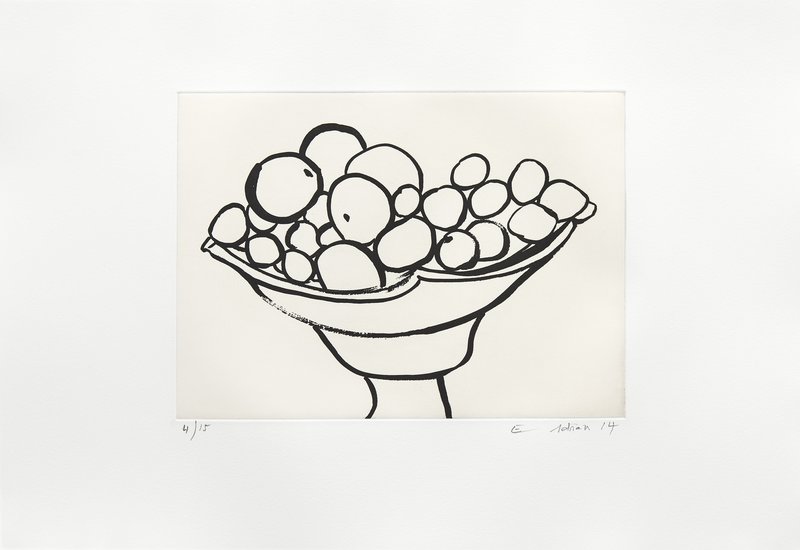

One of the artists who showed with Dar al-Fan was Etel Adnan . The author of one of the most important wartime novels, Sitt Marie Rose —about a woman kidnapped by militiamen and killed for her commitment to the Palestinian cause—Adnan’s boundless love for Beirut is perfectly counterbalanced by her ruthless criticism of the place. “What saves you from despair in Beirut is the very difficulty of living in it,” she writes in Of Cities and Women: Letters to Fawwaz. Now in her eighties, Adnan is beginning to earn the international recognition she deserves, as is her colleague Saloua Raouda Choucair, a sculptor in her nineties whose approach to abstraction makes her the Lygia Pape of Lebanon.

Etel Adnan's

Compotier III

, 2014 is available here on Artspace

Etel Adnan's

Compotier III

, 2014 is available here on Artspace

That these two great but for decades overlooked artists are finally being honored at home and abroad is directly due to the work of commercial galleries such as Andrée Sfeir-Semler, who, in 2005, opened Beirut’s first blue-chip gallery for international contemporary art with a strong minimalist and conceptual bent, and Saleh Barakat, who established the Agial Art Gallery in 1990, and whose affinities lie more firmly with modernism, or the one hundred years before the contemporary began in Beirut.

But the newfound attention to Adnan and Choucair is also indirectly due to the work of a generation that began building a nimble, flexible and wholly independent infrastructure for the production, presentation and dissemination of a new and often challenging work in the early mid-1990s. Ashkal Alwan (the Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts) was founded in 1994, helped to initiate what the artist Walid Sadek has described as “a search for places” in the post-war period. Young and fearless artists with no hope or desire for commercial interest in their work began making art for the purpose of either reconfiguring “the once-embattled terrain” of the city, or for claiming some measure of responsibility for the preceding years of violence.

Around the same time, the photographers Fouad Elkoury and Samer Mohdad started the Arab Image Foundation with a young video artist named Akram Zaatari. Since 1997, the Arab Image Foundation has gathered together more than five hundred thousand photographs and related materials. The composition of the collection was driven entirely by artists and the foundation soon attracted the collaboration of Walid Raad , Jalal Toufic, Lamia Joreige and many others.

In 2002, Ashkal Alwan began organizing the very open and very public Home Works Forum for Cultural Practices—the closest thing Beirut has to an international biennial, though in many ways better. Home Works happens roughly every few years, or whenever the situation in the city, the country and the wider region allows. After another war in 2006, Ashkal Alwan created Video Works, a production program for young and emerging artist to test out ideas in a context that has become familiar: the need, desire, obsession or folly to respond to current events as they are unfolding, in art.

By 2012 Beirut had more commercial and non-commercial art spaces than ever before. What’s more while the scene may still be factional—and sometimes insidiously reflective of Lebanon’s sad, sectarian political system—it has come to accommodate generations of practitioners who rebel, betray and rediscover one another. Many contemporary artists have had their curiosity sparked by the modernists who came before them. As Samir Kassir, the city’s most probing historian, who was killed in a car bomb blast in 2005 wrote, “For Beirut stands out among the cities of its age not only for having helped to formulate the history of Arab modernity, but also, and still more importantly, for having helped make it a living thing—even if, in doing so, Beirut lured itself into a dead end.”

Beiruti Artist to Know: AKRAM ZAATARI

Installation view of Akram Zaatari's

The End of Time

, 2012 at Documenta 13

Installation view of Akram Zaatari's

The End of Time

, 2012 at Documenta 13

These days Zaatari is regarded as one of the most important artists of his generation, not only in Lebanon but also amongst foremost practitioners playing with the meaning of photography, the potential of video and research-based practices. The End of Time (2012) is a silent, black-and-white 16mm film that gracefully twines together the two disparate strands that have run through Akram Zaatari's practice for nearly twenty years. He describes the piece as "a choreography for two lovers, enacted by three figures." In each of the film's three parts, three young men rotate through two roles in which they repeat the same sequence of gestures; they embrace, one staggers and falls, they remove their clothes and then one pushes the other away. Only the third section is punctuated by intertitles explaining the actions as a game of truth or dare. The dare is to fall in love. At the end of an affair, a romance, a relationship, or time itself, the lover tells his beloved that he is leaving. We see a leather satchel, a hard drive box, a box of pictures and a pile of neatly folded clothes. With this final gesture—in a fim that is part of a larger time-capsule project that literally buried some effects of teh Arab Image Foundation in the ground near the Fulda River in Kassel for Documenta 13—Zaatari likens a long history of archival practice to failure, heartbreak and emotional collapse.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Three Exhibitions That Changed Global History