During the Q&A portion of Chris Kraus 's After Kathy Acker reading at CUNY earlier this year, two young protestors took to the mic to express their concerns about the author's decision to participate in a reading at 365 Mission , a gallery in Boyle Heights , Los Angeles, despite tensions regarding the neighborhood's new gallery row and its role in displacing longstanding residents. Kraus's publishers later announced that the L.A. reading would be cancelled, citing threats from anti-gentrification activists in Boyle Heights who promised to disrupt the event. The author refused to comment on the protestor's concerns, simply stating that the release of her new biography was not the place to discuss such issues. But could an event such as this reading be the exact time and place to address the topic of art's role in the displacement of communities? Do artists and art spaces have a responsibility to examine the effect on the spaces they inhabit?

To give you a bit of background info: Boyle Heights is a predominantly working class Hispanic neighborhood situated east of L.A.'s Arts District. Residents fear that the influx of gallery spaces in their neighborhood will lead to their displacement and ultimate cultural erasure. Members of the Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement ( BHAAAD ) are demanding that art galleries in Boyle Heights relocate to other, more affluent areas of the city. It's not that Boyle Heights residents just don't like art; rather their efforts proactively address the historically damaging effects that art spaces can have on a community's deep-rooted residents. When developers see a neighborhood flourishing with art galleries and bougie cafes, they see a potential for exorbitant profit. Maga Miranda , a protestor affiliated with BHAAAD, told L.A. Weekly that "we’re not against art or culture... the Eastside has been an incredibly active place when it comes to art and culture. But the art galleries are part of a broader effort by planners and politicians and developers who want to artwash gentrification."

If Boyle Heights needed any proof of the link between developing arts communities and gentrification of working class neighborhoods, they need look no further than New York City. NYC's Chinatown has seen more than 60 galleries established in the past three years. The Chinatown Art Brigade writes that "rents have risen to an all time high and low-income Chinatown tenants and small business owners are being pushed out. Hyper-development—in the form of luxury condos, hotels and galleries—is putting the lives and livelihoods of long-term residents at risk." The group acknowledges that gentrification is the result of a number of factors, however "as evidenced in SoHo, Chelsea and, more recently, Bushwick, art galleries tend to be among the first businesses to gentrify working class or industrial districts." They are forced to ask the question "what, if any, are the points of unity between artists, galleries and the local community?"

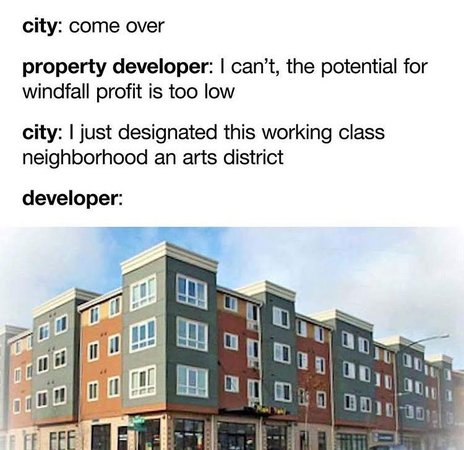

Has "arts district" become a fancy way of saying "displacement"? For those living in these districts, the opening of an art gallery can feel less like a celebration and more like cause for concern over the potential for property values to skyrocket, and as more affluent investors and residents move in, the need for longstanding residents to relocate, despite having, in many cases, lived there for generations. You may have seen this meme floating around the internet, which sums up the process rather concisely.

When artists and galleries move into what is branded as a "newly established art community," they generally don't think of themselves as gentrifiers so much as they think of themselves as pioneers of a "new community," (as opposed to new members of the pre-existing, already culturally-rich community). So it's not just that these art galleries attract developers like ants to a picnic; it's also that they often display a blatant disregard for the rich history of the community they are overtaking.

But what if artists and art spaces acknowledged their role in the displacement of communities, and worked proactively to counter the 'artwashing' of communities? Could they reverse the efforts of developers, and rather help a pre-existing community to thrive?

We spoke to Eileen Isagon Skyers , creative director of Bed-Stuy gallery HOUSING, whose goal is to de-gentrify the gallery space and foster support for local, long-standing businesses in the neighborhood. HOUSING is co-run by Skyers and gallery director/owner KJ Freeman , and is located at 424 Gates Ave., a space formerly occupied by gallery American Medium , who moved to a new location near David Zwirner in Chelsea back in September. Skyers tells Artspace that "since its inception, the plan has been to create an inclusive space, dedicated to the work of artists and creatives of color."

HOUSING, Image Courtesy of the gallery's website

HOUSING, Image Courtesy of the gallery's website

Freeman and Skyers are highly aware of the area they are inhabiting, and are sensitive to preserving its rich cultural history. Says Skyers, "artwashing is a part of this whole... anxiety that demographic changes in a neighborhood cue an imminent hike in rent and displacement—a process that disproportionately affects women of color. Remaining conscious of this, and participating in its undoing in a small way, is the least that art spaces can do. We're not here to engage in 'urban renewal', or promote narrow notions of 'community.' We live here, and we are in love with the neighborhood exactly as it is. While we don't know how much we can truly counter some of these insurmountable issues, we still want to do our part: raising attention, exhibiting works that might resonate with people in the neighborhood, and urging others to support local businesses that have operated in the area well before it was 'up and coming.'"

She goes on to say that "Art is, in many cases, much better at exposing society's intricacies and contradictions than it is at intervening or mitigating them. Artists may inherently react, or respond, to our time in history in one way or another, but this doesn't imply that we are expected to be activists or social justice warriors. I think this is precisely what allows room for more freely executed expressions, and provocations to occur."

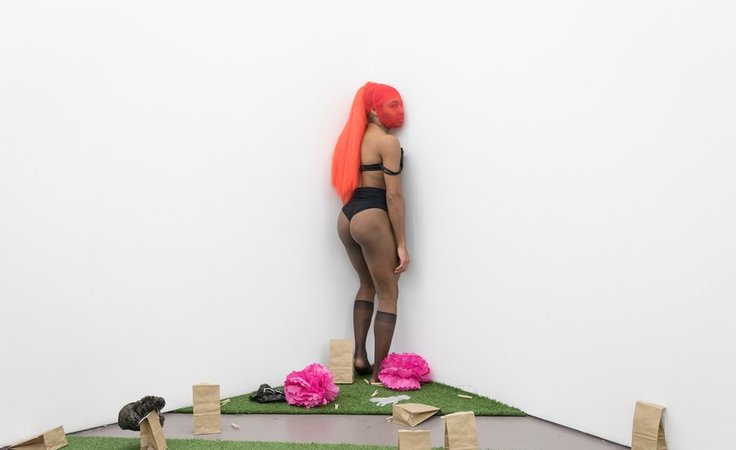

Keijaun Thomas performing "Black Angels in the Infield: Dripping Faggot Sweat" at HOUSING.

Keijaun Thomas performing "Black Angels in the Infield: Dripping Faggot Sweat" at HOUSING.

HOUSING's approach to curation is to exhibit distinct voices, and to offer their space as a place for the neighborhood to come together and engage in conversation. A major part of their efforts are about keeping their doors open to the neighborhood, offering events such as "figure drawing sessions and artists talks that are more like loosely organized conversations between friends. In no way does a close resonating with this work depend on having a precise theoretical background." Artists are not chosen based on their credentials, but rather on their ability to incite a dialogue. Says Skyers, "KJ curated a majority of this exhibition season by connecting with friends like Cheyenne Julien , Parker Bright , and Brandon Drew-Holmes , among others—artists who are challenging the record of art world white supremacy, or addressing environmental racism, and who we are incredibly fortunate to have worked with right out of the gate." (If you want to get a taste for HOUSING's offerings, the closing performance of Keijaun Thomas 's Black Angels in the Infield: Dripping Faggot Sweat, is on December 6 at 7pm, and the opening event for RAFiA Santana's solo exhibition on December 16th at 6pm.)

Richard Beavers Gallery, also a gallery in Bed-Stuy Brooklyn, operates under similar sentiments as HOUSING. Established in 2007, the gallery shows and collects artists whose work depicts urban life and the rich culture of New York's longstanding neighborhoods while also addressing the numerous political and social issues present in these communities today. The goal of the space is "to educate, inspire, and stir consciousness—whether you are a seasoned collector, art appreciator or merely have an interest in art." The galleries upcoming exhibition, opening on December 16, is Frank Morrison 's Urban Restoration. Says Morrison, "my work dignifies the evolution of everyday, underrepresented people and places within the urban landscape. I seek to both highlight and preserve the soul of the city through the lens of hip-hop culture and urban iconography. The rhythmic gesture and movement within my work balances the often gritty and decayed surfaces with vibrancy and authenticity."

Richard Beavers Gallery, Image courtesy of the gallery's website

Richard Beavers Gallery, Image courtesy of the gallery's website

In Bushwick, one of New York's most rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods, a collective of New York-native artists are fighting back by shedding light on the issue, literally. Activist art group Mi Casa No Es Su Casa , based out of Mayday Space in Bushwick teamed up with NYC Light Brigade to conduct a project called Illumination Against Gentrification . The group constructs neon signs, which say things like "Gentrification is the New Colonialism", "Not For Sale", "No Me Desplaces", "Decolonize the Hood", "3 Generation Household", and "No Eviction Zone". These signs are placed in small local business and homes all over NYC: including Bushwick, Crown Heights, Corona, Jackson Heights, the South Bronx, Harlem, Inwood, Jackson Heights, and more. The group seeks to raise awareness about the struggles of those who are vulnerable to the forces of gentrification and displacement, and the onslaught of discrimination and harassment that often comes along with it.

"Gentrification is the New Colonialism," by Mi Casa No Es Su Casa, Image courtesy of Pinterest

"Gentrification is the New Colonialism," by Mi Casa No Es Su Casa, Image courtesy of Pinterest

The existence of these activist groups and spaces who are using art to build a visible resistance give us hope that there is a world in which fostering art and expression within a community does not inherently lead to the displacement of its core residents and businesses. For this to work, art communities and artists would need to accept responsibility for the effects of their practice, and proactively work to be more inclusive and respectful of the spaces and cultural histories they are entering. The most important thing is to keep the dialogue going. We've learned from experience that art and gentrification get along like two peas in a pod, and therefore wherever there is a conversation about art, there is room for a dialogue about its potential to displace others. The least we can do is listen.