Pablo Picasso’s prolonged engagement with paper was to be the subject of a groundbreaking exhibition Picasso and Paper, organized by the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in collaboration with the Musée national Picasso-Paris next month.

Featuring nearly 300 works spanning the artist’s entire career, Picasso and Paper would have offered new insights into Picasso’s creative spirit and working methods. Nowhere is Picasso’s protean spirit more evident than in his relentless exploration of working on and with paper.

In this edition of our 'Anatomy of An Artwork' column, a series in which we spotlight a single piece of art from a major forthcoming exhibition - and we'll be keeping up with the series while lockdown continues - Torey Akers does a deep dive on "Women at Their Toilette", a Picasso masterwork. When you've read it, check out our Artspace-exclusive gallery of this legendary artist’s work, available to buy now.

Everyone’s mom is the most beautiful woman on earth, and mine is no exception. As a kid, I was fascinated by the meticulous process she underwent to enter the night-world of grown-ups, one that involved clinking glasses and loud laughs and no kids, an exclusion that made her transformation all the more bewitching. The grinding whirr of a side-zipped skirt, a careful slick of mascara, her focused, furrowed brow weighing necklace options in the mirror—all coalesced into a preparatory mosaic of glamour I found hypnotic.

Mary Cassatt, "Mary at the Bath", 1891, via Wikimedia Commons

The ritual of feminine performance is a necessarily intimate one, charged with social expectation and the achingly personal moments undergirding collective womanhood. It’s useful, then, to consider the art historical trope of the “La Toilette”, a painterly motif involving women getting dressed or undressed to bathe or groom, not merely as a scopophilic endeavor, but a larger project of cultural voyeurism, a longing, ginger glance at modesty’s tremulous underbelly. This objectification of female interiority is as much a form of civic reflection as it is a point of indulgence, a balance reminiscent of its subject’s titillating and oft-scorned duality. Perhaps that’s why the “La Toilette” motif has proven so enduring; its attributes invite a multi-valent gaze, poetically total in its liquidity. Women of all stripes—rich, poor, decent, daring, artist’s models and beautiful moms alike—have readied themselves beneath the convex lens of art history, vulnerable, self-possessed, and elegantly exposed under a painter’s, or viewer’s, watchful eye.

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec "La Toilette" 1889, via Google Project

The evolution of women’s hygiene conventions, and the way artists portrayed those conventions, tells the interlacing tale of class and privacy, the latter a relatively recent invention in the Western world. The “La Toilette” metonymy was popularized by the French, who had fewer hang-ups concerning nude depictions neither biblical nor mythological in nature (the English, by contrast, stuck to a binaristic “ladies and whores” model until the late 18th century). During the Renaissance, the act of “la toilette” denoted nobility; only gentry and royalty would have the privilege of taking a bath in cold water, soap-free, doused in perfumes, salves and herbs, which were then believed to be cleaning agents.

Georges de La Tour, 1638, "Woman Catching Flea" via Musee Lorrain

Georges de La Tour, 1638, "Woman Catching Flea" via Musee Lorrain

For everyone else, baths were a twice-yearly treat, and an expensive one at that. Plus, the danger of catching cold or disease made the very thought of a bath unduly dangerous, which relegated regular water usage to genitals, hands and feet. Rich women were rarely alone, requiring attendants to get dressed, a testament to their value as highly-surveilled property assets and creatures of the utmost delicacy. If a woman was pictured solo in her hygiene preparations, viewers could necessarily extrapolate a background in service or sex work. It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that people in urban areas stopped renting bathtubs, which had to be lugged from door to door, a chilling tidbit that tracks with the proliferations of pictures involving beautiful young women picking fleas and vermin off of their persons.

"The Bath", a tapestry depicting manorial life from the Southern Netherlands, c. 1500

The largely male patronage of these pieces led to some surprisingly randy perversions of the concept - Francois Boucher’s “La Toilette intime” shows its subject urinating in a billowing hoopskirt, speaks to fetishistic obsession with visual access (the image is painted on the back of a portrait of the same woman playing with her dog). However, as water became more available, so too did indoor plumbing, and artistic mores shifted towards a lived-in, experiential hand. By 1870, women were expected to take solitary baths, and the role of the male artist’s gaze felt less panoptical than quietly yearning, acknowledging the untouchable, meditative silence of his chosen milieu. It seems fitting that the most tender “la toilette” iterations of this period were made by women, whose sweet, quiet deployment of documentary identification captured the cryptic dynamics at play.

Shona McAndrew, "Cheyenne", 2019, via CHART Gallery

Shona McAndrew, "Cheyenne", 2019, via CHART Gallery

Contemporary updates of “la toilette” invariably focus on the sitter’s inner life, a welcome turn away from Bonnard’s peeping tom or Toulouse-Lautrec’s trailing stare. Artists like Shona McAndrew and Shannon Cartier Lucy take explicitly millennial and tacitly feminist approaches to domestic intimacy, investigating beauty, selfhood, and ontology through sly subversions of painterly traditions. Still, it’s the Modernists who really upended “la toilette” as we typically recognize it, imbuing the old chestnut with a newfound grandeur and ferocity. Perhaps the most arresting example has to be Picasso’s spin on “la toilette”, which adds a dark, psychosexual spin on a classic.

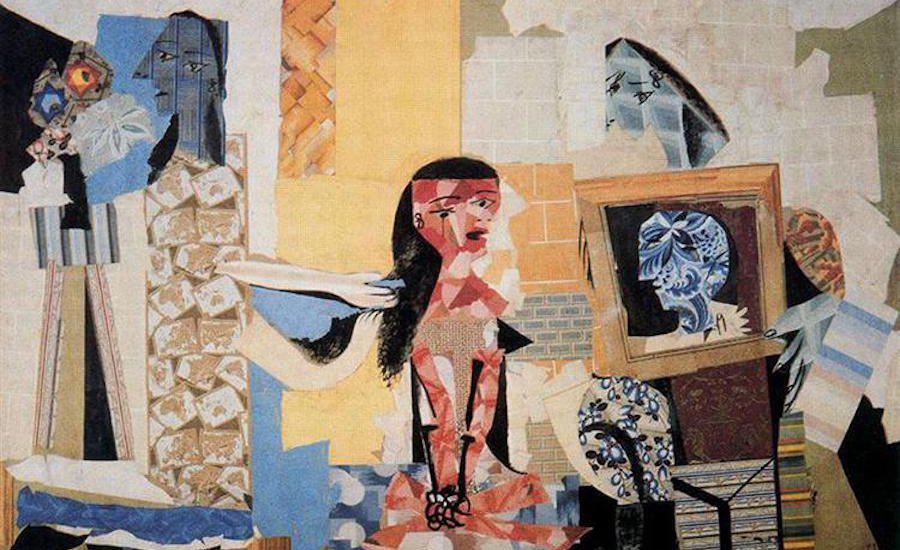

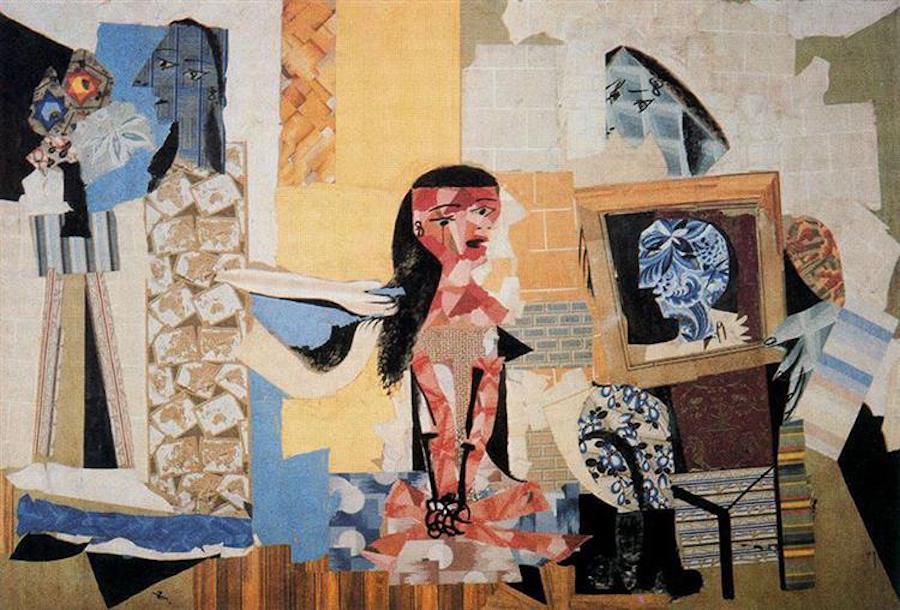

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s upcoming Picasso and Paper exhibition, debuting April 24th, tracks the legendary artist’s development over the course of his career through the prism of drawing and collage, the latter of which Picasso has been credited with inventing as a fine arts discipline. An ode to his astounding prolificacy, the more than 300 works on view will tell the story not just of his craft, but of his relationship to methodology itself. The jewel of the show is a loan from Musée national Picasso-Paris, a 14-foot collage from 1938 entitled "Women at Their Toilette". The piece was completed one year after "Guernica", his most renowned work, was displayed at the World’s Fair in Paris, cementing the artist’s anti-Fascist allegiances during the Spanish Civil War.

"Women at Their Toilette", 1938, via Cleveland Museum of Art

"Women at Their Toilette", 1938, via Cleveland Museum of Art

The sprawling "Women at Their Toilette" features a fairly common motif not just for Picasso, but for art history at large: the artist's voyeuristic gaze eroticizing the domestic interiority of its female subject, often to somewhat academic ends. Three pointy, patterned female figures inhabit a busily-rendered room of ambiguous proportions that appears to be expanding and contracting at the same time. The central woman, whose body is cut raggedly from orange and pink speckled paper, sits cross-legged on the floor, naked, mouth agape. She is flanked by two blue-faced women, one of whom assists her by brushing her hair, the other of whom holds a mirror in which the central figure’s face is reflected back in abstracted shades of swirling cerulean. Intersecting and overlapping planes of yellow, cream, grey and green form a backdrop that appears alive, shedding aspects of itself to reveal endless space beneath. The stillness of his chosen pictorial conceit is undercut by the frenetic violence of his medium, lending an air of entropic anxiety to the piece as a whole. At the time it was made, Picasso was cheating on his mistress, Maria Therese, with young artist Dora Maar; he was still married to Olga, his wife. This stacked duplicity feels present in Women at Their Toilette; the seated figure’s hands look bound at first glance; the blue women seem utterly dispassionate. This busy symphony of twisted limbs and dangerous angles hints at unspeakable tension, a complexity that further animates this torrid, gripping work. Picasso is in control both of this spellbound and the excised women he's created, quite literally, from scratch.

"Women at Their Toilette" is nothing short of a masterpiece, achieving a tableau both emotionally sumptuous and spatially destabilizing in its immediacy. "Guernica" definitely owes its unforgettable, savage kineticism to this collage, as does a not insignificant segment of contemporary figuration itself; countless artists are still making work that looks just like this, and for an eighty-year-old piece, it feels stunningly fresh. Heartache, ecstasy, sexual intrigue, and affectual honesty delivered with haunting panache—that was Picasso’s great gift, the ability to reflect the ebbs and flows of human frailty through expert composition.

"Les Desmoiselles les d'Avignon", 1907, via MoMA

"Les Desmoiselles les d'Avignon", 1907, via MoMA

This is a brilliantly cruel portrait of prurience, a waltz through control, a study in the troubling covetousness of toxic love. To find humanity in the purview of aestheticization is to touch the heartbeat of an audience through affect, and therein lay Picasso’s unique, ferocious genius. "Women at Their Toilette" is more than a sign of its time; it forces us to understand the cost of abstraction, the weight of looking, and the darker side of the human condition.

RELATED STORIES