Art history is a veritable menagerie of mythical and hybrid creatures like the chimera, the dragon, and theunicorn. Gaze upon them in these seven works dating from the ancient to medieval periods, excerpted from the newly revised and updated edition of Phaidon's 30,000 Years of Art.

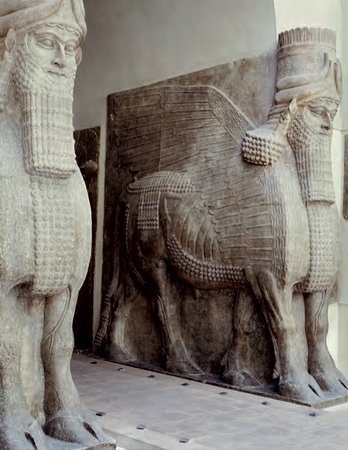

WINGED BULLS

Iraq, Neo-Assyrian Empire, c. 710 BC

Musée du Louvre, Paris

The human-headed winged bulls and lions that stood at the gateways of Neo-Assyrian (c. 911–609 BC) palaces at Nineveh, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu) and Khorsabad (ancient Dur-Sharrukin) are among the most iconic examples of ancient Mesopotamian art.

These bulls come from the palace of Sargon II (r. c.721–705 BC) at Khorsabad. They are larger than their predecessors and modeled in particularly high relief. Great attention has been paid to the elaborate beards and hair, the horned caps marking the figures as divine, and to the feathers of the bulls’ great wings. While they give the impression of sculpture in the round, in fact only the heads are conceived in three dimensions. The presence of a fifth leg in this view shows that to some extent the piece was conceived as two distinct compositions, one to be viewed frontally and one in profile.

Such sculptures are associated with the beginning of major excavations in Iraq, chiefly conducted by Paul-Émile Botta – excavator of these colossal winged bulls from Khorsabad – and by Sir Austen Henry Layard. The recovery of sculptures and reliefs from the palaces of ancient Assyria became a matter of imperial competition between France and England. The figures were celebrated on their arrival in Europe, and, although the decipherment of the cuneiform script was in its infancy, the magical and protective roles of the statues were quickly recognized.

WOUNDED CHIMERA OF AREZZO

Italy, Etruscan, c. 375 BC

Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence

This bronze chimera, from the first half of the fourth century BC, has been famous since its discovery on November 15, 1553, near the Porta San Lorenzo of the Etruscan city of Arezzo. Inscribed on the wax model prior to the casting of the sculpture was a dedication in Etruscan: "gift to Tinia" (Lat: Jupiter); it was surely a votive offering in some sanctuary located just outside the walls of the city. The hollow-cast statue is near life-size, and its pose and wounds (bleeding gashes on the goat’s neck, just visible below the head turned away, and on the lion’s left hind leg) have been taken as evidence that it was part of a group portraying the mythical slaying of the monster by Bellerophon. The letter forms of the inscription are characteristic of northern Etruria, and the sculpture was in all likelihood created by a master in Arezzo.

The lean, naturalistic forms of the smooth body, with muscular legs, bony paws and protruding ribs and veins, contrast with the formalized, intensely textured, flame-like tongues of the long mane. Such stylization of pelt, and the simplified, mask-like face and eyes, are found in Archaic Etruscan works, such as the well-known Capitoline Wolf of Rome (c.480 BC). The Slaying of the Chimera was a popular motif in Etruscan art, and like the Capitoline Wolf, this chimera has inspired artists ever since its discovery. The animal appears in medieval art as a hybrid monster, with human face and serpent tail; later versions often morph into a sphinx-like creature.

MYTHICAL CREATURE

China, Eastern Zhou Dynasty, Warring States Period, c. 300 BC

Shaanxi Provincial History Museum, Xi’an

The oversized, beautifully designed antlers of this remarkable creature exhibit “zoomorphic juncture,” the convention of incorporating smaller animals (here, only their heads) to represent certain details of a larger animal’s body. The practice is extended also to the creature’s snout and tail, which are shaped like raptors’ beaks, and its body is decorated all over with clouds. Similar elements feature on earlier Chinese artifacts, and clearly the deer – if that is what it is – has mythical implications.

The Warring States period (481– 221 BC) figurine comes from an Ordos tomb at Nalin’gaotu, Shenmu County, Shaanxi Province, and may have been made either in one of the central Chinese states or by one of the gold-loving pastoral tribes from Central Asia. Zoomorphic juncture is commonly seen on artworks of the Sarmatians, a nomadic people who occupied the Central Asian steppe lands during the later first millennium BC, and the zoomorphic treatment of some Ordos artifacts may reflect contemporaneous Siberian and Central Asian styles.

The 12 small holes around the edges of its four-petal base suggest that the object may have been part of a leader’s headdress. Its form fits comfortably within the group of ‘cosmic deer’ that appear across Central Asia, notably in Barrow 2 at Pazyryk, where the finial of a staff is shaped like a griffin in a similar pose, and where a well-preserved male body was tattooed with a design almost identical to that on this creature.

WINGED HORSES

Italy, Etruscan, c. 300 BC

Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Tarquinia

The remodeling of the great temple of the Etruscan city of Tarquinia in the Hellenistic period (323–27 BC) incorporated a set of plaques (now restored) depicting the chariot of a beautifully dressed goddess drawn by this remarkable pair of winged horses that date to the end of the fourth century BC or later.

The Tarquinia temple, known by the modern nickname Ara della Regina (Altar of the Queen), would have dominated the view of the city from the south. An inscription suggests that it may have been dedicated to the goddess Artumes (Lat: Diana, Gk: Artemis). Etruscan temples had open gables beneath a tiled roof, with the ends of the massive roof beams shielded from the elements by ornately decorated terracotta plaques, such as this.

The spirited horses are powerfully rendered, prancing and champing at the bit. Their swelling muscles and tendons contrast with the movement of pricked ears, deeply textured manes, and feathered wings. In addition to the highly inefficient collars of draught horses, these steeds wear bulla (bubble) amulets attached to their bridles, a custom common for pets throughout Italy; children often wore similar amulets.

Because of their position near the temple roof, the relief of the horses’ heads is much deeper than that of their feet. They seem to lean out towards the viewer, but optical perspective would have made them look quite natural when high on the temple gable.

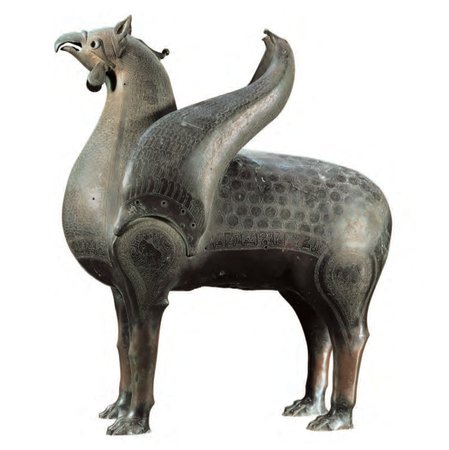

PISA GRIFFIN

Spain, Medieval Period, c. 1050

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Pisa

This extraordinary sculpture is one of the great puzzles of Islamic art. It is the largest and most beautiful of a group of animal sculptures probably dating to the eleventh century and fashioned of copper alloy in the shape of griffins, stags, gazelles, lions, rabbits, eagles, and other birds. They all share a high degree of stylization and all-encompassing decoration. This griffin, for example, is engraved with panels of vegetal, geometric, and epigraphic ornament, including an inscription band invoking many good wishes on its owner.

Most pieces were functional, used as aquamaniles (ewers, water jugs for washing), incense burners, fountain spouts, padlocks, and possibly vessel supports. The purpose of this sculpture is unclear; the latest suggestion is that it is a giant noisemaker that emulates a roaring lion. Its provenance is equally murky: since the late 1400s it adorned the cathedral of Pisa, but attributions of its origin have ranged from Iran to Spain, Egypt, North Africa, and Sicily. Spain seems its most likely origin, although how it arrived in Pisa remains a mystery. Its imposing size and monumentality exemplify the wilful abstraction typical of medieval Islamic art, in which realistic figures of animals and people are dematerialized so that they skirt the edges of orthodox Islamic propriety.

DAVID VASES

China, Yuan Dynasty, 1351

Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, London

Below the collar on the neck of each of this pair of vases is an inscription 61 characters long. It records their presentation by one Zhang to a temple near Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, in 1351, a date that puts them among the earliest extant examples of fine blue-and-white Chinese porcelain. The vases, of white porcelain with underglaze decoration in cobalt blue, are superb in shape and proportion. Each has two elephant handles, from which rings originally hung, and a hollow foot. The decoration on each is complex and almost, though not quite, identical. On the rim, shoulder and around the upper foot, three bands are painted with floral arabesques of chrysanthemums, lotus and peonies respectively. The inscriptions are set among plantain leaves, and phoenixes fly around the lower neck. A dragon writhes about the body of each vase, and round the base are a series of panels containing auspicious symbols.

The origins of this famous ceramic form are uncertain, though the David Vases (so-called because they were collected by Sir Percival David) must represent an already mature stage in its development. Cobalt first reached China under the Mongol regime, and blue-and-white porcelain from the great Jingdezhen kilns was exported to the Middle East, where it was much appreciated: Istanbul’s Topkapi Museum now owns a superb collection.

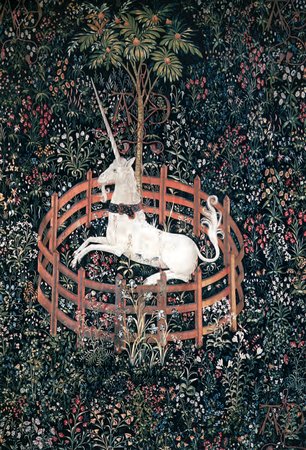

UNICORN IN CAPTIVITY

Netherlands, International Gothic Style, c. 1500

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Tapestries were the most highly prized and expensive form of decoration in the Middle Ages.

A panel like this would have taken a team of four to six male weavers at least a year to complete. Although produced in the southern Netherlands, the series of seven Unicorn Tapestries, dated to c. 1495–1505, was probably based upon Parisian designs. They depict the hunt for the elusive unicorn, but the narrative can be allegorically interpreted as both the story of Christ and a tale of courtly love.

The symbolism suggests that the tapestries were intended to celebrate the marriage of a noble lady, whose initials, A E, are entwined in the tree seen here. This final scene, following the capture and killing of the mythical beast, shows the reanimated unicorn chained and fenced in a super-abundant meadow. The noble beast symbolizes both the Resurrection of Christ and the capture of the lover-bridegroom. The pomegranate fruit, which drips blood-like juice on the unicorn’s side, reiterates the Resurrection but also represents the unity of the Church and refers to chastity. There are over 100 plant species depicted in the cycle, and this panel contains at least 20, which make countless allusions to love, fidelity, marriage and fertility.