Although artists have been making magazines at least since the late 18th century, the artists' magazine took on a new significance in the 1960s. During that experimental decade, artists began to use the format of the magazine to question the very nature of art. The ephemerality, immediacy, and popular nature of magazines appealed to a generation of artists that challenged the exalted status of painting and sculpture. The magazine's highly mobile form also piqued the interest of artists who were frustrated with the limited distribution networks of the mainstream gallery system. As seen in the examples below, artists saw magazines as site of experimentation and inspiration.

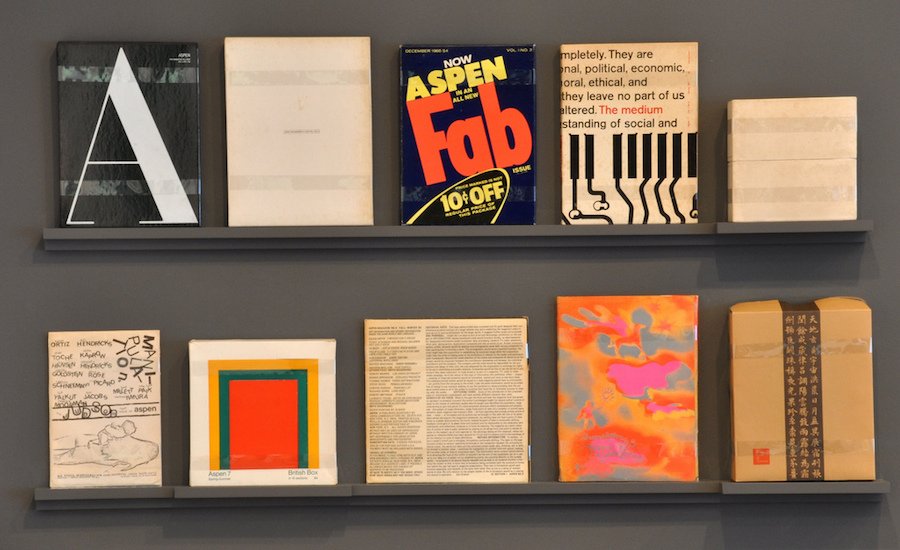

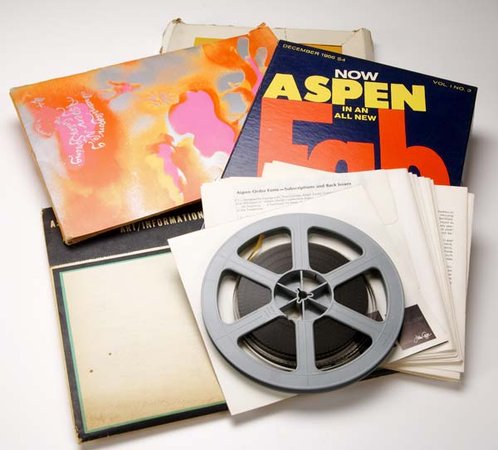

ASPEN

(1965-1971)

Image courtesy of projectspace.ca

Image courtesy of projectspace.ca

Phyllis Johnson, a former editor for Women’s Wear Daily and Advertising Age, founded Aspen: The Magazine in a Box in 1965. Seeking to capture the holistic cultural diversity she saw in Aspen, Colorado, Johnson abandoned the format of the bound magazine in favor of a multimedia approach that wasn't restricted to the printed page. Issues frequently featured music, film, and art. The artist Brian O'Doherty edited what is perhaps the most well known issue of Aspen, a dual issue dedicated to minimalism and conceptual art. Taking the multimedia mandate of the magazine to its most extreme, the issue featured phonograph recordings by Marcel Duchamp and John Cage; a model Minimalist maze by Tony Smith; super-8 films by Robert Rauschenberg and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy; and text works by Mel Bochner and Sol LeWitt. Although its innovative format ultimately proved unsustainable (the magazine folded after just 10 issues), Aspen is still regarded as one of the most innovative publications of its time.

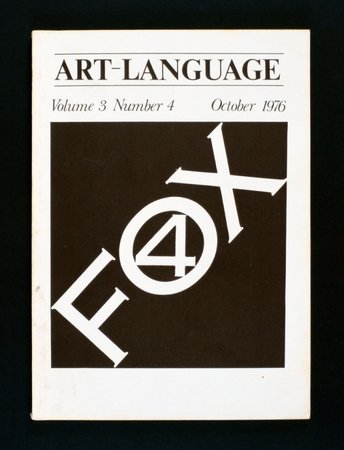

ART-LANGUAGE

(1969-1985)

Image courtesy of moussemagazine.it

Image courtesy of moussemagazine.it

Published intermittently by the British artist group Art & Language (whose members at the time were Michael Baldwin, David Bainbridge, Terry Atkinson and Harold Hurrell), Art-Language was a forum for the then-nascent movement of Conceptual Art. While the magazine was not a work of art per se, artists such as Dan Graham, Lawrence Weiner, and Sol LeWitt published texts that, in keeping with their larger conceptual practices, blurred the boundaries between language and art. LeWitt's seminal “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” for instance, was published in the first issue of Art-Language in 1969. Nonetheless, Art-Language did not purport to definitively represent or determine the terms of conceptual art practice; its original subtitle, "The Journal of Conceptual Art," was removed after the first issue. The magazine's embrace of conflict and dissent makes it a rich primary source, one that paints a more nuanced, and perhaps more accurate, portrait of a movement which is often seen today as a unified whole.

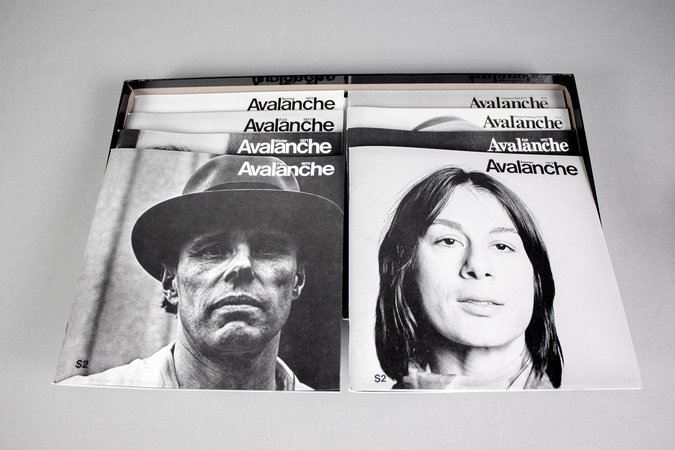

AVALANCHE

(1970-1976)

Image courtesy of theartofprinting.org

Image courtesy of theartofprinting.org

When magazine editor Liza Béar and independent curator Willoughby Sharp founded Avalanche magazine in 1970, their goal was create a space for artists’ voices and ideas. To that end, Avalanche did not feature criticism and reviews. Instead, it published interviews and documentation—primary sources that privileged the artist over critics. Béar and Sharp used photography extensively, turning the pages of their magazine into a quasi-exhibition space. This almost institutional function of the magazine was an important one, considering that many of the artists featured in Avalanche were working in mediums that either openly defied or were not yet seen as fit for more traditional art spaces. The magazine's first issue, devoted to Earth Art, featured Joseph Beuys on the cover and included interviews with Carl Andre and Jan Dibbets and a roundtable discussion with Michael Heizer, Robert Smithson, and Dennis Oppenheim. Later issues featured contributions from Vito Acconci, Walter De Maria, Philip Glass, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, Gordon Matta-Clark, Bruce Nauman, Yvonne Rainer, Richard Serra, William Wegman, Lawrence Weiner, and Jackie Winsor.

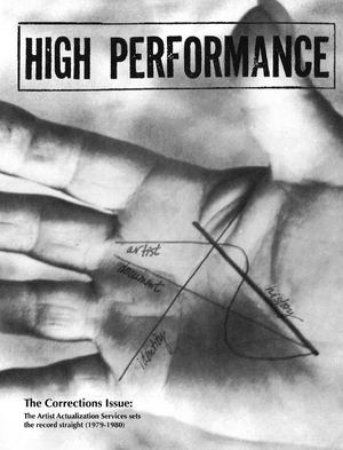

HIGH PERFORMANCE

(1978-1997)

Image courtesy of latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster

Image courtesy of latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster

A quarterly magazine based in California, High Performance was the first magazine devoted exclusively to Performance Art. The goals of the magazine were to define a movement that was still seen as derivative of music, theatre, and dance, and to create a body of knowledge and discourse that would help to legitimize it. The magazine's content was a combination of documentation and artists’ statements, which preserved an art form that was often either ephemeral or site specific. High Performance, likeAvalanche, privileged the voice of the artists, a gesture that was particularly important given the skepticism (if not outright hostility) of critical responses to performance at that time. High Performance also did much to distinguish California-based performance from its counterpart on the East Coast. Prominent West Coast contributors included Chris Burden, Paul McCarthy, and Mike Kelley.

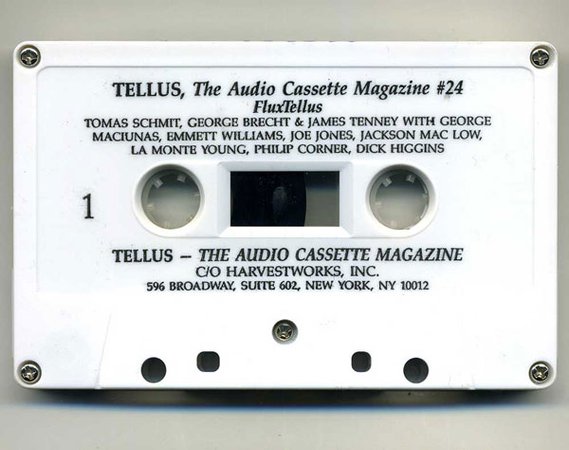

TELLUS

(1983-1993)

Image courtesy of arttattler.com

Image courtesy of arttattler.com

As a magazine that was distributed in the form of cassette tapes, Tellus might seem like a rejection of print. But although its main goal was to legitimize the cassette, it exploited the circulation and other properties of magazines. The editors hoped that Tellus would help to extend experimental music and sound beyond the insular mechanisms of mail order and personal exchange, and in this regard the print magazine was an important precedent. Tellus published experimental and no-wave music, sound poetry, and audio and sound art. Its issues were organized thematically around topics such as "Music with Memory," "The Sound of Radio," "The Improvisers," "Video Art Music," and "Experimental Theater." The magazine featured art by Kiki Smith, Richard Prince, Mike Kelly, David Wojnarowicz, and Joan Jonas, and published what are now canonical sound works by Louise Lawler (Birdcalls) and Christian Marclay (Groove).

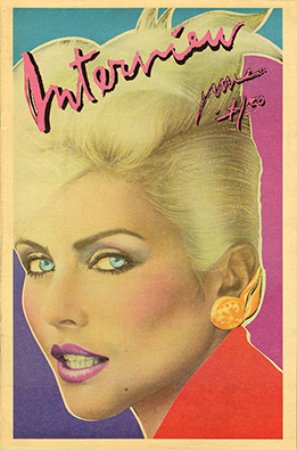

INTERVIEW

(1969-)

Image courtesy of carnegiemuseums.org

Image courtesy of carnegiemuseums.org

Interview is a rare example of an early artists’ magazine that is still published today. The magazine was started by Andy Warhol and longtime collaborator David Dalton after the two edited the third issue of Aspen. Inspired by Rolling Stone, which was then a chronicle of counterculture music, Warhol saw Interview as a voice for alternative film. As its title suggests, Interview privileged the question-and-answer session, although the magazine didn't necessarily revere this organizing principle; it wasn't uncommon for a contributor to preface an interview with distaste for the format, or for Warhol himself to interrupt a conversation and derail it. Warhol's larger practice consistently courted the commercial, and so did Interview. The magazine's enduring success is a testament to its commercial viability, something that sets Interview apart from many other artists' magazines that were often too experimental to garner sustaining financial support.