It's looking like institutions finally got the message: the time to diversify the canon is long overdue. "Lygia Pape: A Multitude of Forms" on the female Brazilian artist just opened at the Met Breur; "Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction " opens April 15th at MoMA; and "We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85"opens at the Brooklyn Museum on April 21st.

"We Wanted a Revolution" focuses on the work of black women artists during the emergence of second-wave feminism—a primarily white, middle-class movement ( Judy Chicago 's The Dinner Party might ring a bell). What we forget is that just as Chicago and Miriam Schapiro (co-founders of the Cal Arts Feminist Art Program) opened Womenhouse , a 1972 site-specific work in a Los Angeles house, artists like Betye Saar and Senga Nengudi were also engaging in discussions of black female subjectivity and oppression.

Following the debates about the need for intersectional feminism following the Women's March in February, the upcoming Brooklyn Museum exhibition is timelier than ever. In this excerpt from Phaidon's Art and Feminism , we examine six radical black feminist artists to know before you see "We Wanted a Revolution."

...

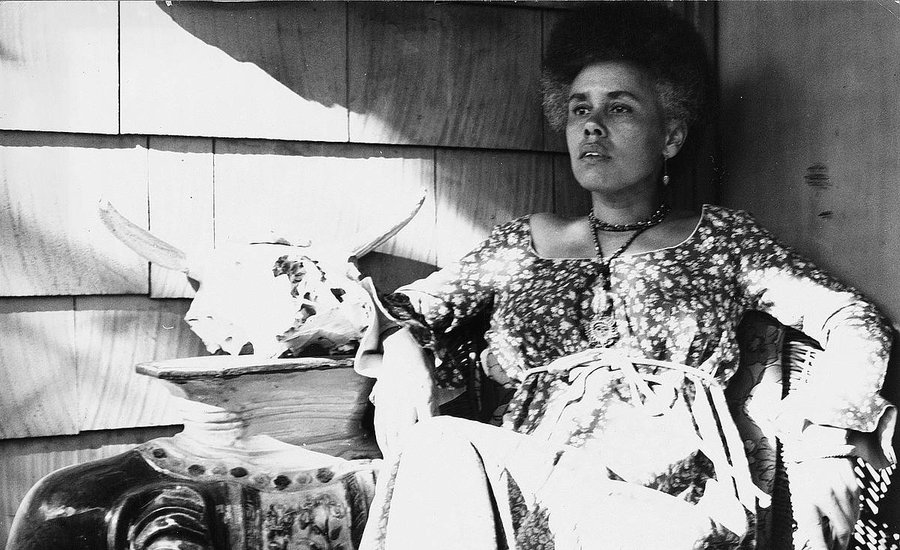

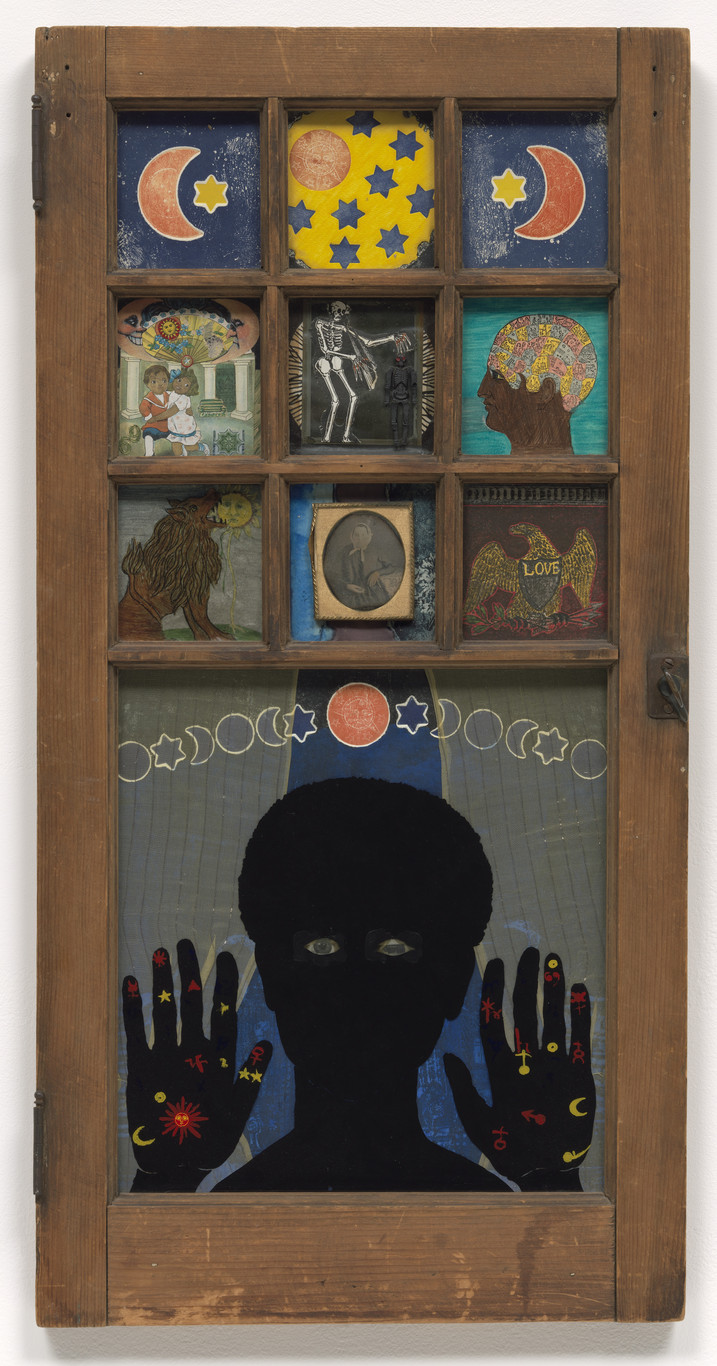

Betye Saar,

Black Girl's Window

, 1969

Betye Saar,

Black Girl's Window

, 1969

“I knew it was autobiographical…there’s a black figure pressing its face against the glass, like a shadow. And two hands that represent my own fate….Death is at the centre. Everything revolves around death. In the bottom is a tintype of a woman. It’s no one I know, just something I found. My mother’s mother was white. Irish. And very beautiful. I have a photograph of her in a hat covered in roses. And there’s the same mix on my father’s side. I feel that duality, the black and white." -Betye Saar. Artist’s Stament, 1984

Saar began making assemblage works in the late 1960s. She used assemblage not only because it challenged fine art categories in its use of found and recycled materials but because it enabled her to work with concentrated layers of symbolism.

Saar first explored autobiography in Black Girl’s Window . In this work Saar adds a further dimension to her use of assemblage: it becomes a ritual process. Symbols derived from occult sources suggest that the trapped figure needs to connect with the spiritual in order to escape from her confines.

Betye Saar's

A Handful of Stars

, 2016 is available here on Artspace

Betye Saar's

A Handful of Stars

, 2016 is available here on Artspace

ADRIAN PIPER

Adrian Piper,

Catalysis III

, 1970-1, New York

Adrian Piper,

Catalysis III

, 1970-1, New York

Piper’s performance, which took place in the street, on the subway, in museums, bookshops and other public places, demonstrate a desire to question and disrupt gender social attitudes towards difference, and how it is read through a person’s appearance and gestures. In her Catalysis series her presence, or “quirky personal activities,” were genuinely disruptive. For example, she would appear on the subway in stinking clothes during rush hour or with balloons attached to her ears, nose, hair and teeth. She would go shopping in a smart department store in clothing with sticky paint letters reading ‘WET PAINT’ or to a library carrying concealed tape recording of loud belches. In this way she forced a direct confrontation with the public. In the Mythic Being series Piper disguised herself as an androgynous racially indeterminate young man, wearing a black t-shirt, flared jeans, big sunglasses, an afro-wig and Zapata-style moustache.

Adrian Piper, Still from

Mythic Being

, 1973

Adrian Piper, Still from

Mythic Being

, 1973

H OWARDENA PINDELL

Howardena Pindell, still from

Free, White and 21

, 1980

Howardena Pindell, still from

Free, White and 21

, 1980

This piece is a video self-portrait that recounts several of Pindell’s experience as an African-American woman growing up in the United States. It recounts her childhood experience of being cared for by a white babysitter; her experiences in kindergarten, as a student in high school; in university; receiving a job rejection; and finally being treated badly at a weeding, as the only black woman present. During these accounts a white woman interjects with: “you don’t exist until we validate you”: “and you know, if you don’t want to do what we tell you then we will find other tokens”; and finally: “and you must be really paranoid. I have never had experiences like that. But, of course, I am free, white and twenty-one.” The work directly criticizes white feminist and racism prevalent within the art world. Pindell worked with the Heresies collective and other feminist groups. This video was first shown in the exhibition “Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists in the United States” in September 1980 at AIR Gallery, New York, curated by the artist Ana Mendieta.

Carrie Mae Weems,

Mirroir, Mirroir,

1987-88

Carrie Mae Weems,

Mirroir, Mirroir,

1987-88

Weems has worked since the mid 1980s with visual and verbal narratives that address African-American experience of racial and gender stereotyping and oppression. She offers possible strategies for black women’s self-recovery, through the engagement of various levels of reading of African-American cultural forms such as folklore, as well as representations from white culture. Weems combines and subverts the cultural expectations of viewers approaching the work from various perspectives, using tableaux, narratives, ironic and sardonically humorous images and texts. Prejudice based on skin color is addressed directly in Mirror, Mirror part of the Ain’t Jokin series. The work ironically rebounds upon and thus renders impotent the genre of the racist joke. At the same time, Mirror, Mirror communicates dilemmas of identification for both black and white women who encounter the work, inviting each to question the notions of beauty in which they situate themselves.

Carrie Mae Weem's

Nikki's Place

(from the Roaming Series), 2005-06 is available here on Artspace

Carrie Mae Weem's

Nikki's Place

(from the Roaming Series), 2005-06 is available here on Artspace

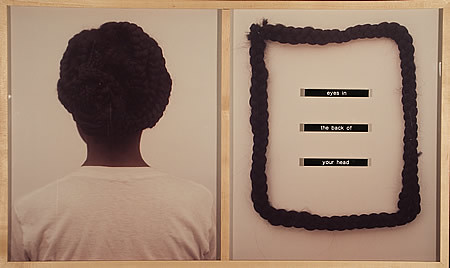

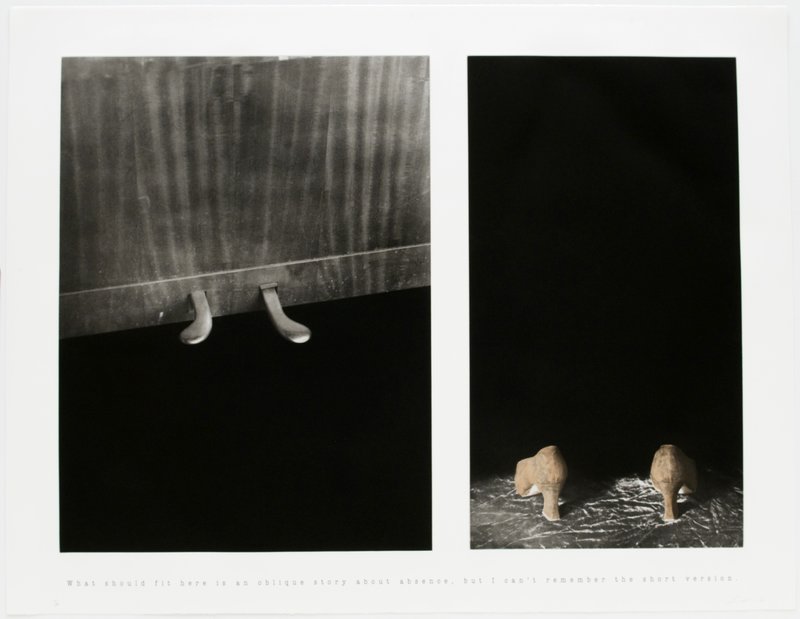

Lorna Simpson,

Back (Eyes in the Back of Your Head)

, 1991

Lorna Simpson,

Back (Eyes in the Back of Your Head)

, 1991

This is one of a series in which Simpson has assembled fragmented Polaroid images of a female model whom she has regularly collaborated with: at other times, in a work such as

Guarded Condition

(1989) Simpson has used images of her own body. In both cases, the body is fragmented and viewed from behind. The back of the mdoel’s head is sensed as being in a state of guardedness towards possible hostility she can anticipate as a result of the combination of her gender and color of her skin. In this image the complex historical and symbolic associations of African-American hairstyles are also brought into play. The message of the text and formal treatment of the image reinforce a sense of vulnerability. The fragmentation and serialization of bodily images disrupts and denies the body’s wholeness and individuality. In attempting to read the work the viewer is provoked into confronting recent histories of Western appropriation and consumption of the black female body.

Lorna Simpson's

Untitled

, 1991 is available here on Artspace

Lorna Simpson's

Untitled

, 1991 is available here on Artspace

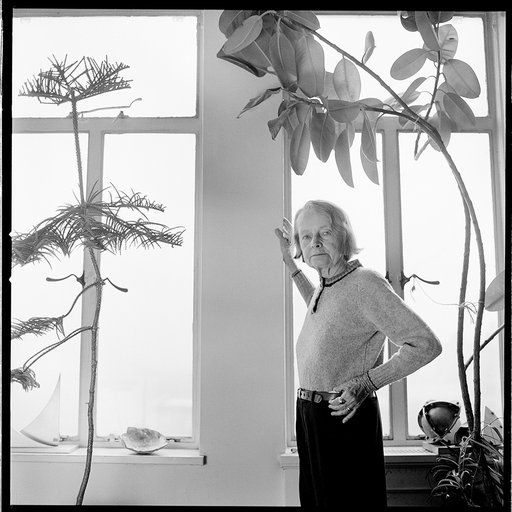

LUBAINA HIMID

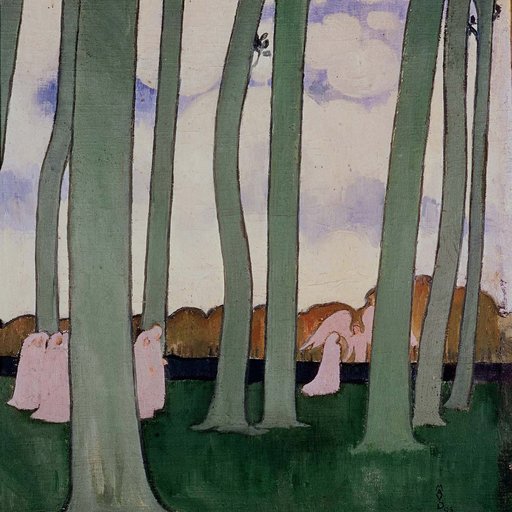

Lubaina Himid,

We Will Be

, 1983

Lubaina Himid,

We Will Be

, 1983

British artist Himid was born in 1954 on the African island of Zanzibar, then still a British colony, now part of the independent republic of Tanzania. Himid’s work excavates repressed and forgotten histories of the experiences and cultures of people of African descent. She brings these histories into contemporary contexts where white social and historical hierarchies are questioned and challenged. Her figures often evoke the Bubain physiognomies and cultural forms of the Egyptians whose civilization was absorbed into classical Greek culture—an African influence that was gradually denied and written out of European history from the early period of the European slave trade until the late twentieth century. Important to her work is painting’s intersection with decoration and adornment in the everyday life of cultures which have been marginalized. Himid also draws on the tradition of history painting, depicting moments where black women are visible in history and are active in determining its course.

Detail from Kara Walker's

Camptown Ladies,

1998

Detail from Kara Walker's

Camptown Ladies,

1998

Walker uses black-paper silhouette cut-outs to construct imagery that mingles “the most deeply disturbed fantasies of Southern whites with the hitherto unimaginable visions of a contemporary young African-American woman…these scenes, at first glance the offspring of countless moonlight-and-magnolias illustrations, invariably turned out on closer inspect to involve blatantly coarse seductions or horrifically perverse scenarios.”- Jerry Cullum, “Landscape, Borders and Boundaries,” 1995

The work sparked controversy, going beyond a clearly positioned critique of historically racist imagery to explore a seductive fascination with repressed and forbidden layers of interpretation.

Kara Walker's

Untitled Pitcher

is available here on Artspace

Kara Walker's

Untitled Pitcher

is available here on Artspace

[related-works-module]