Installation art has flowered in the early years of the 21st century, with increasingly ambitious projects popping up in museums, galleries, and beyond. These seven works, excerpted from Phaidon’sThe Twenty-First Century Art Book, represent just a few of the most affecting ways contemporary artists have physicalized their concepts to create interactive experiences that tug at the boundaries of art making.

UNTITLED

Monika Sosnowska

2002

Sosnowska’s installations and sculptures reproduce the emotional and psychological effects of architecture, particularly the type of institutional buildings that the artist experienced growing up in 1970s and 80s communist Poland. Untitled was a succession of identical, life-sized (though each only around four square meters) rooms, installed as a site-specific, temporary installation. In every adjoining wall was an identical door, each of which led to an identical room with further identical doors. Viewers moving from one room to the next quickly became disoriented, even though there were only nine rooms in total. While the specific purpose of such claustrophobia-inducing architecture was never revealed, the dull green paint applied to the lower halves of the walls is common to hospitals and bureaucratic institutions the world over. In this work and in later, labyrinthine installations such as Loop (2007), Sosnowska recreates the kind of uncanny but banal in-between places that Franz Kafka famously evoked in his novels.

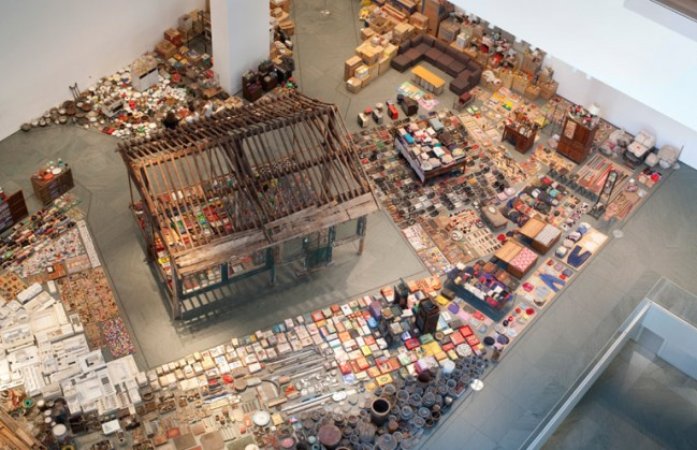

WASTE NOT

Song Dong

2005

Thousands of everyday objects are displayed in the gallery space, ordered neatly in piles according to likeness. The items belonged to the artist’s mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, who collected them over five decades. If our possessions tell the stories of our lives, this installation speaks of both thrift and obsession. Old pieces of soap are displayed alongside countless plastic bags, neatly folded, as well as more personal items such as shoes, toys, and linen. Song began the work after the sudden death of his father in 2002, to try and cope with the family’s grief and the installation features a neon sign displaying the message, “Dad, don’t worry, Mum and all the family are well.” As well as exploring his relationship with his family, Song’s art examines life in modern China: the installation reflects the changes the family experienced during his mother’s lifetime, which included periods of extreme poverty. The work became a poignant memorial when the artist’s mother died in 2008.

CHIZHEVSKY LESSONS

Micol Assaël

2007

Suspended rows of copper plates surround an adapted power generator so that the whole room is transformed into an electrostatic field. Electrostatic phenomena can be experienced when, for instance, we rub synthetic cloth against a balloon and a charge is created by friction. This build-up can be discharged by bringing the surface into contact with a non-conductive surface, and is sometimes experienced as a mild “shock.” The air around Assaël’s Chizhevsky Lessons becomes tangibly charged and visitors are warned not to touch each other’s faces. The artist produced the work in cooperation with a physics research institute in Moscow and drew on the investigations of Alexander Chizhevsky who studied the impact of electrostatic fields on the human psyche. Assaël, who was the Future Generation Art Prize 2012 Special Prize Winner, often uses obsolete scientific apparatus in her work to explore scientific and physical phenomena and their interaction with the human body.

SEIZURE

Roger Hiorns

2008

In his installation Seizure, Hiorns covered the walls and ceiling of a condemned council flat in Southwark, south London, with a thick layer of bright blue crystals. The effect was produced by pumping 75,000 liters of liquid copper sulfate into the property, which then formed a crystalline growth on all available surfaces, including the bath. Visitors could enter the flat and walk around the exotic interior, which was both beautiful and threatening. In 2011 the block housing Seizure was due for demolition, but after being acquired by the Arts Council Collection the 31-ton installation was extracted and moved to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, near Wakefield, where it is now displayed. Hiorns regularly creates transformative effects on objects or spaces, also working with unusual substances such as brain matter and fire. By using reactive materials, Hiorns invites an element of chance into his art.

HOW IT IS

Miroslaw Balka

2009

Appearing like an enormous shipping container, this imposing steel structure dominated the Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern. Raised up on 2-meter-high stilts and accessed via a ramp at one end, visitors were invited to enter its pitch-black interior. Many found the experience of negotiating the cavernous chamber to be unnerving and bewildering. With a total absence of internal light, the work provokes feelings of apprehension, foreboding and, upon leaving, a sense of relief. Much of Balka’s work is concerned with the fate of the Jews in his native Poland during the Second World War, the majority of whom were exterminated by the Nazis. This temporary piece alluded to that history, evoking the freight trains that transported victims to concentration camps such as Auschwitz. Known primarily for his non-figurative sculptures using ordinary industrial materials, Balka also works with drawing and video to explore themes of history and memory.

UNTITLED: HOARDINGS

Phyllida Barlow

2012

Reaching up from the floor, Barlow’s enormous scaffold-like sculpture dominates the display space. The complex work consists of numerous vertical and horizontal wooden poles that have been roughly joined together with cement and fabric, evoking something that might be seen on a construction site. Barlow’s apparently slipshod assemblage, as with much of her work, takes its inspiration from the urban environment. She has made work since the 1970s, alongside a career as a celebrated art tutor, and is best known for her large-scale sculptures using cheap, readily available materials such as plywood, plaster, cement, fabric, paper, and cardboard. She assembles them intuitively, often in situ, by throwing, pouring, stretching, and balancing their component parts to create unexpected formal relationships that often respond to their surrounding architecture. The results are abstract, resolutely anti-monumental, and many are crudely colored with industrial paint. Reflecting the transience of life, the fragile sculptures are typically dismantled after they have been shown.

LAST SUPPER (AFTER LEONARDO)

Yinka

Shonibare

2013

The British-Nigerian artist Shonibare has been poking fun at misguided notions of Britishness since his early installations such as Gainsborough’s Mr. and Mrs. Andrews Without Their Heads (1998). In that work, Shonibare paid homage to Thomas Gainsborough’s famous portrait, replacing the couple with headless mannequins and tailoring new outfits from colorful “African-style” batik fabric purchased at London’s Brixton market. (The artist is interested in the fact that the fabric is actually based on Indonesian designs and made in the Netherlands.) Shonibare’s playful critique of post-colonial hybridity has continued through photographic tableaux, in which he himself poses as iconic literary and historic figures. Last Supper (after Leonardo) is one of his most ambitious installations to date, based on Leonardo da Vinci’s fresco but with a goat-hoofed Bacchus – the Roman god of wine – in place of Christ. Around him, mannequins dressed in Shonibare’s signature Afro-Victorian outfits indulge in gluttony and fornication.